A year on from the publication of the ‘Building Better, Building Beautiful’ Commission’s report, ‘Living with Beauty’, the Government has issued its response, setting out where it will take forward the Commission’s recommendations. Accompanying the report is a consultation seeking views on the proposed amendments to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the content of the newly published (draft) National Model Design Code and accompanying guidance note.

Launching the changes, the Secretary of State Robert Jenrick commented:

“We should aspire to pass on our heritage to our successors, not depleted but enhanced. In order to do that, we need to bring about a profound and lasting change in the buildings that we build, which is one of the reasons we are placing a greater emphasis on locally popular design, quality and access to nature, through our national planning policies and introducing the National Model Design Codes.”

While the press release and headlines focus on design quality and ‘Beauty’, the revisions to the NPPF cover a broader range of issues, with the Government also consulting on amendments to policies on sustainability, flood risk, and biodiversity; Article 4 Directions; protection of the historic environment; and minor changes which remove now out-of-date references within the Framework.

As the introductory summary states “This is not a wholesale revision of the National Planning Policy Framework, nor does it reflect proposals for wider planning reform set out in the Planning for the Future consultation document”. Taken together, however, the changes are not insignificant; in some areas these point towards possible changes to procedure for plan-making and the determination of applications, alongside a more general tightening of standards.

To get you up to speed with the proposals, we’ve covered the key changes below.

Improving design quality and placemaking

The Government has given centre stage to its proposals to raise the standards of design and quality of new development.

The plan-making section will explicitly promote the “use of masterplans and design codes to secure a variety of well-designed and beautiful homes”. Chapter 12 is to state that all local authorities should implement design codes, the detail of these should be tailored to the circumstances and scale of change in each place. While the current iteration of this policy suggested plans make use visual tools such as design guides and codes, the Government expects these to be more widespread going forward – and integral to improving the quality of new development.

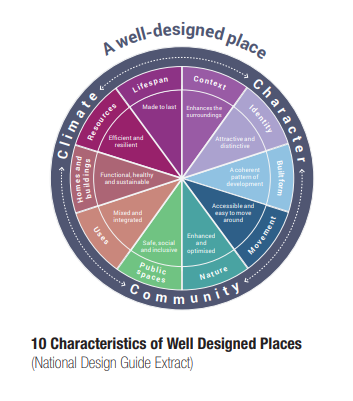

To support this, a (draft) National Model Design Code (NMDC) with an accompanying guidance note has been published. This provides a framework for local authorities to develop their own localised codes; the Department is currently seeking 20 local authorities to run pilots. The NMDC provides a comprehensive list of principles that councils should consider when formulating their own codes, with more detailed definitions and proposed parameters included within the accompanying guidance note.

The state that design codes can be prepared for entire areas, or individual sites, while applicants may also prepare codes for sites which they propose to develop. To carry weight in decision making design codes must be developed in conversation with local communities, in order to reflect local aspirations. Where local codes are absent, the NMDC can be a material consideration.

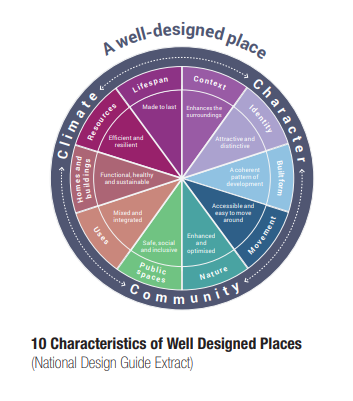

While the word Beauty is used frequently throughout the revised Framework and accompanying guidance, what this means locally will be informed by baseline studies and based on the ‘ten characteristics of a well design place’ as set out in the National Design Guide and expanded upon within the draft NMDC. These bring together a range of established urban design principles such as built form (density, height and layout), movement, identity and public space which are to guide the development of local design criteria. As to the degree of detail that codes should include, the NPPF is to state that codes should “allow a suitable degree of variety where this would be justified”.

The Framework’s policy for encouraging good design is also to be strengthened, with significant weight to be given to development that reflects guidance and policies and outstanding or innovative designs that “fit in with the overall form and layout of their surroundings”. While this is not quite the “fast-track for beauty” put forward in the recent White Paper, the Government has stated in its response to the BBBBC report, that it wishes to explore widening the nature of permitted development, “so that it enables popular and replicable forms of development to be approved easily and quickly”.

The amendments also call for development proposals that are not well-designed to be refused. This is slightly stronger wording than at present, with the Framework currently stating that permission should be refused for development of “poor design” that does not reflect local design standards or codes.

Further to this, the Government proposes to take forward the Building Better Commission’s proposals for streets to be lined with trees; “unless, in specific cases, there are clear, justifiable and compelling reasons why this would be inappropriate”. Furthermore, opportunities should be taken to retain trees and/or incorporate trees elsewhere in developments. There should also be measures to ensure that trees are maintained post completion; it seems that this would likely be through conditions.

Achieving sustainable development: Global Goals, biodiversity, flood risk and protected landscapes

Amendments have been proposed to paragraph 11 (a), regarding the ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’; plan-makers will be required to “align growth and infrastructure; improve the environment; mitigate climate change (including by making effective use of land in urban areas) and adapt to its effects”. It would appear that the proposed changes seek to adapt this objective so that it would respond to areas of concern raised by Tory backbenchers in recent months, particularly regarding the delivery of infrastructure provision for new housing and focusing development on brownfield sites.

