The Planning and Infrastructure Act 2025

[1] (the Act) has introduced a proposed system for environmental mitigation, via pooled funds, as an alternative to mitigating via s106 agreements, in England.

Part 3 of the Act ‘Development and Nature Recovery’ provides for Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs), which are a new strategy central to this proposed model.

An EDP will establish a mechanism for addressing specified environmental impacts through coordinated mitigation, which will be orchestrated through a Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) created by a Nature Restoration Levy (NRL).

The primary legislation for EDPs has been introduced by the Government to provide an alternative to site-specific environmental mitigation, usually secured by a s106 agreement. EDPs are intended to create a route to mitigating a defined set of potential area-based environmental impacts. The first set of EDPs are to focus on nutrient pollution, with preparation of a subsequent set of EDPs concerning great crested newts also in progress, as described below. EDPs will be introduced with the intention of improving the efficiency and certainty of making planning contributions towards mitigation of impacts on these matters.

The Act also provides that certain statutorily required project-level assessments or procedures do need to be carried out where impacts fall with the scope of an EDP, as also discussed in this blog. The levy-based approach introduces new considerations in relation to governance, delivery, funding and risk.

We set out below some of the key principles of this new approach to mitigation, including what is set out in the primary legislation and what has been announced in terms of likely detail. After setting out the context we look at:

Context

The Planning and Infrastructure Act 2025 seeks to streamline housing and infrastructure delivery. Part 3 of the Act introduced a new statutory framework for Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs) and the associated Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) and Nature Restoration Levy (NRL) as mechanisms to streamline environmental mitigation within the planning system

[2].

Environmental Delivery Plan (EDPs) are frameworks prepared by Natural England to manage environmental impacts of development on protected habitats or species, having regard to the development plan, the current environmental improvement plan, any Environment Act strategies, and any other strategies or plans consider relevant.

The Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) is a capital fund designed to deliver large-scale projects designed mitigate impacts on environmental features, caused by development.

The Nature Restoration Levy (NRL) allows developers to pay in to the NRF instead of delivering site-specific environmental mitigation. It creates the NRF.

Subject to Regulations, the Act has authorised Natural England to prepare EDPs for defined geographic areas and classes of development, in order to deliver conservation measures aimed at addressing specific environmental pressures and setting a corresponding levy payable by developers to fund those measures.

EDPs will cover specific environmental features and comprise area-based strategies which will be outlined by a map of the development area. Participation and the choice to take forward an EDP lies with the developer, who is able to decide if it is most appropriate for its circumstances. If the developer decides to proceed with the EDP, they will pay the levy in lieu of undertaking project-specific mitigation and cash in lieu payments. The amount paid will be determined with reference, for example to the kind of development and the scale of potential impact of the development.

The EDP will outline the maximum amount of the development the plan accounts for, which may include the area covered by the development, the maximum floorspace, the number of units or buildings, the expected values and for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects, any measurement of scale of the project.

Creating an EDP and how it would apply

In practice, EDPs are intended to reallocate responsibility for environmental mitigation from individual schemes to an area-wide delivery model. Once EDPs are published by Natural England, the required mitigation measures are specified and implemented centrally, and delivery will be funded by the NRF.

Natural England will be able to prepare the EDPs for various environmental issues using best available scientific evidence and informed by a 28-day consultation period with the public and relevant bodies. All EDPs will include

[3]:

-

Definition of the environmental feature

-

Environmental impacts of development

-

The scale and type of development the EDP can support

-

Clear maps to set out the area covered by the EDP

-

Conservation measures to be deployed to address the impact of development

-

A charging schedule that will include costs of the conservation measures, per scheme and mitigation type

The Secretary of State will then consider the EDP and if the conservation measures will correctly mitigate the detrimental effects of development on the conservation status of the environmental feature(s) concerned. Not only must the EDP mitigate the detrimental impacts but the Secretary of State must also be satisfied that the EDP passes the Overall Improvement Test which is designed to secure a net benefit to the environmental feature concerned. The Act stipulates

[4]:

“An EDP passes the overall improvement test if, by the EDP end date, the effect of the conservation measures will materially outweigh the negative effect of the EDP development on the conservation status of each identified environmental feature”.

Following this, the Secretary of State will approve the EDP, and it will then come into effect. Natural England will then continue to report on the EDP until its endpoint.

