The Scottish Government is consulting[1] on Masterplan Consent Area regulations that would bring forward a new form of planning ‘authorisation’, intended to place local authorities at the forefront of design and delivery of a scheme. The current consultation relates to proposed regulations on the procedures to prepare Masterplan Consent Areas (MCAs). It sets out the proposed procedures and includes two sets of regulations: those covering the main process for making MCA schemes and those relating to environmental impact assessments.

MCAs in the planning system

The consultation proposes that MCAs will function alongside Simplified Planning Zones (SPZs). SPZs have been used for a range of development types, including town centre retail, commercial projects, small-scale housing developments. However, the take-up of SPZs has been relatively low. The Scottish Government has said that whilst similar to SPZs, MCAs will be:

“refreshed and rebranded with expanded powers” […]. “MCAs will be broader in scope, being able to give other types of authorisations than just planning permission, and the procedures for preparing a scheme have been modernised.”

It would appear that MCAs are designed to be used on a wider range of site sizes than what has been seen so far in SPZs. The consultation document says:

“A MCA approach could be used by the planning authority to coordinate development, including on large sites, where there may be different land owners. MCAs could support a range of scales and types of development, from small scale changes up to new major or national developments.”

MCAs are flexible in that they can have varying levels of control over the development process. Whilst designed to support the delivery of the development plan, they are not part of it. New schedule 5A of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 will stipulate that local planning authorities must consider creating MCAs at least every 5 years.

“Authorisation” given through a MCA

Section 54B of the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019 (which, once commenced, will enable Masterplan Consent Areas), says that an MCA acts as not just as a grant of planning permission for development, but an “authorisation” for the development as a whole. Such authorisation, as defined in the Act, can comprise the grant of planning permission, as well as other types of consent including listed building consent and road construction.

The intention of this is that it gives a local authority the power to provide coordinated authorisations to development projects. One particular benefit of this is believed to be the ability to present communities with entire schemes for consultation, preventing “consultation fatigue”. The ability to grant holistic authorisation could also arguably reduce some of the administrative processes that can take a long period of time on larger master-planned schemes.

Once the MCA has been agreed, the authorisation can be subject to any conditions, limitations and exceptions specified as specified in the self-issued decision-notice. Notably, MCAs do not have the power to limit any permitted development rights, a factor that will have to be considered in the scheme’s overall design.

Procedures for preparing a MCA

As part of summarising the MCA process, the consultation document says MCAs will serve to “align efforts” and create a “new way of working: planners plan, developers develop”.

The need for strong collaboration, within and across authorities, throughout the MCA process is noted. While working with developers is an option for MCA schemes, the consultation document, the proposed regulations, and other supporting legislation are clear that planning authorities are responsible for the creation and coordination of MCAs, through to delivery.

“Planning authorities may […] wish to work closely with potential developers and investors to understand market aspirations and aspects around feasibility. In some cases, a partnership approach could be taken forward with a development partner(s) who may provide resources to carry out some of the work for example around site investigations or master planning and design.”

Whilst mention of the development sector is encouraging, it is clear that in order for MCAs to come forward effectively, LPAs must push them forward and be proactive in how they engage with developers, designers, constituents, and others, to ensure that proposals proceed successfully.

Resourcing – recouping costs of frontloading

Resourcing implications are considered in more detail in a sister consultation

Investing in Planning: a consultation on resourcing Scotland’s planning system, which is analysed in

this Lichfields blog.

The Investing in Planning consultation notes, regarding MCAs more broadly:

“Regulations and guidance on masterplan consent areas will assist authorities to front-load scrutiny and alignment of consents providing scope for developers to come forward with greater certainty of consent allowing them to raise necessary finance and get on site earlier.”

The MCA consultation notes regarding fees:

“We are aware of previous concerns over resources required for planning authorities to set up SPZs (the predecessor to MCAs) and a loss of planning application fees. We are also very mindful of the current pressures on planning authority resources”.