The Framework now also makes reference to the United Nation’s 17 Global Goals for Sustainable Development under paragraph 7, part of the Government’s strategy to ensure that the objectives (which the Government signed up to in 2015) are embedded in the planned activities of each Government department.

There have been some changes to the policies on biodiversity, with paragraph 178 having been amended so that development primarily aimed at conserving or enhancing biodiversity should be supported. Further to this, improvements to biodiversity in and around other types development should recognise opportunities to “enhance public access to nature”.

On flood risk, draft paragraph 160 (currently paragraph 156) has been amended to clarify the sequential test should take into account all potential sources of flood risk. Further to this, the Flood Risk Vulnerability Classification is now included within the NPPF under Annex 3, moving from guidance to .

Changes are also proposed in light of the recent Glover Review of protected landscapes. The proposed changes would seek to ensure that the scale and extent of development within the ‘settings’ of National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (not only within, as at present) should be sensitively located and designed so as to avoid adverse impacts on the designated landscapes.

Decision making: Article 4 directions and permitted development for residential use

Interestingly, the Government has sought to tighten the considerations to be applied when deciding if it is expedient to introduce for

Article 4 Directions (i.e. areas where certain permitted development rights do not apply)

[1].

It is proposed that all Article 4 Directions are limited to “the smallest geographical area possible”, but the amendments also seek to distinguish between the considerations for when it might be appropriate to remove permitted development rights for changes of use to residential and instances to remove other permitted development rights.

The Government has proposed policy that would apply only to change of use to residential, with two possible wordings - either that these rights will only be acceptable in “situations where this is essential to avoid wholly unacceptable adverse impacts”. or “where this is necessary in order to protect an interest of national significance”.

This pre-empts proposals for authority-wide removal of the new Permitted Development right for converting the new Use Class E (commercial, business and services) to C3 residential, which was proposed in December.

As noted above, the Government says it wishes to explore widening the nature of permitted development further, and the proposed amendments regarding Article 4 Direction are a nod to this future intention too.

With the changes to Use Classes Order having cast doubt over the potential effectiveness of some existing Article 4 Directions (by virtue of former use Class B1 now being subsumed into the new use class E), it is not yet clear what the status of existing Article 4 directions will be, or whether any future changes to the GPDO will include transitional arrangements.

Heritage and protections for statues

Chapter 16 of the Framework,

Conserving and enhancing the historic environment, is to have a new paragraph 197 relating to the preservation of historic statues and related, following concerns from the Government that these were being removed “

without proper debate, consultation with the public and due process”.

The new paragraph states:

In considering any applications to remove or alter a historic statue, plaque or memorial (whether listed or not), local planning authorities should have regard to the importance of retaining these heritage assets and, where appropriate, of explaining their historic and social context rather than removal.

This policy seems intended to accompany changes to the law which were announced by the SoS in a

press release on 17 January 2021. These proposed that where a council intended to grant planning permission for works involving the removal of any statues or statutory listed objects, the Communities Secretary would be notified and would take the final decision.

More broadly, the preservation and enhancement of the historic built environment underpins much of the Government’s ‘building beautiful’ agenda; with the National Model Design Code supporting the use of character appraisals and heritage assessments to form the baseline for the development of design codes.

Concluding thoughts

It is encouraging to see the Government placing greater importance on delivering well designed, sustainable development; most in the sector will agree with the sentiment of the proposals at least. While the immediate draft changes may be limited in effect, the proposals do amount to a notable shift in how the Government require the design of new developments to be assessed, particularly if design codes are to be used more widely, and the importance of design quality.

Such a change will no doubt cause some practical transitional difficulties, as councils, developers and local communities grapple with the creation of new codes and procedures , how these are interpreted and applied and whether flexibility should be applied for proposals that fail to accord with certain aspects of a local design code.

Next steps

To support the Government in its aims, a Written Statement made by the SoS on 1 February 2021, advised;

“We will be establishing an interim Office for Place within the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, with a transition board chaired by Nicholas Boys Smith tasked with considering what form the organisation should take, informed by responses to the “Planning for the Future” consultation.”

With the Building Better Commission having identified a skills gap in many authorities, ensuring authorities are equipped to deal with the changes will be key to ensuring design codes are successfully adopted and achieve their stated aims.

The consultation will run until 27 March 2021. These changes are intended to be short term amendments, with the Government also indicating that a comprehensive review of the Framework is likely, ‘depending on the implementation of the government’s proposals for wider reform of the planning system’.

[1] Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015 says:

“If the Secretary of State or the local planning authority is satisfied that it is expedient that development described in any Part, Class or paragraph in Schedule 2, other than Class DA of Part 4 or Class K, KA or M of Part 17, should not be carried out unless permission is granted for it on an application, the Secretary of State or (as the case may be) the local planning authority, may make a direction under this paragraph that the permission granted by article 3 does not apply to -

(a) all or any development of the Part, Class or paragraph in question in an area specified in the direction; or

(b) any particular development, falling within that Part, Class or paragraph, which is specified in the direction,

and the direction must specify that it is made under this paragraph”