Local planning authorities and other public authorities have a duty of co-operation with Natural England to give it such reasonable assistance as it requests in connection with the preparation and implementation of an EDP. Such things that a public authority may be required to do include:

-

provision of information to Natural England;

-

the imposition or variation of a condition of development;

-

assistance with the implementation of conservation measures.

In some cases, conservation measure maintenance will need to continue beyond the EDP’s end date, and monitoring may remain in place. Only the Secretary of State can amend the EDP once approved, and a statement would be published in this regard.

EDPs should in turn provide a legally based evidential basis on which to conclude that specific environmental effects will be appropriately addressed, enabling reliance on the plan’s mitigation strategy when determining applications.

Most EDPs are expected to be voluntary and will set out a programme of conservation measures, typically covering up to a maximum of 10 years. They must be based on the best available scientific evidence and can only be used where the measures are capable of meeting the statutory Overall Improvement Test, delivering an overall improvement in the conservation status of the environmental feature concerned.

Where an EDP identifies a protected species, it must set out the terms of the licence that will be treated as having been granted. Under Section 63 the Act, an EDP must specify the terms that are to be treated as included in licences under:

-

regulation 55 of the Habitats Regulations 2017;

-

section 16 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981; and

-

section 10 of the Protection of Badgers Act 1992,

that may be granted to Natural England to facilitate the carrying out of any conservation measures.

As provided by and Schedule 3 of the Act

[5], where a development type falls within the scope of an approved EDP and the developer commits to pay the levy, the effects on the environmental features covered by the plan are to be disregarded and therefore addressed through that framework. In those circumstances, separate project-by-project assessment or individual species licences are not required for impacts fully dealt with by the EDP. Instead, the relevant licensing provisions are treated as having been granted, or are granted to Natural England, in line with the terms set out in the plan.

Essentially, Schedule 3 of the Act expressly disapplies the need for a habitats assessment or species licence in certain circumstances where an EDP is in place.

The Habitats Regulations 2017, the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Protection of Badgers Act 1992 will continue to apply where:

-

no EDP is in place;

-

a developer chooses not to use an EDP;

-

impacts fall outside the scope of an EDP; or

-

the site includes irreplaceable habitats or other features not suitable for the EDP framework.

In those cases, the usual assessment and licensing requirements remain in force.

EDPs will be geographically targeted, aligned with wider strategies such as Local Nature Recovery Strategies, and designed to secure strategic, measurable environmental improvement over time.

Impacts not expressly included within the EDP will remain subject to the assessments/licensing legally required, and LPAs must still be satisfied that the development does not give rise to unmitigated effects outside the EDP’s parameters.

Once implemented, Natural England are required to publish annual reports, and EDP specific reports will be published at the mid-point and end-point of the EDP.

Nutrient neutrality first, newts next

In 'Implementing the Nature Restoration Fund'

[6] the Government says

“the first EDPs will cover developers’ obligations related to nutrient neutrality”. It goes on to explain the catchment areas being prioritised for an EDP where Natural England is

“currently exploring the benefits of developing EDPs” and due to

“significant pressure from development”.

The efficient addressing of potential nutrient neutrality impacts has been an ongoing concern for housebuilders in particular, previously discussed by Lichfields,

here.

