Northern Powerhouse

Amidst increasing attention on the Northern Powerhouse agenda, Brendan Edwards (economist) and Stephen Morgan-Hyland (spatial planner) of Lichfields Manchester, talk over the concept of the Aviation Powerhouse.

Morgan-Hyland figures that the term ‘Powerhouse’ conjures up an image of combined energy and strength. The blueprint for the Northern Powerhouse is certainly a coalition. It is a united economic voice, working collaboratively to sell the attributes of the Northern Powerhouse to the world to secure a greater share of international investment. It is a brand that allows the North to establish a single identity and compete with a force greater than the sum of its parts.

Credited to former Chancellor and MP for Tatton George Osborne, the over-arching Northern Powerhouse mantra seeks to respond to a longstanding recognition that the North lacks a competitive economic edge. Edwards notes that whilst there is a productivity gap between the Northern Powerhouse and the rest of the UK, there is an opportunity to attract a greater share of domestic and overseas investment. Morgan-Hyland agrees that the objectives are to rebalance the domestic economy and for the Northern Powerhouse to be pivotal in strengthening the fiscal position of the UK, particularly in a post-Brexit world.

Realising the economic benefits that come from a Northern Powerhouse will be dependent on the success of tackling several strategic challenges: inter-connectivity of cities; improved transport infrastructure; strengthened labour market skills; and a transformation of how inward investment is attracted and secured.

Aviation Powerhouse

Whilst there are challenges it must address, the Northern Powerhouse boasts many strengths. One of these is the Aviation Powerhouse.

The Aviation Powerhouse is a cluster of aviation industry in the North, reaching from Liverpool and Humberside up to Newcastle. Each airport has its own role to play in forming and strengthening this economic cluster. And it’s not just about passengers and cargo. The Aviation Powerhouse extends to all aviation activity, including: business aviation; emergency services; manufacturing and maintenance – as well as its associated training facilities, helicopter operations, military support, and recreational flying.

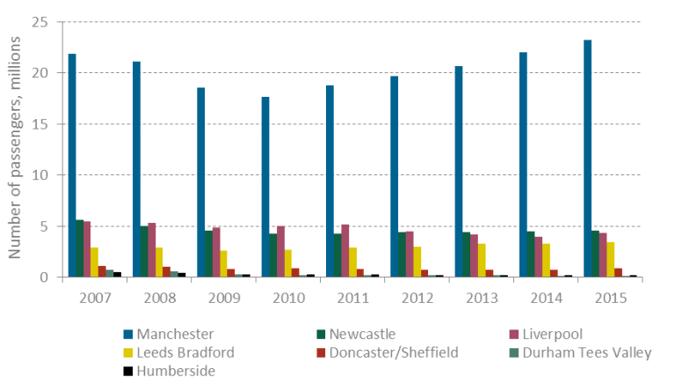

Figure 1: Aviation Powerhouse airports

Source: Lichfields

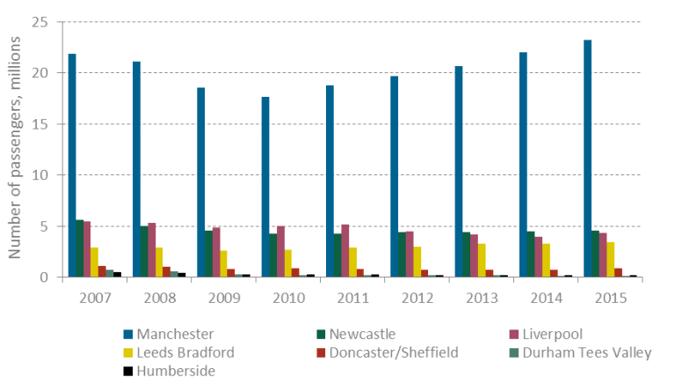

The Aviation Powerhouse boasts seven international airports operating some 500 routes[1] and handling 36.8 million passengers[2]. Morgan-Hyland notes that these combined scheduled passenger numbers put the Aviation Powerhouse on a par with some of the busiest airports in the world.

