Late last year a

Written Ministerial Statement (WMS) was released that – among other things – signalled four key changes to the ‘Five Year Housing Land Supply’ (5YHLS) policy test. My December 2022 blog (see

here) concluded that the changes proposed would water down the 5YHLS test, making it less effective, would result in fewer homes being built, but might lead to more plans being adopted (as part of a wider package of changes). However, that blog was written in a vacuum without the benefit of the proposed policy wording.

Now we have a consultation on on ‘

Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill: reforms to national planning policy’. This seeks views on an updated NPPF with revised text (see

here) alongside wider proposed changes to the planning system and questions (see

here). My colleague Jennie Baker has already written a blog looking at the broad changes proposed (see

here) with a further analysis by Ed Clarke on the changes proposed to the Housing Delivery Test (see

here). There will be more blogs coming, so subscribe at the bottom of this page for alerts.

Back to 5YHLS. How have the changes proposed back in December been translated in to draft amends to the NPPF that are planned to become policy in ‘Spring 2023’?

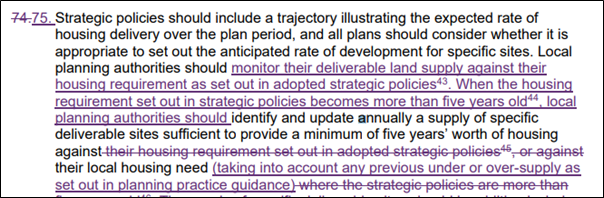

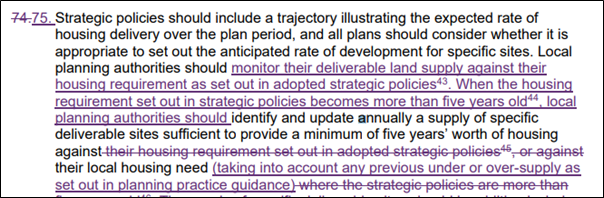

1) The obligation to demonstrate a 5YHLS would end for some

The Government proposes through the revised NPPF that any LPA with an up-to-date requirement – i.e. a requirement contained in a plan adopted in the past five-years or a plan which has been reviewed and found not to need updating – will not need to demonstrate a 5YHLS. This is intended to protect LPAs who have up to date local plans from the ‘threat’ of speculative housing applications in situations where they cannot demonstrate a five-year supply of deliverable sites.

This raises at least two questions:

1. When a plan is first adopted, in order to be found sound it will have been required by the NPPF (para 68 as is, para 69 as proposed) to provide for ‘specific deliverable sites’ for years 1-5 of the plan period, and then only ‘

developable’[1] sites for years 6-10 and, if possible, years 11-15. The Government’s proposed changes mean an LPA won’t have to demonstrate a 5YHLS again until it tips into year six of the plan. But of course as early as year two, its trajectory will begin relying on housing sites in ‘year six’ of the trajectory that were – at the time of plan preparation – only considered ‘developable’ and may not have become deliverable in the meantime for whatever reason. By the time of year four or five, the ability of a plan to meet its housing requirement figure will be largely dependent on sites (in years 6-10) where the confidence over availability and achievability was by no means assured when the plan was prepared. Moreover, there will be no check and balance mechanism for remedying any gaps in the trajectory that may opened up in the meantime.

2. The initial five-year protection from an up-to-date plan is proposed to be rolled forward by means of the LPA reviewing its plan and concluding it does not need to be updated.

Famously[2], a LPA can review its own plan as judge in its own cause without formal planning scrutiny (marking its own homework) and if it concludes its plan does not need updating, the protection is signed off for another five years; by this stage, the plan trajectory (extending for years 10-15) would likely be relying on a Plan where its NPPF (para 68 as is, para 69 as proposed) requirement is only to identify “developable sites or broad locations for growth, … where possible”. In essence, an LPA could conceivably have ten or even more years of protection from five-year land supply scrutiny even if it was relying on a trajectory, last scrutinised five years previously and based on developable sites that may not have been converted into deliverable supply.

