The lost and the delayed

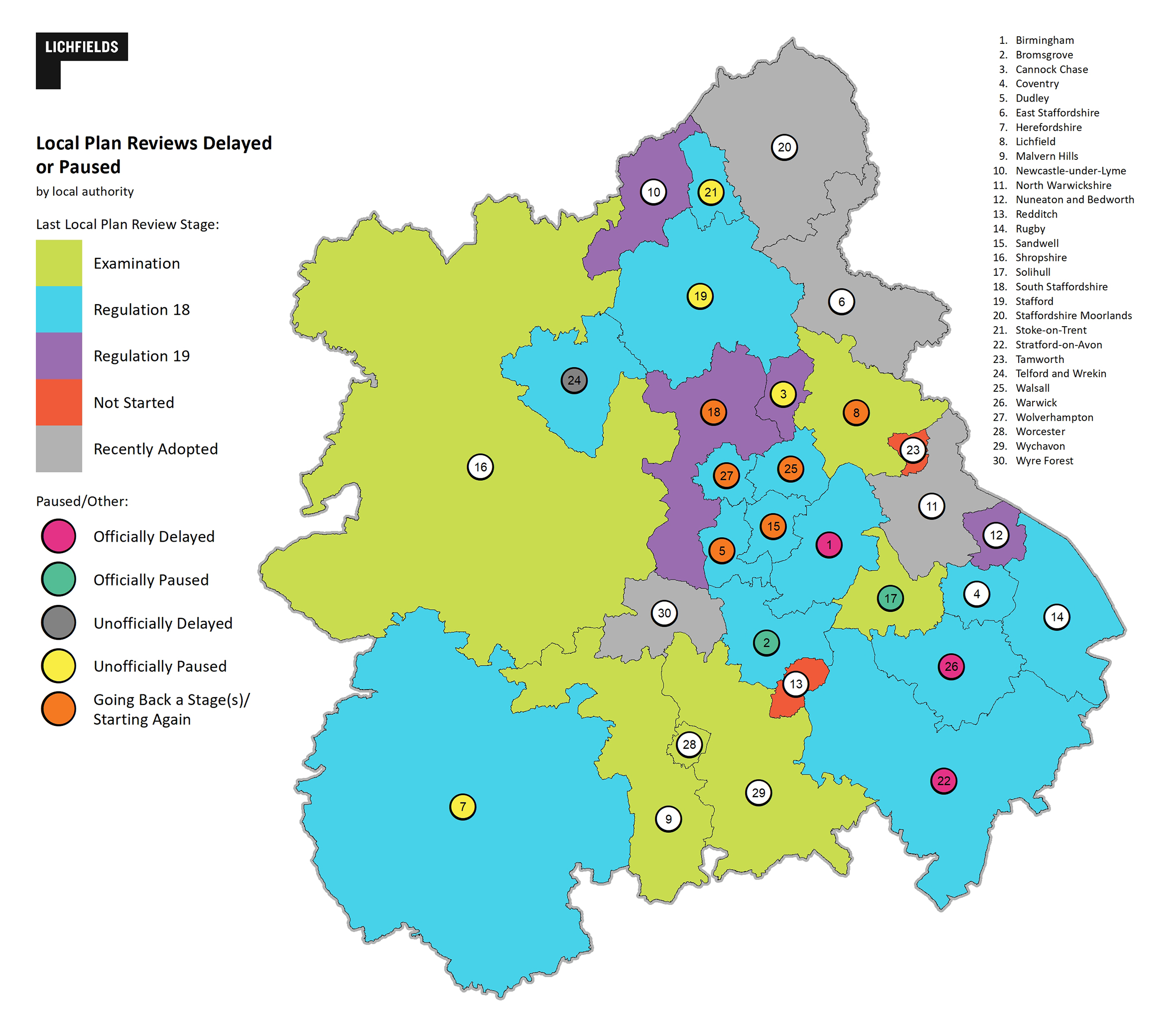

Based on the analysis previously set out, 18 LPAs within the region are, or at least should be, preparing plans. So what are the implications of this perfect storm on plan-making and delivery?

Delayed housing and employment allocations

Of the 18 authorities that have delayed the preparation of their Local Plans or should be reviewing their plans, only six draft plans were sufficiently far advanced to contain draft housing and employment land allocations – when accounting for the former joint BCA Review counting as one singular plan for four LPAs.