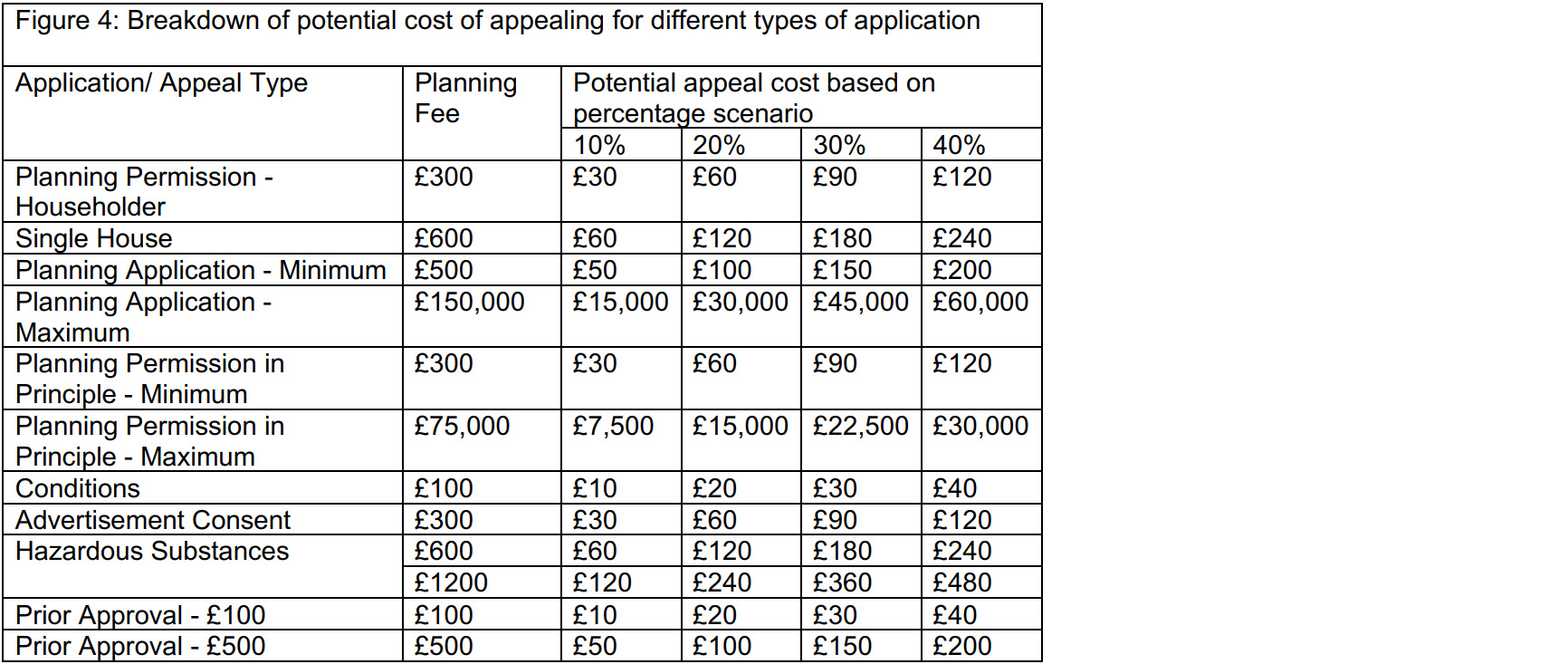

Accordingly, the Investing in Planning consultation proposes that fees and charges for developing within an MCA be set should be set out in the scheme for that MCA, which would include the methodology of how such costs will be apportioned.

Where and why?

The extent to which MCAs will be used across Scotland is dependent on a range of factors. MCAs could be a powerful tool for LPAs to encourage investment in a form that it has control over, and which addresses local policy priorities; MCAs constitue a front-loaded process which place the onus on LPAs to drive their production. However, without buy-in from developers and other key stakeholders, the upfront cost to LPAs associated with the production of a MCA risks not being recouped.

One area where this buy-in could be achieved from a range of stakeholders is on large, complex sites which may have stalled. It may be in cases like this that the ability to grant blanket ‘authorisation’ on a range of works, through MCAs, could provide local authorities and developers alike with the ability to unlock schemes. As an increasing number of councils in Scotland declare a housing emergency

[2], they may see MCAs as being one method to help deliver the homes secure the and investment they need.

The consultation closes on 22nd May 2024.

[1] Masterplan Consent Areas - draft regulations: consultation

[2] STV.