The next step towards the Government’s stated ambition for strategic planning - universal coverage of spatial development strategies (SDS) across the country - was

announced for consultation on 12th February 2026. If the system works as intended (and given both past history and current political vicissitudes, it is inescapably an ‘if’), then SDSs could eventually become the key development plans for longer term strategic decision-making across much of the country.

In this initial analysis we consider the make-up of the new geographies, and explore some metrics related to two of their key priorities: meeting housing needs, and growing the economy, all set out within our interactive SDS Data Dashboard, to which we will be adding metrics over time.

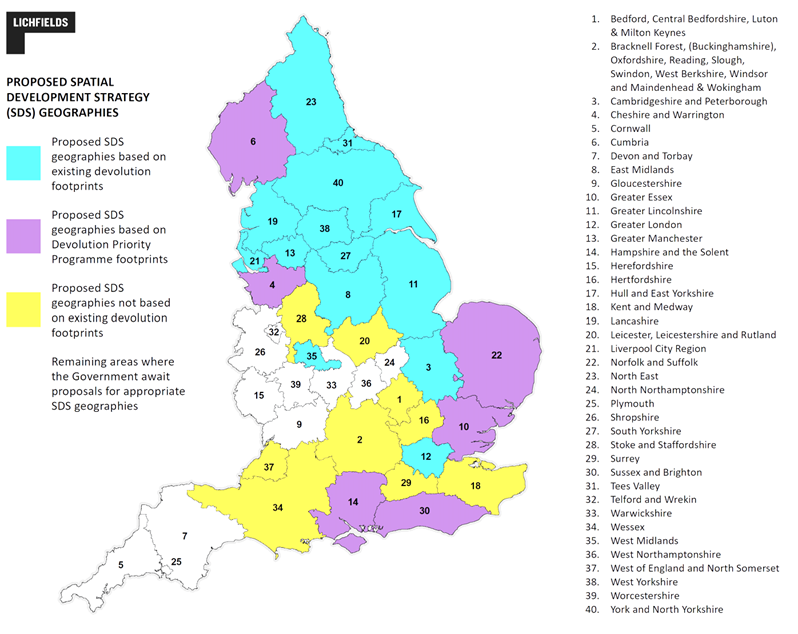

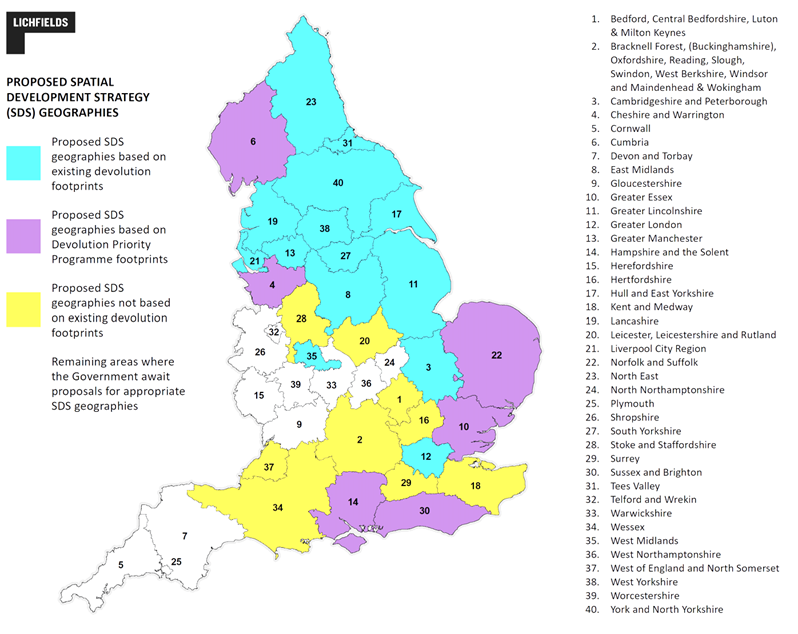

The announcement provided (for consultation) the Government’s preferred geographies for SDSs. For some time, more than half of England’s population has lived in areas led by Mayors; these settled geographies are – mostly

– continuing in the same form, and across at least seven of the major cities, the preparation of SDSs is already underway (as we

observed in December).

For much of the rest of the country, those in purple and yellow in Figure 1, last week’s formal announcement begins to shed light on these areas. However, with significant proportions ‘yet to be confirmed’ (shown in white) there is still a way to go.

