The proposed changes to the NPPF

[1] will have a significant impact on house building. The Government accompanied its launch of the consultation in December with the statement that:

“The government remains committed to delivering 300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s and many of the immediate changes focus on how we plan to deliver the homes our communities need. We know that the best way to secure more high-quality homes in the right places is through the adoption of local plans".

The Government contends that the proposals will support housebuilding because it will encourage local plans to be prepared

[2]. However,

analysis by Lichfields for the HBF and LPDF finds that the policy proposals on their own could suppress the rate of net additional homes to just 156k per annum. Even before one factors in issues like the economic downturn or water and nutrient neutrality barriers to house building

[3], this would mean building around half of the Government’s assessment of minimum housing need and 77k less than recent rates of delivery.

This is the first of two blogs exploring the implications of the draft NPPF for housing supply and the consequences flowing from that. This first blog explains why the proposals are likely to have such a negative effect on housebuilding and what this would mean for the economy. The

second blog looks at the societal consequences.

Why will the NPPF proposals act to reduce housing supply?

The planning system typically rations the amount of land (brownfield or greenfield) allocated for new homes in each area based on what is considered necessary to meet the local housing requirement (or target) set by strategic and local plans. Local targets are set with reference to the number of homes estimated by the Government’s standard method for housing need plus any unmet housing need from neighbouring areas.

Areas can moderate their target based on constraints (e.g. environmental) in their area, where consistent with national policy. They can also increase their target if they wish – such as in response to Growth deals – but this is not widespread, and seemingly declining

[4].

National policy provides a ‘stick’ to try and correct for any under-supply by enabling developers to bring forward proposals not in accordance with the Local Plan and have them determined against the presumption in favour of sustainable development (the so-called ‘tilted balance’) in circumstances where a local plan is out of date, a planning authority cannot demonstrate a five year land supply and/or if it fails the housing delivery test.

Combined, this means the number of homes built in each area will be heavily influenced by:

a. Its local housing need figure based on the standard method;

b. how far the local plan housing target meets the local housing need plus any unmet housing need from neighbouring areas; and

c. how far the ‘stick’ mechanisms enable new supply to come forward if a local plan is absent or if a local plan’s strategy for housing turns out not to be effective.

Progress towards the national 300k ambition therefore depends on an aggregation of what happens in each area – with different land use circumstances – in response to its local housing need and the planning ‘rules’ set by national policy. This is not new: the benchmark rate of housing required used in the Housing Delivery Test reflects how the system has responded to the 2012 and 2018 iterations of the NPPF and it adds up to about 230-240k per annum over recent years, well short of the 300K required, but very similar to the amount of housing that has actually been supplied (albeit with some areas doing more, and some doing less). Yes, the market cycle has an effect and there are ups and downs, but ultimately house builder land pipelines have to respond to the anticipated run rate at which new sites are expected to become available via planning, as

research found in 2021.

The Government’s proposed changes to national policy have not changed the estimate of housing need (albeit the combined local housing need outputs add up to ever so slightly under 300k), but they would change the planning rules. Our assessment identifies five core factors that will lead to the 77k reduction in housing supply, as illustrated below:

Each reduction is explained below:

- London’s housing need under the standard method is 86k homes per annum. The adopted London Plan sets a target of 52k based on evidence that realistic supply of land is limited in the capital[5]. The high point of housing delivery in the capital was 41k in 2019/20 but the recent average is 37.4k. The proposed changes to the NPPF now specifically resist building at densities significantly out of character with the existing area[6], which will limit many forms of development that have driven higher output; supply is unlikely to exceed the recent average, let alone increase to drive supply up towards the London Plan target of 52k, with zero prospect of meeting need at 86k[7].

- The 19 other large urban centres are subject to the 35% uplift in the standard method and the NPPF proposals indicate this should be accommodated within those cities themselves[8] with removal of the expectation that unmet need should be accommodated in neighbouring areas[9]. There is widespread recognition[10] that these cities do not have sufficient brownfield capacity, many are surrounded by Green Belt or administratively tightly bounded, and the NPPF proposals on character will – as in London – limit densification proposals, particularly in suburbs. Many have been building out existing housing allocations (including on previous Green Belt releases) that are now unlikely to be replaced. We conclude these areas will undershoot their housing need by 19.6k.

- There are 108 local authority areas where the amount of land constrained by urban footprint, Green Belt and other designations under Footnote 7 of the NPPF acts to limit the availability of land for development. Since 2012, plan makers interpreted national policy as requiring them to review the Green Belt to see if some of it can be released for development to address housing needs[11]; such areas have also tried to optimise density on previously developed sites and, if there was unmet need, to try and ensure any unmet need is addressed in neighbouring areas. All three of these policy obligations are removed or diluted by the NPPF proposals. This means there is no realistic prospect of housing need being met in these areas; in fact, rates of housebuilding are likely to reduce as readily deliverable brownfield capacity is exhausted, densities are lowered for character reasons, and Green Belt releases are built out and not replaced. We conclude these areas will under-shoot their housing need by 30.4k.