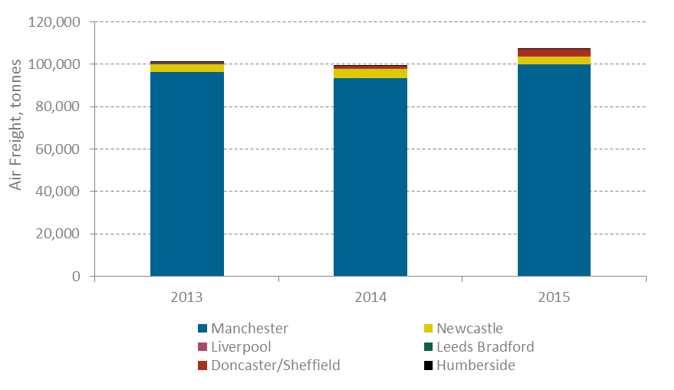

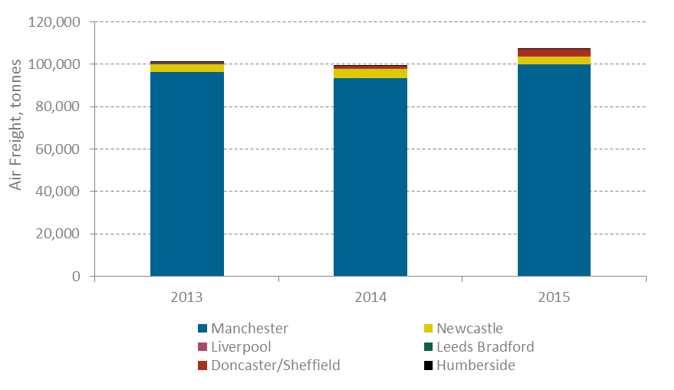

Manchester Airport accounts for nearly two-thirds of scheduled passengers in the Aviation Powerhouse and 85% of the flights to destinations outside of the EU. Newcastle has a transatlantic offer too and the other five airports provide a comprehensive network of EU and UK linkages, including to European global hub airports in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, London, Madrid and Paris. Manchester also accounts for over 90% of freight by volume, whilst the volume of freight handled at Doncaster/Sheffield is growing rapidly; in 2015 it was over 9-times its 2013 levels.

Figure 2: Aviation Powerhouse Passenger Numbers 2017-2015

Source: Airports Commission, Civil Aviation Authority, Lichfields Think Tank

Figure 3: Aviation Powerhouse Freight (Tonnes) 2013-2015

Source: Civil Aviation Authority, Lichfields Think Tank

Economic role of the Aviation Powerhouse

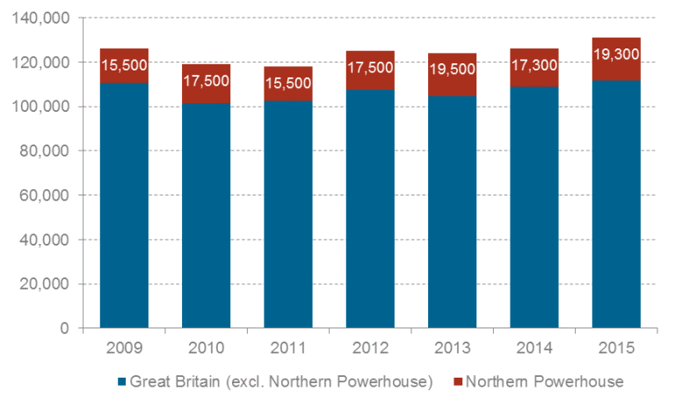

A key point from Edwards is that

the Aviation Powerhouse makes a significant contribution not just to the Northern Powerhouse economy but also to UK plc. In the Northern Powerhouse nearly 20,000 people are directly employed in air transport, supporting services (airport terminals, air traffic control etc.), air cargo handling and warehousing

[3]. Significant additional numbers are indirectly employed and the various airports have made important contributions to inward investments.

Employment in the aviation sector has ‘taken off’ in the Northern Powerhouse; it grew by 24.5% between 2009 and 2015. This is well above the sector’s national growth rate of 4%.

Figure 4: Direct Aviation Sector Employment (2015)

Source: ONS (northern regions), Lichfields Think Tank

Morgan-Hyland adds that the Aviation Powerhouse generates numerous additional jobs through its supply chain spending, aviation manufacturing and tourism. For every job in air transport, 2.32 ‘spin-off’ jobs are created in the economy from supply chain contracts and induced spending

[4].

Aviation also helps businesses to grow by improving connectivity to the global economy and facilitating exports. Further growth in freight handling in the Aviation Powerhouse and improved connectivity to Heathrow (part of the Government proposal for handling capacity in the South East) will improve the competitiveness of businesses in the Northern Powerhouse.

Edwards continues that growth in the Aviation Powerhouse offers the potential to help rebalance the UK’s economy. As well as supporting the growth of Northern Powerhouse businesses, the aviation sector is highly productive. Average GVA per employee in UK air transport services is £87,700 – almost double the average in the Northern Powerhouse and higher than the national average. Further employment growth across the Aviation Powerhouse would help to narrow the productivity gap between the Northern Powerhouse and UK.

Figure 5: Gross Value Added per job (2015 prices)

Source: Oxford Economics, Centre for Cities, Lichfields Think Tank

Morgan-Hyland and Edwards agree that there is clear evidence of the economic benefits resulting from recent growth and success of the Aviation Powerhouse. In addition to experiencing considerable employment growth in recent years, aviation is increasing the output and productivity of the Northern Powerhouse. For example, aviation plays an integral role in ‘Just-in-Time’ manufacturing production, by transporting high value and low volume components and personnel

[5]. This is particularly important for some of the world’s leading car manufacturers; Ford, Jaguar Land Rover and Nissan are all based in the Northern Powerhouse. In return, these benefits can generate positive secondary aviation impact such as additional business growth, employment, and fiscal benefits locally and nationally including revenue for HM Treasury.

The Aviation Powerhouse has significant potential for future expansion in passenger and freight markets, as well as the business aviation and general aviation markets. It has already experienced significant growth in scheduled traffic in recent years. The Aviation Powerhouse is surely a concept for the Northern Powerhouse and the aviation industry to embrace as it drives growth and helps to rebalance the UK economy.

Brendan Edwards is a Senior Economics Consultant and Stephen Morgan-Hyland a Planning Director, at Lichfields Manchester. For more information about Lichfields' expertise in Aviation,

click here.

[1] Lichfields' research based upon published data from the Aviation Powerhouse airports

[2] CAA data for scheduled passenger and commercial flights

[3] ONS, Lichfields Think Tank

[4] Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2014) Employment Multipliers and Effects by Industry

[5] Air Transport Action Group (April 2014) Aviation Benefits Beyond Borders