Patterns of development

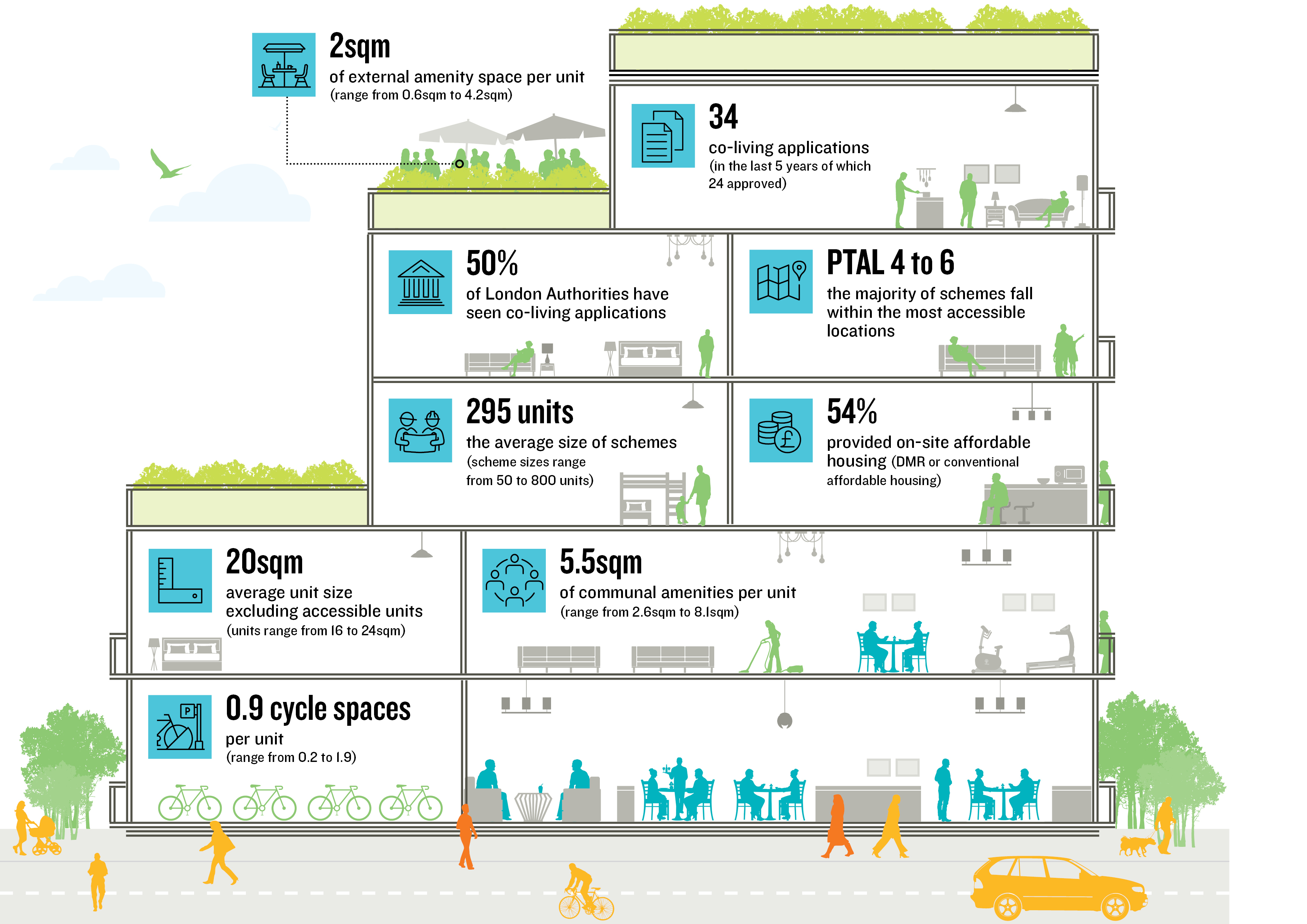

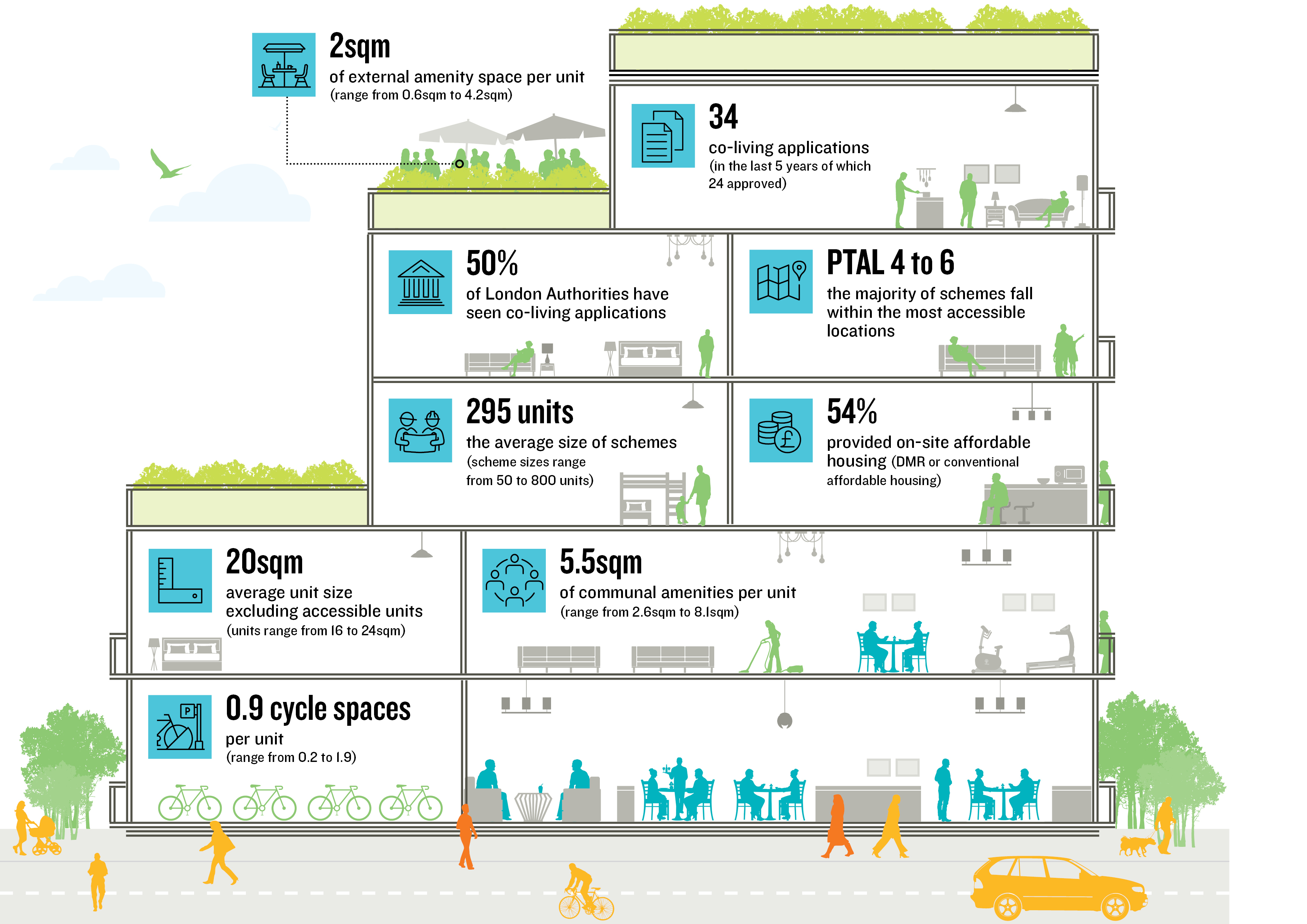

Our analysis of co-living developments in London revealed the following headlines:

Number of Applications

Lichfields has reviewed all planning applications for co-living submitted in the last six years (January 2018 to June 2024). This research focuses on bespoke sui generis co-living schemes. We are aware that there are a number of co-living schemes which operate under a C1 Use Class. However, for the purpose of this research we have focused on those that align with London Plan Policy H16 and the LPG. These are applications which have been submitted following publication of the draft version of the latest London Plan.