- Some areas have built more than their adopted housing targets, so called ‘over-delivery’. Although the NPPF says that the standard method is a ‘minimum number’, the proposed amendment (Para 11 b) iii.) says that ‘over-delivery’ may be deducted from the provision required in the plan. Precisely how this will apply awaits guidance, but it will obviously have some effect in those areas that have been successful in housebuilding. We conservatively suggest they will under-shoot their housing need by 3.6k. This clause also means that areas that do more than their targets in future will be able to offset it against future need.

- Finally, the NPPF proposes to reduce the expectations for maintaining a five-year land supply and operation of the Housing Delivery Test (HDT)[12]. This flows from the removal of the buffer; from those with a Reg 18 plan only needing a four-year supply; from those with an adopted plan not needing to maintain a five-year supply at all until the plan is out of date; from Neighbourhood Plans conferring 'protection' for five years instead of two; and from there being little consequence of failing the HDT. The combined impacts on supply are uncertain, but it will inevitably reduce significantly the circumstances whereby permissions for housing are granted in order to mitigate existing or future shortfalls in housing land supply.

Last year, some 26,813 homes were granted approval at appeal[13], and many more will have been approved directly by local authorities because they conclude they do not have – or might in future not have – a five-year land supply. A January 2023 survey by Planning Magazine (available here [£]), found that 38% of local authorities report they do not have a five year housing land supply, with scores of LPAs in the band of reporting 4-6 years supply, who may now find themselves 'protected'. Further, planning appeal decisions routinely find that the five-year land supply positions of local authorities turn out to be lower than originally estimated. Research on the accuracy of five-year land supply trajectories showed that the average over-estimation of housing output by London Boroughs in year 1 of their trajectory was 20%, with accuracy then deteriorating further for subsequent years[14]. Discount rates of 10% are routinely applied in five-year land supply assessments, and evidence in Milton Keynes found that an optimism bias that over-estimated supply in the order of 10-25%[15]. In future, with no requirement to demonstrate a five-year land supply once a local plan is adopted, and reduced consequences of failing the HDT, there will be less pressure on local authorities to exercise their role as enablers of housing delivery[16]. This will inevitably increase the level of optimism bias on site output[17]. We conclude a reduced output of 38k (broadly equivalent to c.20% of the residual housing delivery after the other deductions) to reflect a reduction in the housing granted at appeal, less pressure on Councils to grant applications in order to protect their land supply position, and increased optimism bias in five-year land supply trajectories.

The above comes on top of the immediate effects on supply of the economic and housing market downturn, and of course the significant number of homes (estimated at over 100,000) being held up by water and nutrient neutrality barriers across 75 local authority areas.

We do not find measures in the proposed NPPF changes that would suggest housing output will increase or counter the prevailing downward pressures. Even if the Government is correct that more local plans will be prepared, fewer of them are likely to have targets that meet their local housing need or address unmet need from neighbours, and there will be fewer measures to address the inevitable shortfalls in housing delivery that follow. Future LURB proposals – e.g. on street votes – are some way off and even if they deliver on their promise, they are unlikely to move the dial on actual delivery in the short to medium term.

What are the implications of reduced housebuilding?