Obviously, given the intended rolling nature of plan preparation, to meet their identified needs, many of these plans housing land supplies factored in extant permissions and saved allocations from previous plans. This ensures that there is generally a pipeline of supply for some time, allowing new allocations to feed the supply – naturally – later on; whether the existing supply fully addresses housing and employment needs in that interim period is arguably another question.

Nevertheless, whilst some of these draft allocations will come forward in the future (although not in all cases – for example, where draft allocations comprise of land that is currently within the Green Belt and which might therefore not come forward), their formal allocation and delivery will be delayed. That means that they will take longer to build out, thereby reducing the need for additional allocations in future plan reviews – all in all reducing the overall long-term delivery of housing.

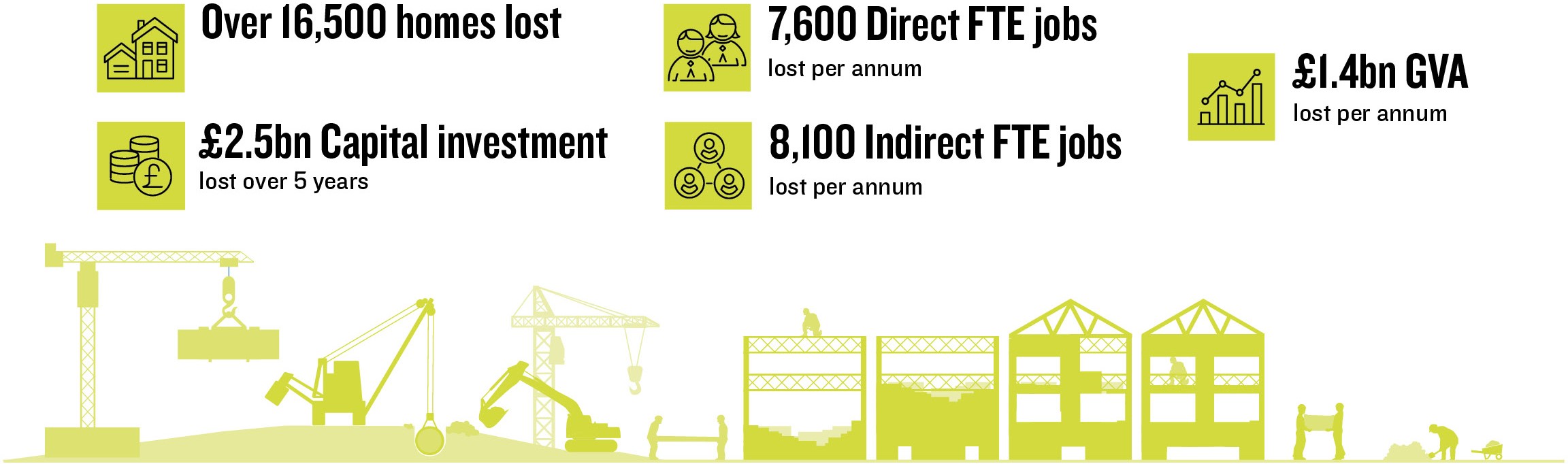

So, within the six delayed draft plans, when accounting for extant supply, some c.55,000 houses on draft-allocated housing land, and 730 ha of draft-allocated employment land, is being held up from delivery across the region. It is important to note that this housing and employment growth is not ‘lost’, but rather delayed. Whilst some of these allocations may be de-allocated as a part of some of these plans revisiting housing needs and spatial strategies due to going back a stage or indeed starting again, it is fair to assume that most of these allocations will come forward at some point in the next few years. However, the implications of these delays are quite striking.

Indeed, at an average of 2.4 people per household in the West Midlands according to the 2021 Census, this equates to enough new homes for over 130,000 people, and represents delayed capital investment of over £8 billion based on average build costs

[13]. Similarly, applying a standard 40% plot ratio as used in employment land evidence, 729 ha becomes over 9 million sqm of employment floorspace which has got stuck in the system, enough for tens of thousands of new jobs. In fact, if we apply the existing split of office/B2/B8 floorspace across the West Midlands, which is roughly 15%/70%/15%

[14], and use standard employment densities, the potential employment which could be supported by these delayed allocations could be as high as 85,000 jobs.

RETURN TO CONTENTS