This research identifies 34 applications, of which 24 have been approved, 3 refused and 7 are still to be determined. Many of these schemes included other uses, particularly at the ground floor. Other uses typically comprise commercial space including offices, retail food and beverage which compliments the co-living use.

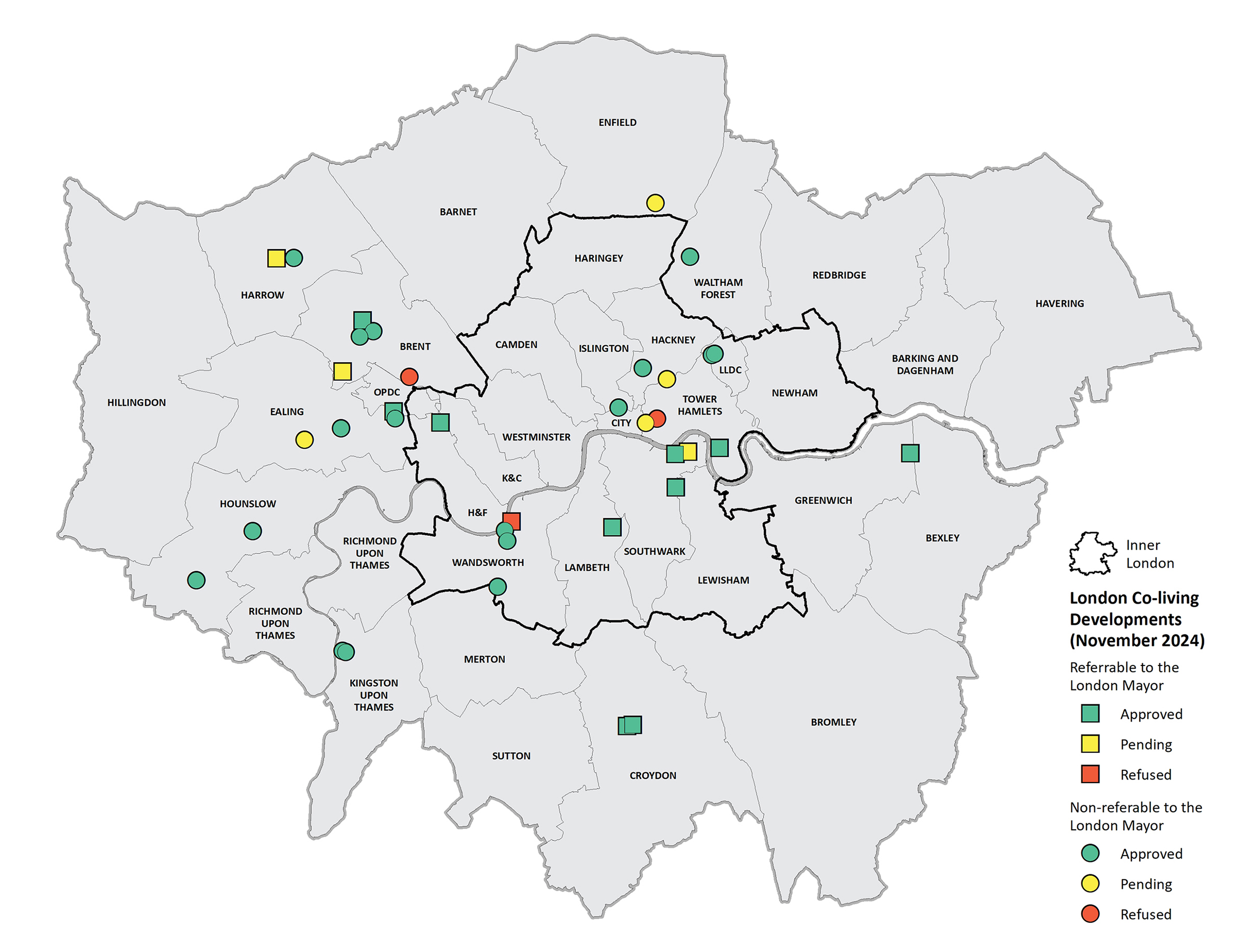

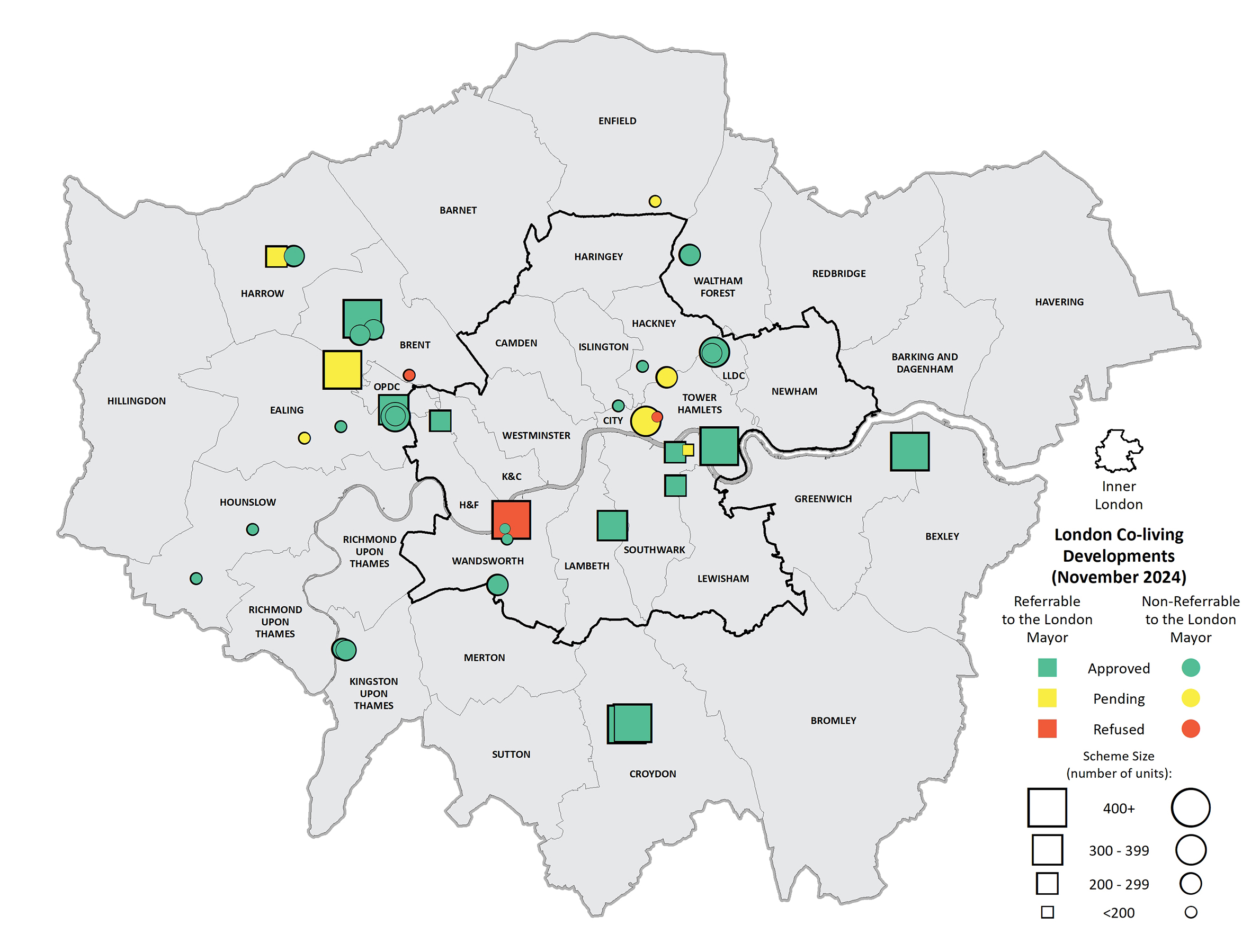

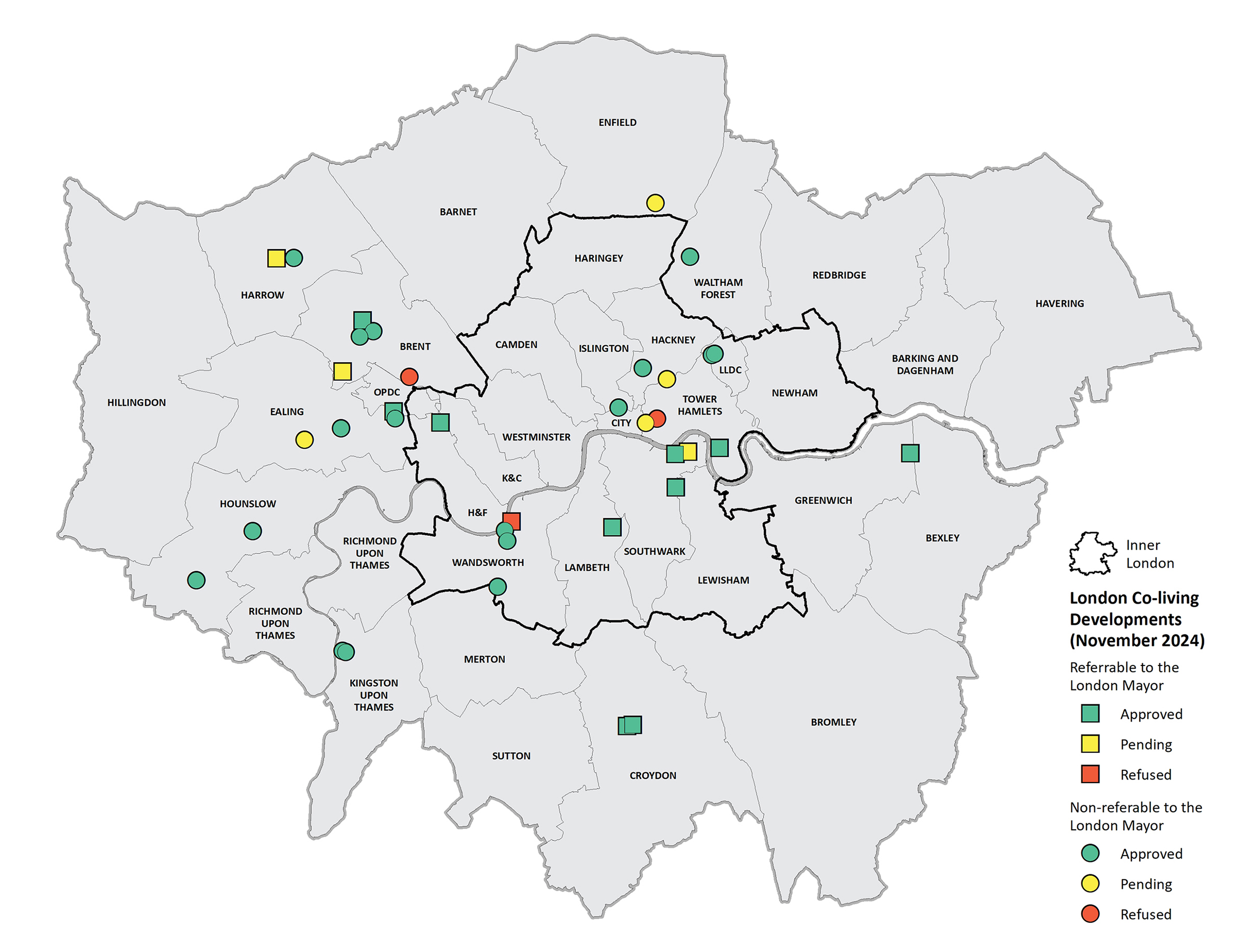

The chart below summarises these recent co-living applications, breaking them down into GLA referable applications (those exceeding floorspace and/or height thresholds for Mayoral referral) and non referable applications, determined locally.

