In January 2021, Natural Resources Wales (NRW) introduced new tougher targets and guidance for phosphate pollution in riverine Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) across Wales. The new targets vary according to river characteristic, with maximum allowable concentrations of soluble reactive phosphorus ranging from 10-60 µg l

-1. The majority of previous phosphorus targets were in the range of 20-100 µg l

-1[1].

Phosphates are naturally occurring minerals found in human and animal waste. They are vital for plant growth – hence used in crop fertilisers – but at high concentrations in water bodies phosphates can cause dramatic growth of algae. This leads to depleted oxygen levels in the water which can be detrimental to aquatic plant and animal life. The new phosphate targets seek to alleviate these pressures on Wales’ river systems.

As a result of the new targets, it has become necessary to identify ways in which to ensure that new residential developments do not increase the nutrient load on SACs following discharge from a sewage treatment work. This has resulted in many local planning authorities (LPAs) being unable to determine planning applications for residential development in the riverine SAC catchment areas and Local Development Plan (LDP) preparations are also being stalled or delayed. The consequence of this is that housing delivery in parts of Wales has been adversely affected.

Against this context, the purpose of this blog is to provide an overview of the issue from a planning perspective and to consider the ways in which the impact of the phosphate targets on housing delivery in affected areas can be reduced.

The extent of the issue

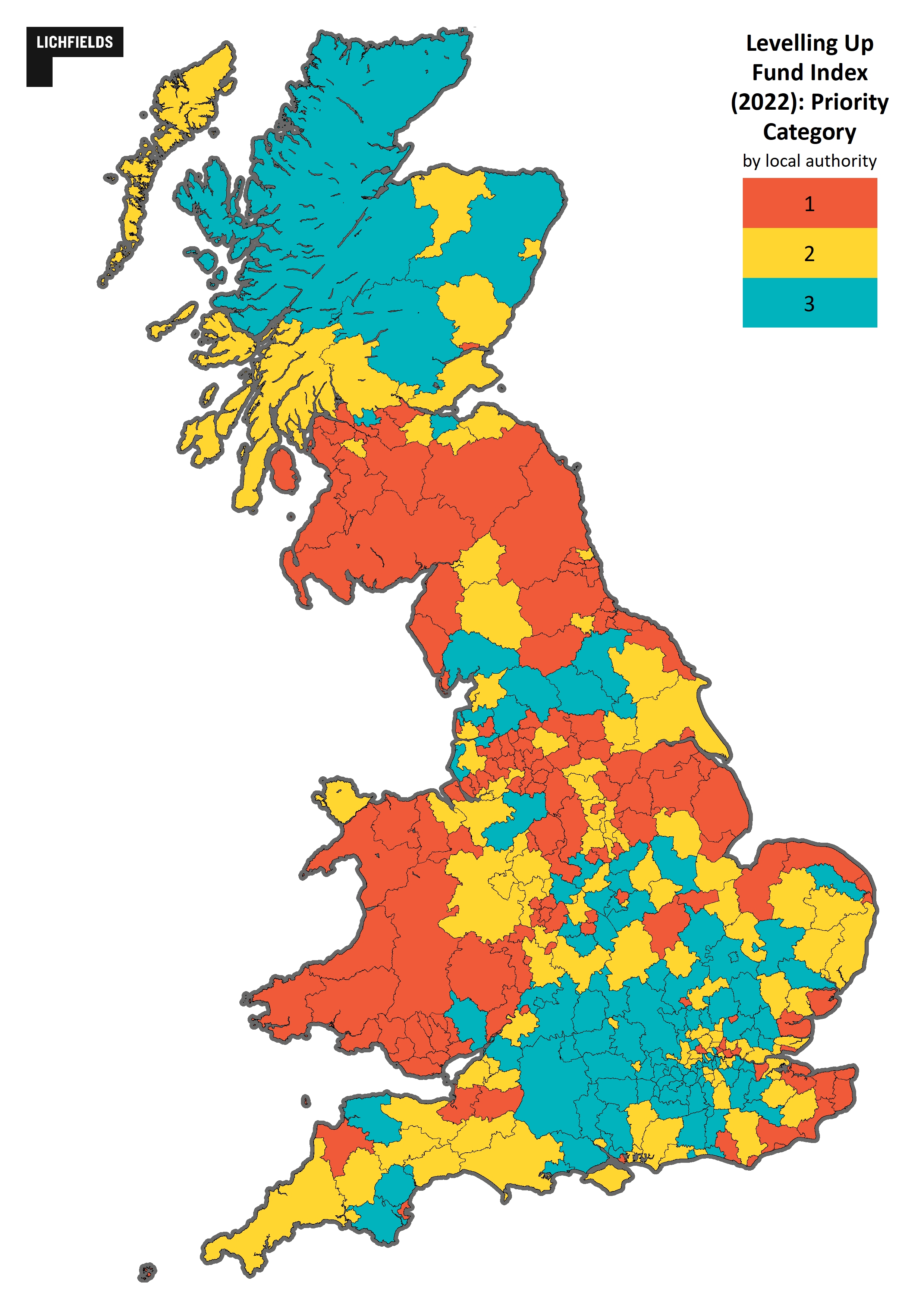

There are nine Riverine SACs in Wales – Cleddau, Eden, Gwyfrai, Teifi, Tywi, Glaslyn, Dee, Usk and Wye – which can be viewed at

DataWalesMap. These SACs are designated to conserve various habitats and species, including rare and threatened species. NRW’s ‘Compliance Assessment of Welsh River SACs against Phosphorus Targets

[2], details that 61% of water bodies tested within the riverine SACs failed to meet their phosphorus targets. In areas where current levels are problematic, for example the River Usk SAC where 88% of water bodies failed to meet their phosphate targets, then there is likely to be greater resistance to residential development.

The map below shows which LPAs have a Riverine SAC within their area. Of the 22 LPAs in Wales (25 including National Park Authorities (NPAs)), 12 LPAs (14 including NPAs) are affected by the new phosphate targets. These account for 84.1%