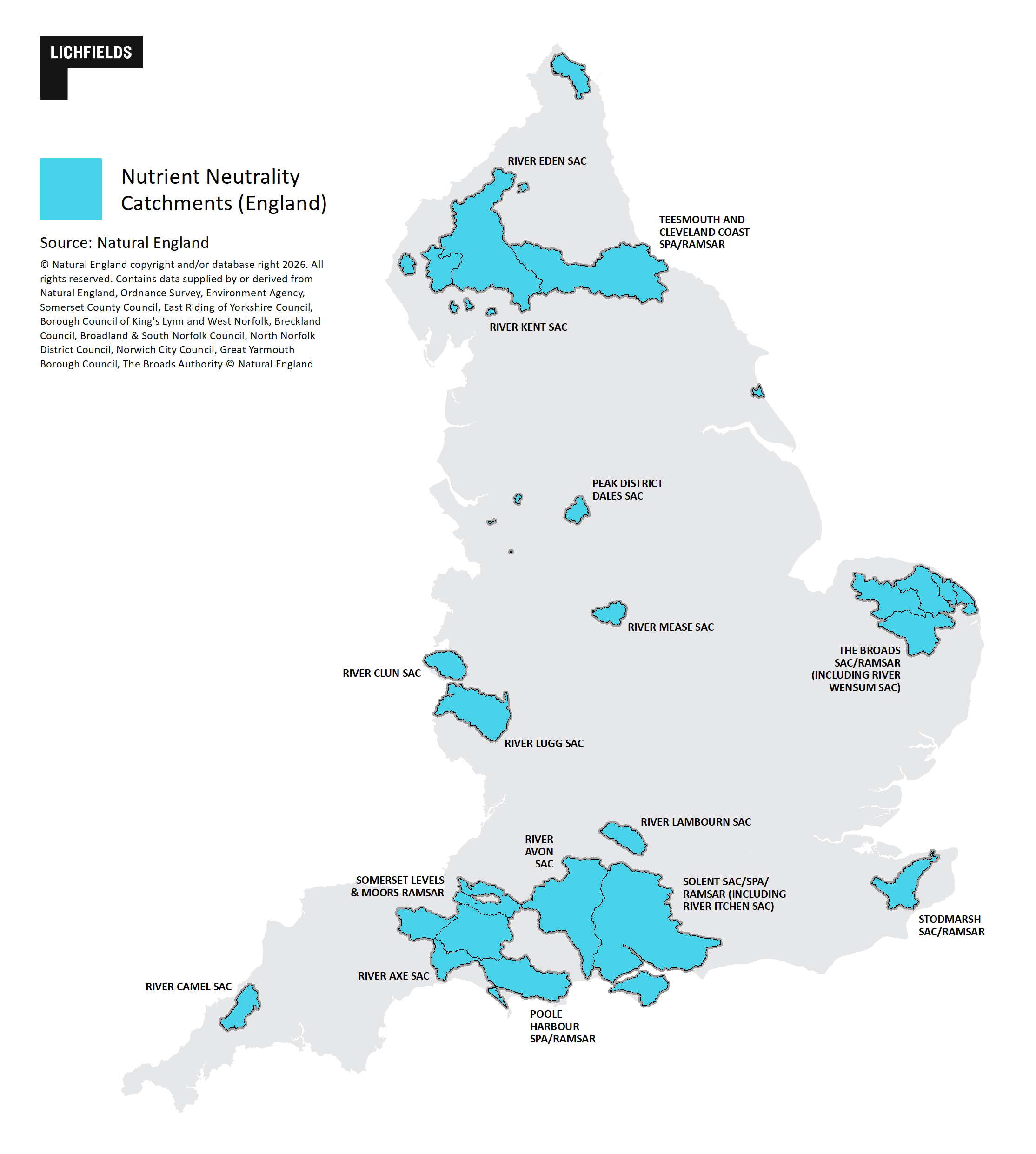

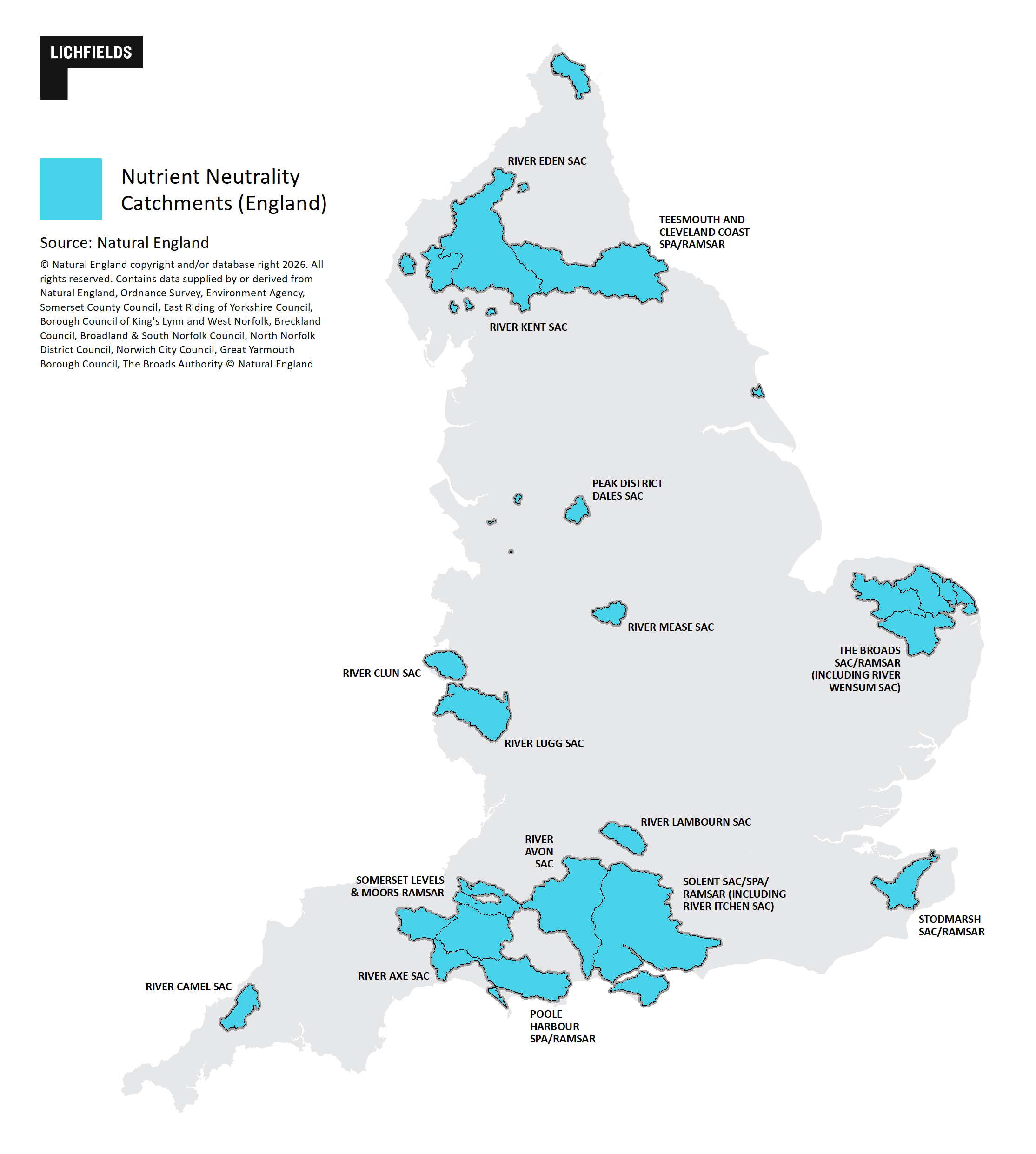

The catchments are shown on the map below and listed

here, with reference to the type of nutrient pollution

EDPs for great crested newts are also being explored

“for development (including infrastructure) in England where GCN are materially present”, according to Natural England. The preparatory work for these EDPs is to utilise District Level Licensing (DLL), with a view to transferring

“the strategic approach taken under DLL” into the NRF. The EDP areas for great crested newts are very broad at present and listed

here.

Natural England is required to notify the Government of its intention to prepare EDPs and has done so for 23 potential EDPs; 16 for nutrient neutrality and 7 for great crested newts

[7], notwithstanding that the secondary legislation required to operate the system has not yet been laid (see below).

In its notification, Natural England said that the first EDPs to be consulted on and submitted as final draft EDPs will relate to nutrient pollution only. While it is preparing

“a number of EDPs in parallel", Natural England confirms that it has noted

“that the Government has committed to not making any EDPs beyond nutrient pollution before making a statement to Parliament setting out the initial learnings from the development and implementation of the first EDPs. This will allow for a test and learn approach to be taken” (see also

this written answer).

S106 agreement or nature restoration levy?

The Government has said that once EDPs are published, developers will be able to use an online platform to obtain an estimate of the levy they will need to pay if they use an EDP for the site. Section 75(1) stipulates that the levy required by developers should not make the site unviable.

For developers, a key consideration is that EDPs are optional alternatives rather than an automatic requirement. Where a proposal falls within the scope of an adopted EDP, the applicant may elect to rely on the EDP for the covered issues, triggering payment of the Nature Restoration Levy at the points set out in the EDP, replacing the need for equivalent S106 obligations (whether financial or physical). The levy can be paid for in instalments if agreed prior to the approval of the EDP. The levy will then deliver mitigation projects at a scale intended to address cumulative impacts more effectively than dispersed, site-level measures. Once the application is approved, developers can rely on the EDP in place of habitats assessment and/or species licence that would otherwise be required for the environmental feature included in the EDP.