Of the applications which have been refused, the impact on existing housing or the ability to deliver conventional C3 housing on the site was cited as a reason for refusal for two of the applications. This was either because there was an extant permission on the site or the site was in existing residential use.

London authorities adopt different approaches to co-living in planning policy. In Lichfields’ experience, developers and investors focus on those boroughs which have a positive policy position and are politically supportive of co-living.

The map below shows the distribution of the 34 co-living schemes Lichfields’ has reviewed.

Our research has found that there is a broad range of scheme sizes, with the quantum of units ranging from under 50 to over 800 co-living units. The average quantum of these schemes is 295 units.

|

|

No. of schemes

|

Smallest co-living units

|

Largest co-living units

|

Average

|

|

Referable

|

13

|

209

|

817

|

482

|

|

Non-referable

|

21

|

45

|

337

|

197

|

|

Total

|

34

|

|

|

295

|

Scheme Details

We have undertaken a detailed review of the schemes that have been approved and reviewed each development in terms of affordable housing, unit size, communal facilities, car and cycle parking and tenancy agreements. The following section provides a summary of these findings.

Housing Need and Affordable Housing

Our research shows that co-living developments are being brought forward on a range of sites including former office buildings, commercial units, storage and distribution yards, car parks, pubs and vacant sites.

A common requirement for these co-living applications is the need for a housing needs assessment to evidence the local demand for co-living and the role co-living accommodation will play in the local community and an area’s housing stock. Whilst our research identified that many did not provide housing needs assessments, this is partly due to the applications being submitted prior to the adoption of the LPG.

The provision of affordable housing in co-living schemes is varied and dependent on a range of factors including location, authority and scale.

Our research shows that:

- Less than 50% of schemes are supported by a Housing Needs Assessment.

- 54% provided on-site affordable housing provision (discount market rent or conventional affordable housing).

- 75% of referable schemes followed the GLA’s fast track affordable housing route.

- Those schemes which provided on-site affordable housing, typically achieved 35% affordable housing.

Unit Sizes

Within the co-living developments analysed, unit sizes vary from 16 to 24sqm and the average unit size is 20sqm (excluding accessible units).

There is little correlation between the size of the co-living scheme and unit sizes. A scheme’s unit sizes are instead typically determined by the developer, the location and character of the site and the market the units are targeted towards.