To add context to the above, we have already shown how the accuracy of trajectories for ‘deliverable’ sites – i.e. sites we have more confidence in than ‘developable’ ones – quickly deteriorates past ‘year 1’ with clear optimism bias the further you look out in the context of 5YHLS positions

(in the London context at least)[3]. It is therefore likely safe to assume the delivery trajectories for ‘developable’ sites are less accurate. In reality, the trajectories for such sites are based on some reasoned crystal ball gazing at local plan examinations.

Given the inherent uncertainties involved in predicting delivery of sites at the outset of the plan period, it is difficult to draw any other conclusion than that the lack of requirement to demonstrate a rolling supply of deliverable sites (and the consequential absence of access to the ‘tilted balance’ where this is not achieved) will mean fewer homes being planned for, with problems getting progressively worse.

One question the proposed amends do answer though is that regardless of whether a 5YHLS needs to be demonstrated, all LPAs must monitor their deliverable supply. This is on one hand positive because it is simply good planning to know what supply is on the books compared to a given requirement. On the other hand, for reasons explained above, there is no recourse for being unable to demonstrate a 5YHLS and therefore less scope (or incentive) to question whether a Council’s stated supply is robust. We can therefore speculate that such monitoring reports may, in many cases, be unrealistic: why would an LPA put lots of effort in to monitoring supply and gathering deliverability evidence to create a robust position when it has so many other pressures and it does not – in policy or practical terms – matter?

2) Taking account of past ‘over-supply’

Because of the provisions suggested, it is only at the point of plan adoption and then where the housing requirement is out-of-date that an LPA will need to demonstrate a five-year land supply. In the latter case, it will then do so measured against a requirement set by its Local Housing Need. However, the NPPF now proposes that the assessment will need to take account “any previous under or over-supply as set out in planning practice guidance”.

Accounting for oversupply in 5YHLS has been a debate for some time and recognised as a policy gap in the Tewksbury judgment (see my old blog on this case

here). The Government says it wants oversupply in line with that on undersupply. However, this fails to recognise there are two methods of accounting for undersupply: (1) adding on a shortfall to the five-year requirement if the local plan requirement is used (a direct measure); or (2) the affordability uplift in the standard method (an indirect measure).

Given it will only be LPAs with an out-of-date plan that need to demonstrate a 5YHLS, using local housing need (and thus apply the Standard Method or an alternative method that reflects market signals), it might be that the expectation to take account of oversupply has a more direct consequence to the five-year requirement than does undersupply. Fundamentally, however, there is a conceptual flaw in the proposal. Where the standard method is used to estimate the requirement figure, it is set with reference to the affordability ratio, and this is a measure intended to reflect how the past supply of housing impacts on prices. The PPG states

[4] with reference to ‘under supply’ that for the Standard Method there is no need to take account of past under-delivery because “The affordability adjustment is applied to take account of past under-delivery.” Inherent logic suggests the same should hold true for ‘over-supply’ (as any past over-supply ought to moderate any worsening in the affordability ratio and thus dampen the uplift applied – and thus number of homes to be provided) but this logic is rejected by the Government’s proposed changes.

3) Goodbye to buffers all together

It is not only the 20% buffer that’s proposed to go, it is buffers all together: the 5%, 10% and 20% are proposed to be slayed. For those LPAs that do need to demonstrate a 5YHLS this makes it easier to do so. This proposal weakens the 5YHLS test further and will mean that fewer homes are likely to approved and delivered. The rationale for this change is that buffers add complexity, don’t support the plan-led approach, and may “not bring equivalent supply rewards”. It would be interesting to see the evidence for that assertion.

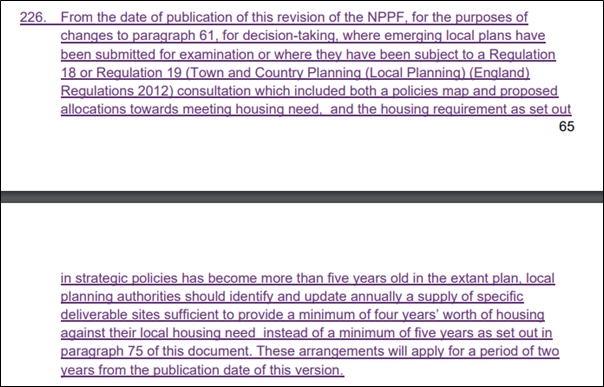

4) How does the four-year supply transitional arrangement work?