The table below compares the EDP and NRF route with negotiating contributions made by s106 agreement, for the same impacts, ahead of Regulations providing further details:

| |

EDP and NRF

|

S106 agreement route

|

|

Procedure

|

Plan-level (Natural England) and consistent on area/issue

|

Site specific planning obligations or conditions dependent on expert advice

|

|

Impacts mitigated

|

Strategic issues defined in EDP only

|

Any site-specific impacts related to the development; bespoke solutions

|

|

Habitats assessment or species licence

|

Requirements met by EDP, in specified circumstances and where the relevant environmental feature is covered by the EDP

|

Continues to be required, where currently applicable

|

|

Engagement by developers

|

At the EDP drafting stage, with regard to plan area, developments that can be mitigated and levy rates. Also need to engage in the local plan, which informs the EDP and may anticipate certain mitigation.

|

In negotiations at the time the s106 agreement is drafted. Engage with the local plan preparation, including regarding policy on developer contributions to address impacts.

|

|

Timing and timescales

|

Negotiation not required at planning permission stage, so could be a faster procedure, albeit not all obligations will be addressed by that EDP in most cases, so s106 agreement still likely to be required, including for environmental mitigation

|

Negotiations of uncertain length. Delivery as specified in the s106 agreement, with reference to stages of the project.

|

|

Funding of mitigation

|

Pooled levy fund managed by Natural England, which must deliver the EDP

|

Developer pays for or delivers mitigation

|

For developers to monitor

Developers should be mindful of whether their site sits within the geographical extent of adopted EDPs as and when they are published, and if the anticipated impacts of their scheme are among the issues expressly covered. Where impacts fall outside the defined scope, the current project-level assessments legally required (e.g. Habitat Regulations Assessment) and the mitigation identified as part of that assessment process, will still be required, potentially alongside EDP participation.

The process for putting an EDP in place, and the process for setting and charging the NRL is similar to the process for putting in place a Community Infrastructure Levy charging schedule. Indeed, in its Memorandum to Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee (on moving to the House of Lords), the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said

[8]:

“The provisions in this section seek to replicate as far as is relevant the powers used in the Planning Act 2008 for the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL). Accordingly, it is the government’s view that there is established precedent for this proposed approach, which is justified in relation to the nature restoration levy as it was in relation to CIL”.

EDPs must be consulted upon, therefore early appraisal of the Nature Restoration Levy is essential. Levy liability should be modelled against the cost, timing and risk profile of delivering mitigation through S106 obligations or conditions, particularly where hybrid approaches may be required. Developers should also anticipate that mitigation projects will be delivered through the Nature Restoration Fund, making transparency around levy calculation, spend assumptions and delivery timescales a key consideration. Developers should be aware that project viability is a consideration in setting levy rates and payment triggers and therefore should discuss options with the LPA early if this is an issue likely to arise in the development process.

EDPS may be amended on request of Natural England or by the Secretary of State, however the EDP cannot be amended so that it no longer applies to a development in which the developer has agreed to pay the NRL. If an EDP is amended, it will go through the consultation process again.

EDPs may not capture all relevant environmental receptors or pathways. Developers should expect planning permissions to retain fallback conditions or S106 clauses where impacts sit partially or wholly outside the EDP’s scope.

Clarity around monitoring, reporting and adaptive management arrangements is essential, particularly where environmental outcomes are dependent on longer-term delivery of strategic mitigation projects.

Implementation timescales

Part 3 of the Act is in force, with the exception of one section (s91, which requires annual reporting by Natural England on all EDPs in force). This means that the Government is able to draft the necessary Regulations and it has indicated that it is doing so:

“This includes:

levy regulations – these will set out how the levy (a charge paid by developers) will operate and how charging schedules will work for each EDP.

prioritisation regulations – these will set out the appropriate prioritisation of the different ways of addressing a negative effect of development on a protected species, or on a protected feature of a protected site”.