Figure 1: Proposed Spatial Development Strategy Geographies

Our SDS Data Dashboard

For each of the proposed SDS geographies we have assembled a small number of the key indicators to explore each area, initially focused on the twin challenges of housing and economic growth. We provide commentary below alongside a mapping of each indicator.

Table 1: SDS Key Indicators

Meeting housing needs

SDSs are intended to ensure that sub-regional areas can effectively plan to meet their housing needs over twenty years.

Figure 2 shows how this maps out using the current standard method for housing need. To meet these needs across the SDS area, Strategic planning boards will therefore need to: “

re-distribute housing need and other development needs between local planning authorities and may include specific policies for development or to be taken into account by local planning authorities when preparing or updating their local plans".

In total, over 20 years, the SDS system will need to make provision for some

7.4m homes, of which 5.7m are outside London.

SDSs in areas with existing devolution deals such as Manchester, the West Midlands and the East Midlands will need to apportion 17,000, 12,400 and 11,000 homes each year, respectively. New SDS geographies such as ‘Thames Valley’

Kent and Medway and Wessex will need to apportion 17,000 and 14,000 per annum respectively under their emerging geographies. For context, all of these are larger than the equivalent for West Midlands or West Yorkshire.

Figure 2 – 20 Year Housing Need based on Standard Method

Analysis of recent housing delivery rates shows that for many SDS areas, housing delivery over the last three years is less than 60% of the local housing need (Figure 3) indicating that new strategies will need to demonstrate a real step change in provision, most likely pursuing spatial approaches to land release that the local plans of the last 15 years did not consider.

Across the South East those preparing SDSs will face some of the greatest challenges in meeting housing need. London, Hertfordshire, and Surrey will require building at between 120-150% of the current rates (over the last three years). A similarly big task faces much of the South West of England including Cornwall and Plymouth, Devon and Torbay, where the Government says it awaits to “hear proposals for appropriate SDS geographies”.

Meanwhile, a small number of SDS areas – those shown in blue on Figure 3 – have been successfully delivering homes at a level consistent with what their new SDS will need to secure for the next 20 years.

Figure 3 – Recent housing delivery against Standard Method

In increasing housing delivery (and indeed, providing for other land-hungry uses), it will be necessary to consider the presence of relevant environmental and other designations that restrict development (See Figure 4), and how that relates to functional economic and market geographies that might extend beyond SDS areas. This is in the context that the consultation draft NPPF proposes (Policy PM14) that the SDS test of soundness should be based, inter alia, on the plan being ‘positive’, with a “strategy that seeks to meet objectively assessed needs, and is based on effective joint working on cross-boundary strategic matters. A strategy which does not provide for objectively assessed needs should be considered an exception, and only where it is evidenced that stringent efforts have been taken to meet those needs through cooperation with other strategic planning authorities.”

A particular challenge will arise in the more tightly defined SDS areas such as the West Midlands Combined Authority where the SDS has an acute challenge (one with which the wider West Midlands RSS tried and failed to grapple)

accommodating its own development needs within its current administrative boundary. Across the WMCA SDS area, recent delivery is around 65% of the aggregate housing need, but three quarters of the land area is either already built-up or subject to national planning restrictions or the green belt.

In this, and many other SDS areas, reviewing green belts will be critical to achieve sustainable patterns of development. But the big questions remain as to how effective will be the SDS process in engaging with overlapping housing market or functional economic areas without falling into (a larger-scale version of) the local duty to cooperate trap.

Figure 4 – Constrained land (green belt and national planning constraints) as a share of total land

Supporting economic growth

Each SDS will be expected to plan for economic growth at the strategic level within its area (see draft NPPF Policy PM1). There is no employment land equivalent to the standard method for housing need, but projecting workforce growth, using Experian forecasts over the next twenty years, shows varied challenge for SDS (See Figure 5)

,. Employment growth is projected for around

4.9m jobs by 2045, an increase of 15.4% in compound growth over the period to be addressed.

The geography of workforce growth shows a continued ‘North-South divide’ with hotspots including Central Bedfordshire

. Within this overall scale of employment, there will also be structural economic changes that all SDS will need to address and ensure the right land and infrastructure is provided to attract the indigenous and exogenous investment necessary for improved productivity and global competitiveness.

Figure 5 - Workforce Growth Projections 2025-45 (%)

Without a prescriptive direction on how to measure ‘need’ (as reflected in the draft NPPF PM1 2 (c)) each SDS will be looking at building on the existing strengths of their economies and supporting growth in key industries identified nationally.

