This blog forms the first in a series on the implications of the Cardiff Capital Region City Deal on planning for housing in South East Wales.

With the Cardiff Capital Region (CCR) City Deal programme now underway, there are compelling reasons to believe that South East Wales is an area on the up.

The City Deal, worth £1.2 billion, aims to provide a 5% uplift in GVA and create up to 25,000 new jobs by 2036, representing a 40% increase above forecasted levels of growth. However, by taking a step back and viewing the CCR in its wider UK context, we see a less confident picture – one of a region with a smaller, more fragile economy that has the potential to fall behind in relation to the rest of the country if care is not taken to support its future growth. As we explore in this series of blogs and in

our latest Insight Focus, a vital part of this support is the provision of a sufficient number and appropriate mix of new homes in the right locations.

Cardiff is part of the Core Cities Group, which represents the ten largest and most economically important cities outside London. Each of the Core Cities is, in fact, a city region, which includes a number of local authority areas (see figure 1). These city regions have been identified as comparators by the Growth and Competitiveness Commission (established as part of the CCR City Deal). In this blog, I compare the economic performance of the CCR against these other areas and identify the initial implications for housing policy.

Figure 1 Core City regions

Source: The Core Cities Group

Economic status

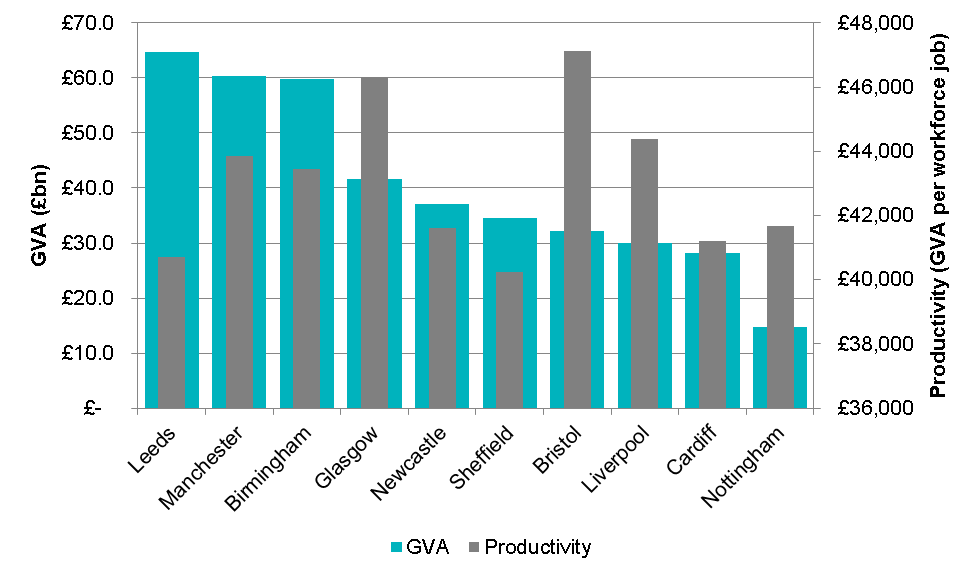

With an annual GVA of £28.3 billion in 2017, the CCR has the second smallest economy of the 10 UK Core City regions. Taking into account its size, the CCR currently has the third lowest level of productivity, at £41,192 GVA created per workforce job, whilst Bristol has the highest at £47,129 per job (see figure 2). Interestingly, despite having the largest economy at £64.7bn, Leeds has the second lowest level of productivity at £40,718 per job. This highlights the importance of considering both indicators in assessing the economic well-being of an area. The fact that the CCR performs poorly in relation to each is troubling.

Figure 2 Total GVA / productivity by Core City region (2017)

Source: Lichfields analysis of Experian data (March 2017 release)