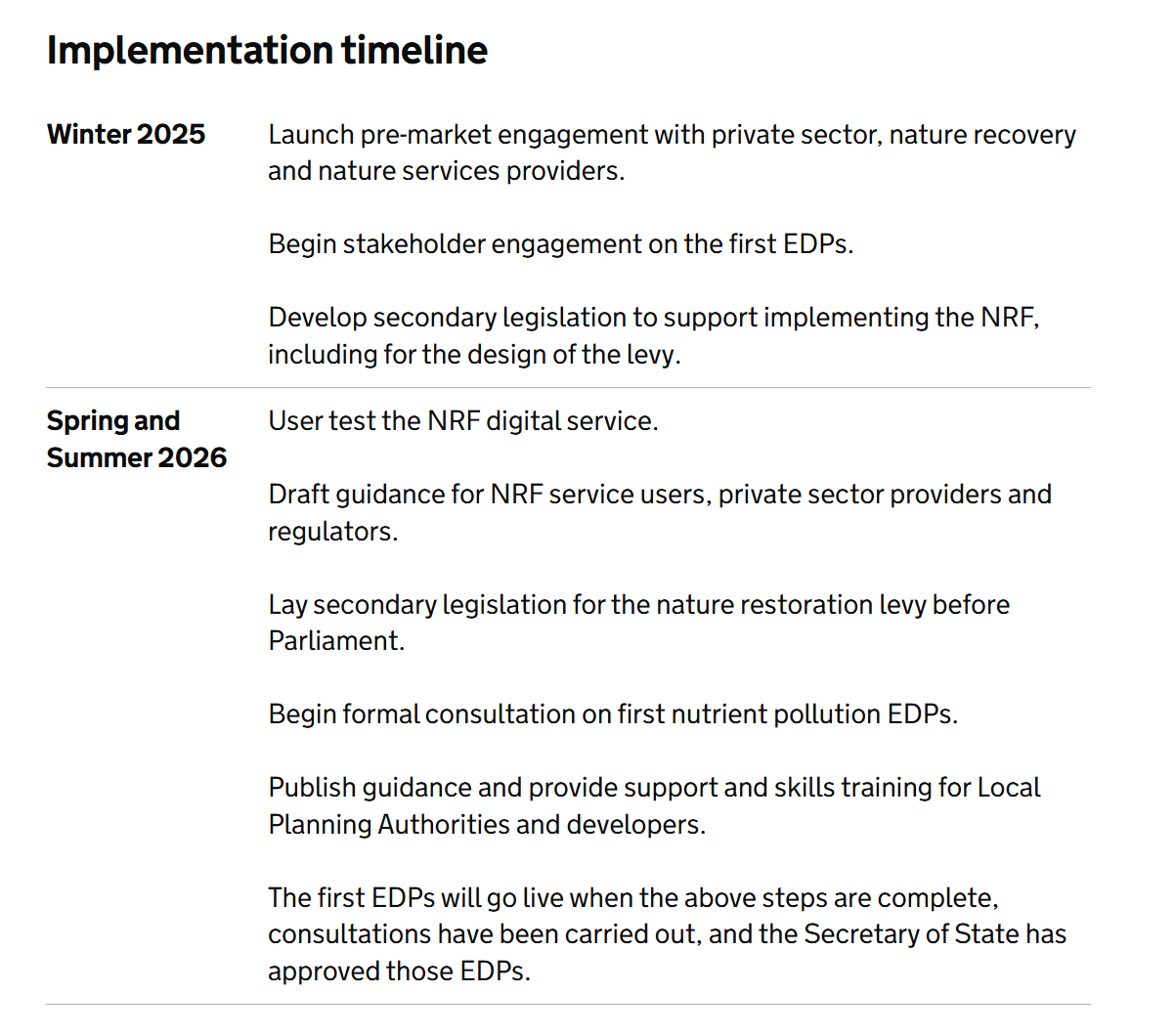

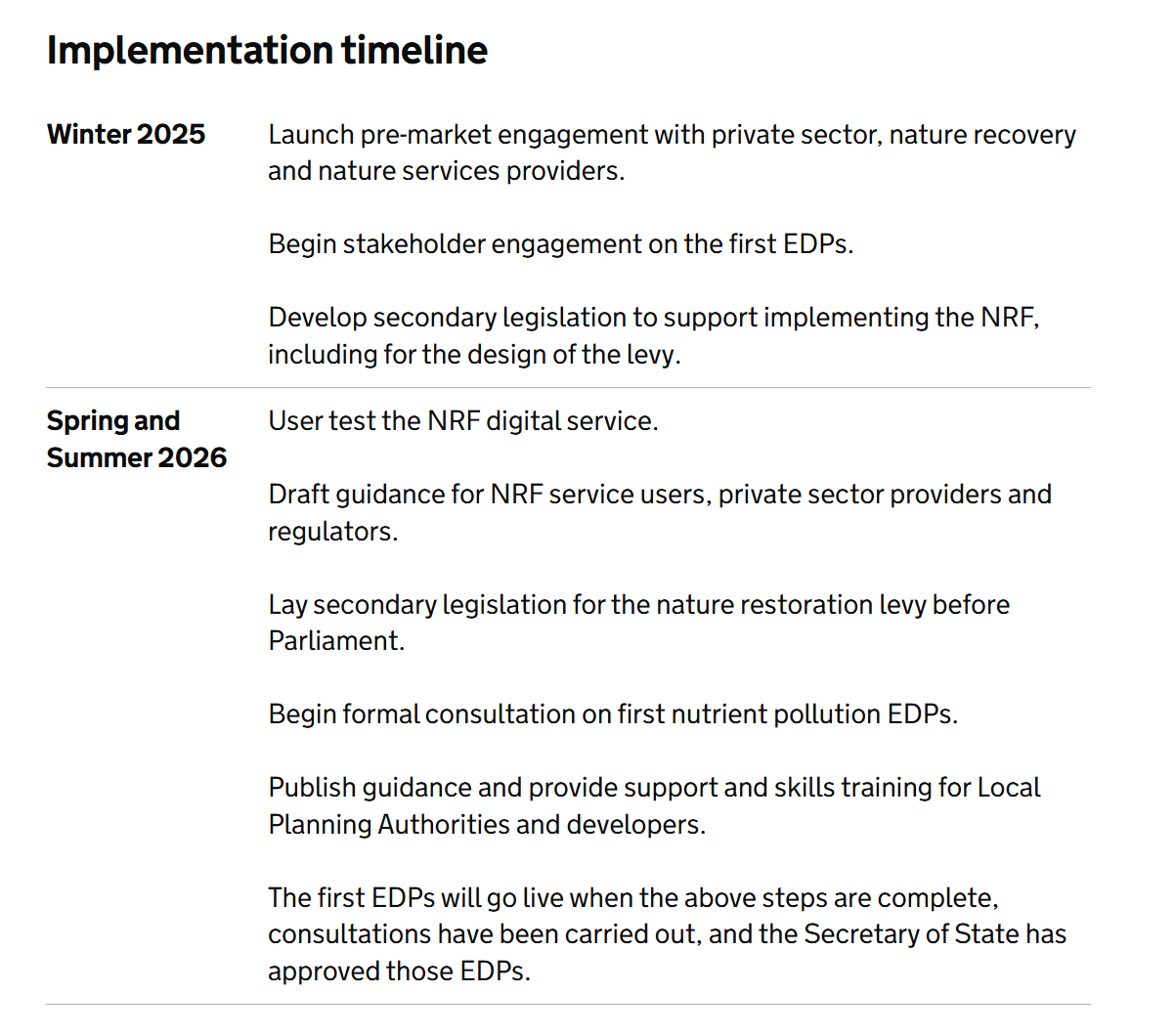

'Implementing the Nature Restoration Fund' sets out the Government and Natural England’s intended implementation timescales, including for secondary legislation:

Conclusion and comment

Environmental Delivery Plans and the Nature Restoration Fund represent a significant shift in how environmental mitigation is integrated into the planning process, offering developers a more strategic and potentially faster route to compliance for defined impacts. However, the model does not eliminate site-level responsibility, and its success in practice will depend on careful scoping, transparent levy setting and credible delivery mechanisms.

Furthermore, this Part of the Act came under heavy scrutiny as it made its way through Parliament (see, for example, planning lawyer Simon Ricketts’ discussion of concerns raised, written in August 2025). The Regulations will need to capture many eventualities, to avoid a repeat of the many versions of the CIL Regulations that they are to be based on. Each individual EDP being drafted is also likely to be heavily scrutinised. The target is for some EDPs to be in place by the summer. Where this is achieved, the consultation processes will be swift. Therefore, those developers wishing to partake in the process should be alive to the timescales and actively engage in order that EDPs provide them with a viable alternative to securing mitigation via s106 agreements.