Communal Facilities and Amenity Space

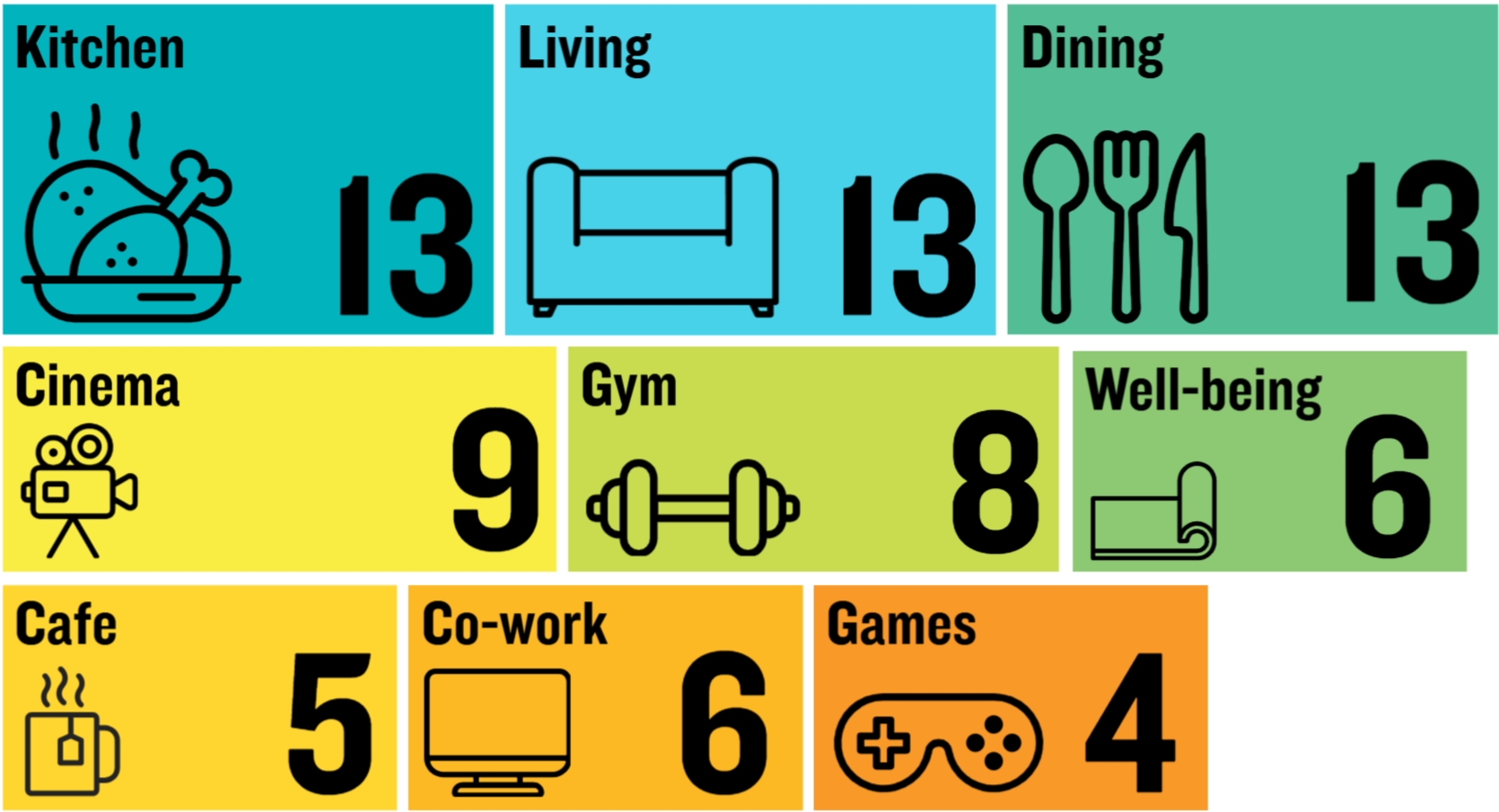

The quantum and type of communal facilities provided within the co-living schemes analysed varied considerably. The most common communal facilities are summarised below. We have looked at the facilities which are provided across the schemes that have been delivered. The graphic below shows the frequency of each type of facility within these developments.

The analysis shows that the average area of a co-living development’s internal communal facilities is 5.5sqm per unit.

There is a broad range in the areas given over to communal facilities in the individual developments analysed; varying between an average of 2.6sqm and 8.1sqm per unit.

Similarly, the average area of communal external amenity space provided is just over 2sqm per unit. The range of amenity space across the developments again varies considerably, with a range between 0.6sqm and 4.2sqm per unit.

Cycle and Car Parking

Cycle parking provision varies considerably across the schemes (0.2 to 1.9 spaces per unit) with an average of 0.9 spaces per unit.

Interestingly, two of the referable schemes in the research provide a cycle hire scheme for residents to use free of charge. In both instances, the developments provided cycle parking levels below London Plan standards, but cycle hire provision was considered by the determining authorities to be a more appropriate offer for future residents.

All of the schemes reviewed were car-free with the exception of accessible car parking spaces.

Tenancy and Management

Our research shows that, in accordance with the London Plan, all of the planning permissions (100%) have a minimum tenancy of three months and two schemes committing to longer minimum tenancies of six months.

All approved schemes were required to provide a management plan as part of the application or post-planning via a condition or S106 obligation.

RETURN TO CONTENTS