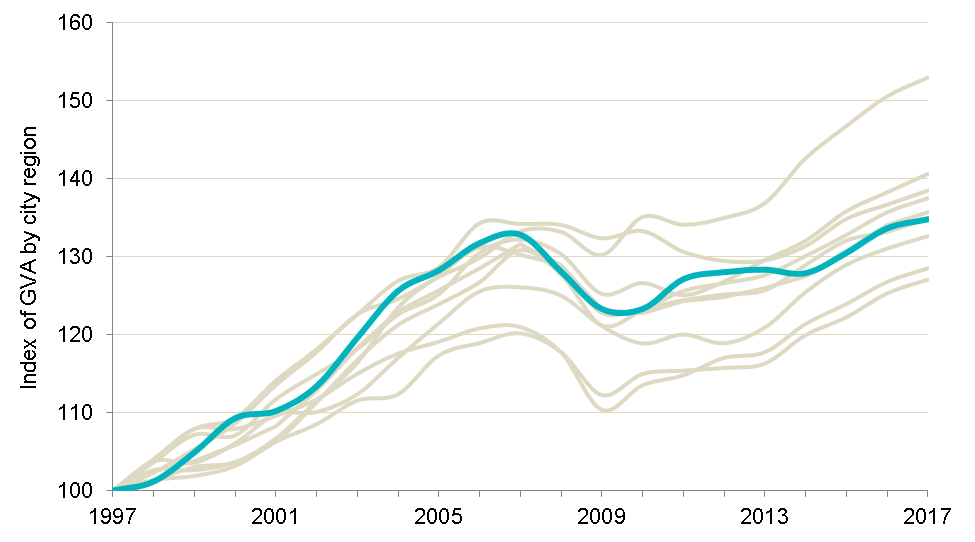

The CCR achieved the second highest level of GVA growth among the Core Cities between 1997 and 2006. However, by 2014 its GVA growth had fallen to the lower half of the Core Cities group and it took nine years for its economy to recover to pre-recession levels following the financial crisis in 2007, such that by 2017 it was only middle-ranking in terms of GVA growth (see figure 3).

Figure 3 GVA all sectors: indexed to 1997 levels

Source: Lichfields analysis of Experian data (March 2017 release)

Similarly, the CCR experienced the highest level of workforce job growth of all of the Core Cities between 1997 and 2006 but had been overtaken by half of the other Core Cities by 2017.

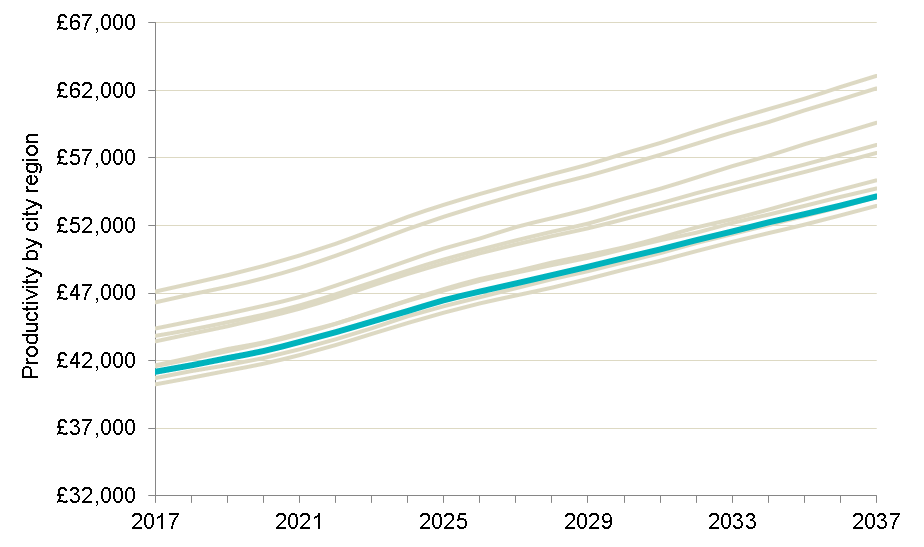

If current trends continue, the CCR’s economy is expected to remain in the middle of the group of Core Cities in terms of GVA, workforce jobs and full-time equivalent (FTE) job growth in the period from 2017 to 2037 (see figure 4). However, its productivity is anticipated to remain at the lower end of the Core Cities group, with the smallest increase (31.5%) of all of the city regions, compared to an average increase of 32.9%.