While SDSs will need to plan strategically for growth across the whole economy, the eight sectors identified in the industrial strategy are clearly earmarked for consideration, namely: Advanced Manufacturing, Clean Energy Industries, Creative Industries, Defence, Digital and Technologies, Financial Services, Life Sciences. There are clear geographical strengths and, in some locations, clusters of growth that will need to be supported in emerging development plans (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Industrial Strategy Priority Sectors Location Quotient

NB: Location Quotients are a measure of each industry’s concentration in an area (in this case SDS) compared to a larger area (in this case England). 1+ indicates a strength, to a maximum of 2.

Some ongoing challenges

With the task ahead – planning for 7.4m homes, unlocking investment for a changing economy and 4.9m extra jobs, infrastructure provision and nature recovery – so significant, the return to strategic planning has been largely welcomed across the sector. And why not? Who doesn’t want nice big plans that provide answers to the big questions? But of course the process to get there comes with challenges that extend well beyond the logical (and largely straight forward) nuts and bolts of what is to be laid down in regulations, policy and guidance. Many of these are familiar to observers and participants in previous iterations of strategic planning: a lack of political consensus; strategies that duck the big issues; bold ambitions that are eviscerated or revoked; delays and misalignment of timescales across tiers of plans and between areas.

The extent to which these risks manifest themselves will determine whether ‘strategic planning’ becomes more than an industry in itself (and a conversation piece for planners) and provides what it could and should – a mechanism for genuinely addressing strategic cross-boundary requirements and ensuring the national growth, infrastructure and nature recovery imperatives are met.

The Government is aiming for full SDS coverage by the end of the parliament. This appears ambitious, but the consultation on geographies, progress of the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill, the direction of travel in the draft NPPF and the Planning and Infrastructure Act 2025 shows the Government’s intent.

However, there remain tensions inherent in the structure. Unlike in the Capital where the London Plan is subject to scrutiny by an elected Assembly, elsewhere, the equivalent is provided by a cabinet of council leaders, who - with a simple majority - can veto submission. In many of the strategic planning authorities there are four or five councils alongside a mayor, so the potential for local elections (themselves in flux)

to tip the balance against an emerging SDS which might have previously enjoyed support is a live prospect even for those existing Combined Authority areas with momentum. The prospect of change – with local government reorganisation, devolution processes – including Mayoral elections delayed to 2028

– adds to the uncertainty.

The Government’s consultation recognises the potential for SDS to falter with a change in leadership:

“A strategic planning authority can change and re-consult on an SDS up to the point of submission for Examination. After that point, the SDS can only be withdrawn if it fails at Examination, if the Secretary of State directs that it should be withdrawn, or if the strategic planning authority votes against adopting it.”

It is early days and a mixed picture. The strategic planning landscape in some areas continues to look auspicious, notably the Combined Authorities with mayors who are keen to win the race to be first to adopt an SDS.

But one cannot help but think that the system created by the Government was best suited to an administration with an almost inevitable prospect of at least two full terms of parliamentary majority and the strength of writ to impose its national planning will (over local planning 'won't') throughout most of that period. But with its electoral prospects now much less clear, and the political map of England likely to evolve in the May of each of the next three years, the spectre of a modern-day version of the notorious “

Caroline Spelman letter” looms large.

Footnotes

The West of England Mayoral Combined Authority (WEMCA) will now work in partnership with North Somerset to establish a Strategic Planning Board (SPB) for the area’s SDS, this will extend beyond the WEMCA.

See Policy PM1 in the Consultation Draft NPPF

MHCLG 2026, Areas for producing spatial development strategies

The official name is catchily: Bracknell Forest, (Buckinghamshire), Oxfordshire, Reading, Slough, Swindon, West Berkshire, Windsor and Maidenhead and Wokingham

As relayed in this Planning news item from 2009 reporting on the work carried out by Lichfields (then Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners) for the Government Office for the West Midlands, due to concerns that the regional planning body was not planning for sufficient housing growth and had a strategy that was overly dependent on unrealistic urban housing targets (£). The NLP report is here

The 1985 White Paper Lifting the Burden (Cmnd 9571) criticised Structure Plans for being “replete with generalities…and vague aims” and slow to prepare and update: “plans become out of date and tend to lag behind need and conditions. The twin priorities of generating jobs and providing sufficient land for housing have not been reflected fully or quickly enough.”

Through the wide ranging intervention powers available to it through the Planning and Infrastructure Act.