[3] of Wales by area and 44.7%

[4] of the Welsh population.

Lichfields Commentary: Why are the phosphate targets causing housing delivery to slow?

As set out above, the NRW targets means that proposals for residential development within Riverine SAC areas must now demonstrate it will not contribute to increased phosphate levels within the SAC (i.e. they must be phosphate neutral or negative when compared to nutrient levels associated with the current use of the land). Whether the site is allocated for development in the LPA’s Local Plan is irrelevant.

Guidance issued to LPAs by NRW

[5] states that every development should be considered on a case by case basis and developments should first be screened to determine whether they are likely to have a significant effect on phosphate levels. Developments that do not increase the volume of foul waste water, reduce the phosphorus load of water or decrease the volume of wastewater produced can be screened out – but very few developments are likely to meet these criteria. A fundamental issue arising is how to assess the nutrient load associated with development. NRW has not provided a calculator that can be used by developers and LPAs to calculate the level of phosphates developments will generate. This unhelpfully means that it is not currently possible to assess whether proposals would contribute to increased phosphate levels and thereby meet the targets that NRW has established.

Until developers and LPAs are able to quantitatively assess and provide mitigation for phosphates levels, many LPAs are not able to determine planning applications for housing in riverine SAC areas. This is especially true where housing and other developments propose to connect to an existing wastewater treatment works as even if these treatment works do have phosphate stripping facilities, it cannot be assumed that this will be sufficient to guarantee phosphate neutrality.

There are even longer-term implications of the targets, including significant delays in LDP preparations. For example, in January 2022 Pembrokeshire County Council announced delays to the LDP timetable including a return to the Deposit Plan stage because the LPA does not know which candidate sites located within Riverine SACs can be retained in the Plan

[6]. The new timetable for the LDP is still uncertain as it is dependent on the outcomes of research that itself cannot take place until further guidance for measuring and mitigating the impact of phosphates levels is available.