Figure 4 Forecast productivity

Source: Lichfields analysis of Experian data (March 2017 release)

High tech sectors

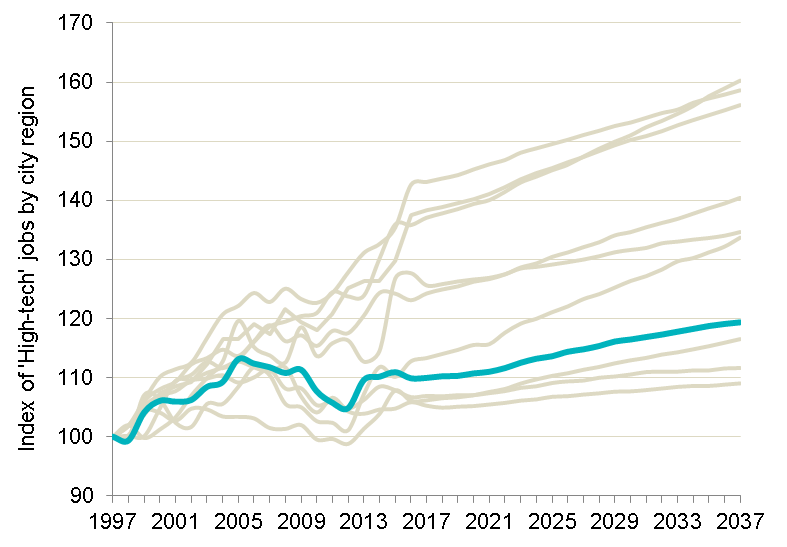

As key drivers of productivity and sources of well-paid jobs, the high tech sectors are an important indicator of economic health. Between 1997 and 2017, there was a 10% increase in high tech jobs in the CCR (the third lowest across the Core Cities), compared to the highest increase of 43.1% in Sheffield. From 2017 to 2037, the CCR’s high tech sectors are expected to grow by only 8.6%. This indicates that a continuation of current conditions will not be sufficient to deliver the desired boost in highly skilled jobs.

Figure 5 Index of high tech jobs by city region

Source: Lichfields analysis of Experian data (March 2017 release)

Part of this issue relates to the difficulty faced by the CCR in losing graduates, particularly in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects, to other areas – despite benefiting from internationally competitive higher education and further education institutions.

| |

|

|

| |

Economic headlines

Current economic status:

- 2nd smallest economy of the ten UK Core City regions, with an annual GVA of £28.3 billion in 2017 (see figure 2).

- 3rd lowest level of productivity (GVA per workforce job), with £41,192 GVA created per workforce job, whilst neighbouring Bristol has the highest productivity at £47,129 per job (see figure 2).

- Nine years for its economy to recover to pre-recession levels following the financial crisis in 2007.

- Experienced the third lowest increase (10.0%) in high technology jobs across the Core City regions between 1997 and 2017.

If current conditions continue:

- Expected to remain at the middle of the group of Core City regions in terms of GVA, workforce jobs and FTE job growth in the period from 2017 to 2037.

- Anticipated to continue at the lower end of the Core Cities group in terms of productivity, with the smallest increase (31.5%) of all of the regions between 2017 and 2037.

- Only 8.6% growth expected in high tech sector jobs between 2017 and 2037.

|

|

| |

|

|

The need for the CCR City Deal is clear. Without appropriate support and investment, the future success of the CCR economy is uncertain. It is also worth bearing in mind that a number of the other Core Cities have their own City Deals, and all will be seeking to improve their future economic performance.

Even with the City Deal in place, meeting its goals will be challenging, particularly given the modest projected growth in high tech sectors in the CCR. In order to increase high tech growth, it will be important to address the issue of retention of graduates, particularly in STEM subjects.

Making the link between the economy and housing: we need workers

The vibrant economy of the CCR City Deal needs a vibrant and growing population, including young people and highly skilled workers. The CCR can only hope to attract and retain workers with these characteristics if it can offer a sufficient number of homes of the right type and quality in suitable, accessible and desirable locations. There is also the moral duty to accommodate the area’s ageing population and those who are unable to afford market housing, many of whom (in both categories) will still be active contributors to the local economy.

The City Deal programme is taking place amid a complex policy landscape of adopted and emerging Local Development Plans and Plan Reviews, the proposed Strategic Development Plan at the regional level and the National Development Framework for Wales. There are a number of key questions which will need to be debated over the coming months, including how to coordinate the next set of development plans and their policies, how to boost housing delivery, and what constitutes an appropriate distribution of new homes across the region.

We will explore these issues and what they mean for housing policy in South East Wales in our forthcoming blogs in this series.

© Lyndon Griffith / Alamy Stock Photo