Looking back at the Ministerial Statement, I speculated that the proposed four-year supply transitional arrangement might be restricted to those LPAs with specific constraints that would limit their ability to meet housing need. I was wrong.

Upon reading the changes, it applies to any LPA that:

1. Has submitted their plan for examination; or

2. Has a reg.18 or reg.19 plan that has a polices map, specific allocations towards meeting housing need (i.e. potentially not meeting need in full), and a stated housing requirement.

This will apply for two-years from the date of the revised NPPFs publication.

On the ground, this will afford protections to a large number of LPAs without an up-to-date plan but with emerging plans which may have limited detail, may be flawed in terms of soundness, and may not be adopted for some years to come. Albeit I suspect some of these LPA that benefit from this – especially those heavily restricted by Green Belt – may still be unable to demonstrate a four-year supply measured against Local Housing Need.

The timeframe of two years also seems to be a bridging gap for these LPAs. Two years is probably an insufficient time to rework an emerging plan (i.e. amending it based on the new NPPF), consult upon those changes, and get it both examined and adopted. Moreover, there may well be a reworked planning system towards the end of this period with a new local plans process. Therefore, it is probably reasonable to suspect there will be future transitional arrangements.

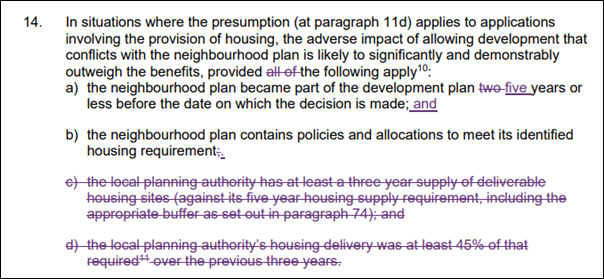

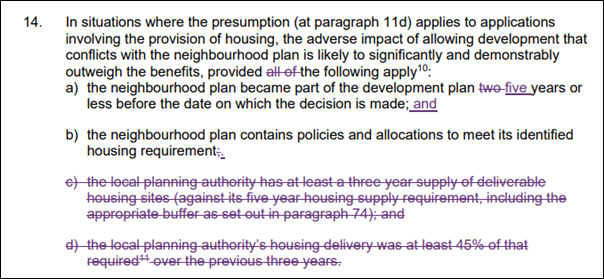

5) Neighbour Plan protections: all powerful

The changes proposed really do add some clout to the protections afforded to Neighbourhood Plans (‘NP’). In effect NPs are treated the same as Local Plans in the context of 5YHLS. This means that an area with an NP with policies and allocations to meet its housing requirements is almost always likely to be protected from a 5YHLS challenge for five years from adoption.

Anything else?

Anything else?One consequential change related to 5YHLS will be an amended process for Annual Position Statements. The uptake of these has been pretty low – only two were received last year by PINS – but presumably an LPA will be able to prepare one once their plan becomes more than five-years old (having not been reviewed and found not to need updating). Arguably though there is not much point to APSs under the wider proposals.

Conclusions

Overall, the conclusions I reached in December haven’t changed. If adopted as one package, we may well see both more plan making and more LPAs being able to demonstrate a 5YHLS (or a four-year supply, or be immune from challenge), but with the corollary that fewer homes will be planned and built.

Reflecting back on the 6th December pronouncements, the draft NPPF wording probably means even fewer homes are likely to be built than I had speculated might be the case when I read the WMS. The five-year protection to local plans with unchallengeable extension despite only having developable sites, the removal of all buffers, the wide range of LPAs that will be afforded a four-year supply transitional arrangements, and the new protections to Neighbourhood Plan areas will all grind away at any scope to address shortfalls in delivery in the places that, arguably, will need the homes most.

[1] The NPPF states “To be considered developable, sites should be in a suitable location for housing development with a reasonable prospect that they will be available and could be viably developed at the point envisaged”

[2] Reigate and Banstead and Woking are good examples – See Planning Resource here (£)

[3] As detailed in our London focused research ‘Mind the Gap’ – see Figure 8.

[4] PPG ID: 2a-011-20190220

Anything else?

Anything else?