This is not a problem that is unique to Pembrokeshire; the emerging Flintshire LDP and Wrexham LDP, which are both at latter stages (examination) are also experiencing substantial delays, with Inspectors stating that the new phosphate targets had cast considerable doubts of the viability of housing sites included in the emerging LDPs

[7],[8].

As Welsh Government is highly focussed on LDP-led development and LDPs are being delayed due to the lack of guidance surrounding the new phosphate targets, the delivery of allocated sites will also be delayed. In the meantime, the abolition of the Five-Year Land Supply policy in Wales (see Lichfields blog: TAN 1 – Gone but not forgotten) means that there are no real means by which to encourage or force LPAs to maintain housing supply in advance of LDP reviews and adoption.

What needs to happen now?

Moving forward, LPAs and developers need to have a way of calculating phosphate levels of proposed developments. Carmarthenshire has just published a calculator

[9] and there is a discussion about developing an all Wales calculator. Whilst this has the potential to allow for a meaningful quantification of impacts and for planning applications to move forward, any calculations of phosphate additions or reductions into the SACs need to focus on the actual change in local population arising from new development. For example, the Natural England Nutrient Calculator

[10] applies an additional occupancy rate per dwelling of 2.4 people

[11]. This figure assumes that all new occupiers of new homes will be new to the area – i.e. that 100 new homes will increase the population by 240 people, and generate a consequential increase in nutrient output.

In reality, however, a significant proportion of residents of new homes are local to the area and will not increase the nutrient load: many people move homes within an area and existing households split, for example as grown-up children move out and form new households. A static population still creates the need for new homes and there should not be a requirement to mitigate new homes arising from existing residents as there will be no increase in phosphate loads.

The Natural England and Carmarthenshire calculators are therefore flawed in that they seek mitigation from homes required to meet the needs of the existing population. Lichfields consider that these calculators need to be revised so that mitigation is only sought from housing that meets the needs of net additional population. This is a calculation that can be readily made using population and household projections. Over-estimating the phosphate loads is detrimental to meeting essential housing needs as developers are having unnecessarily to demonstrate significant phosphate betterment and delivery of mitigation that is not required.

The resilience of river ecosystems is of crucial importance to Wales’ future, but we need to absorb the implications of the new targets now and find a way through to avoid a massive under-delivery of housing. A failure to do this could have significant impacts in terms of meeting the need of existing and newly forming households and will also have adverse economic implications. At a time when the economy is trying to bounce back from the shock of COVID and house prices have reached an all-time high we simply cannot afford to let this issue result in a long term reduction in housebuilding rates.

[1] compliance-assessment-of-welsh-sacs-against-phosphorus-targets-final-v10.pdf (cyfoethnaturiol.cymru)

[2] compliance-assessment-of-welsh-sacs-against-phosphorus-targets-final-v10.pdf (cyfoethnaturiol.cymru)

[3] Lichfields’ analysis

[4] https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/query/construct/submit.asp?forward=yes&menuopt=201&subcomp=

[5] Natural Resources Wales / Advice to planning authorities for planning applications affecting phosphorus sensitive river Special Areas of Conservation

[6] Pembrokeshire County Council Local Development Plan Review LDP2 Timetable and Process Update 12/01/2022

[7] https://wrexham-consult.objective.co.uk/portal/examination_library_page

[8] https://www.flintshire.gov.uk/en/Resident/Planning/LDP-Examination-Sub-Pages/Examination-Library.aspx

[9] https://www.carmarthenshire.gov.wales/home/council-services/planning/ecology-advice/new-phosphate-targets/#.Yh92FavP3IU

[10] https://www.push.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Natural-England’s-latest-guidance-on-achieving-nutrient-neutrality-for-new-housing-development-June-2020.pdf

[11] Based on the national average figure taken from the 2011 Census