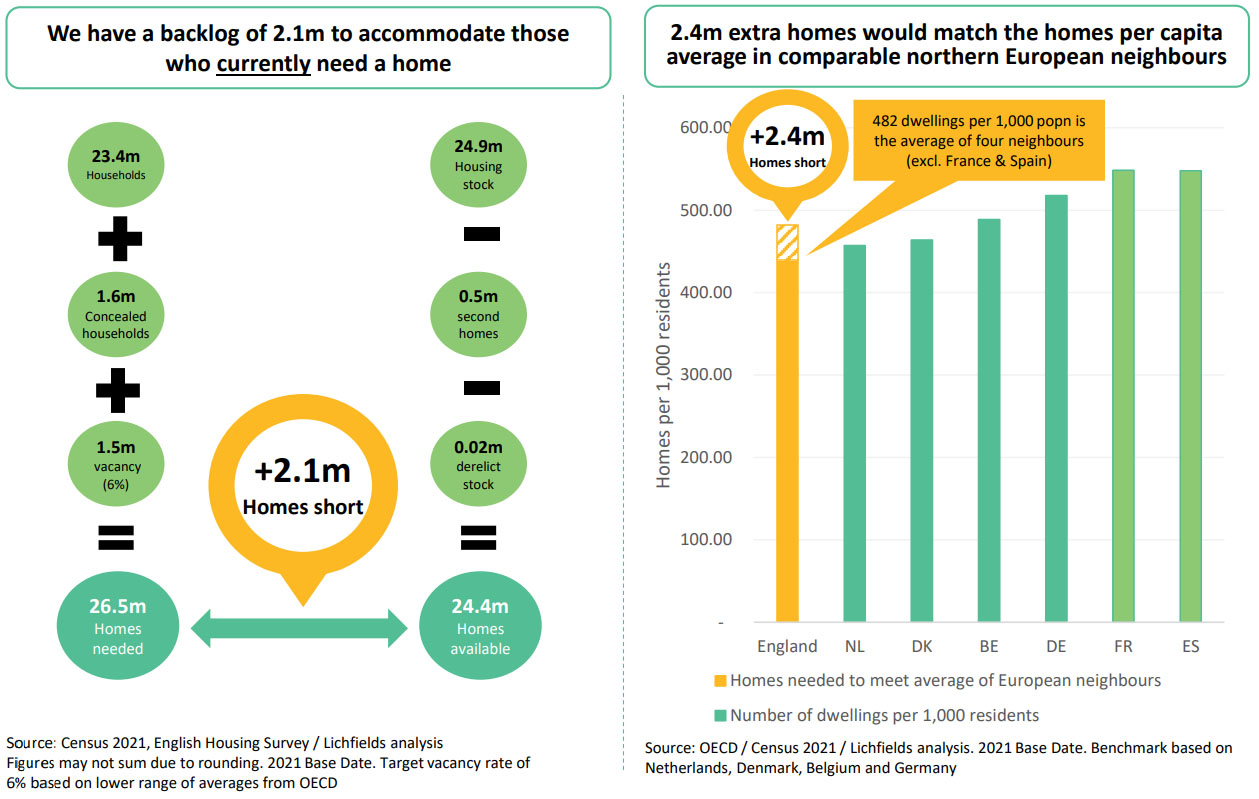

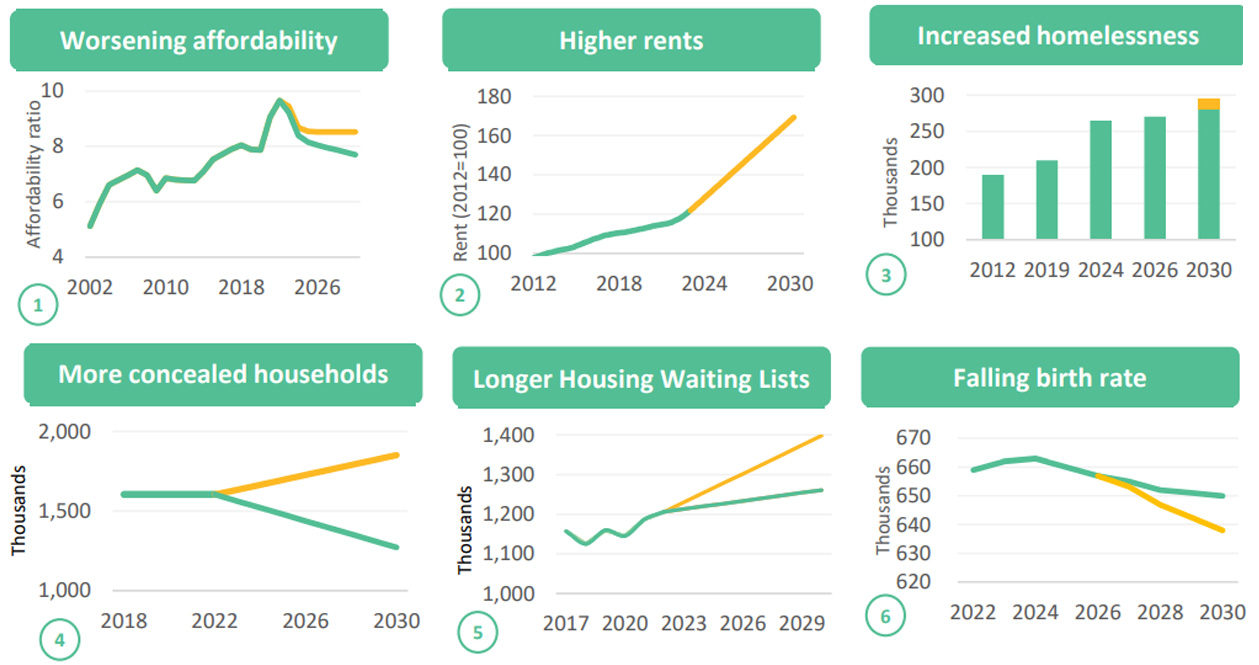

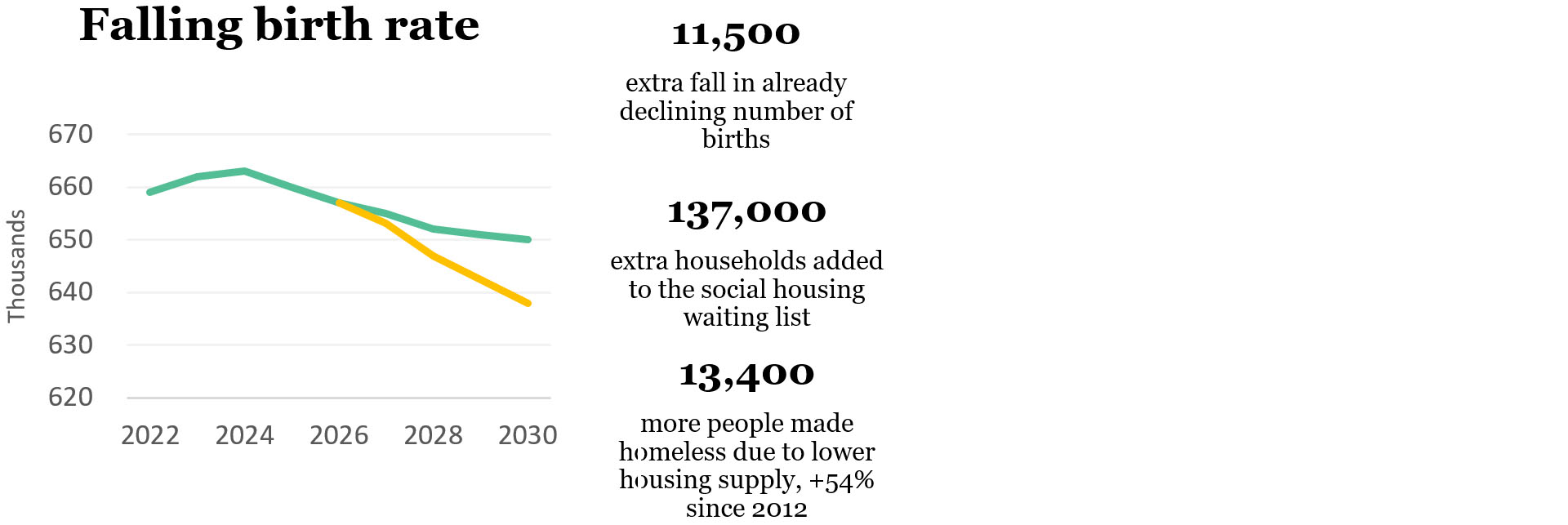

Housing has an obvious role in providing people with accommodation to buy and rent. Our analysis suggests the downward pressure will be in areas where this is most needed: more than half of the shortfall against the 300k ambition will be in the least affordable third of local authorities. We will address some of the societal implications of this in our next blog. Here we focus on the cost to the economy.

Direct economic implications

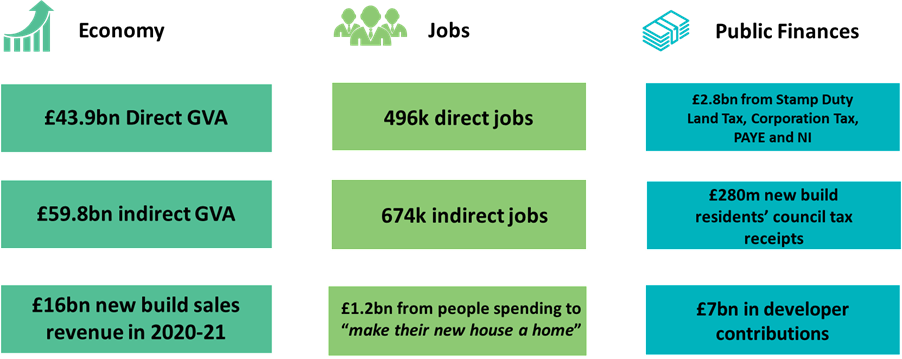

The house-building industry is a major driver of economic growth and supports sustainable local communities

[18]. The introduction to the Barker Review

[19] found that:

“A weak supply of housing contributes to macroeconomic instability and hinders labour market flexibility, constraining economic growth”While the latest economic figures show that the UK is not technically in recession, the cost of living crisis and slow growth rates have put sharp focus on the levers available to Government to help stimulate an economy so that it that provides well paid jobs and boosts tax revenue to pay for stretched public services.

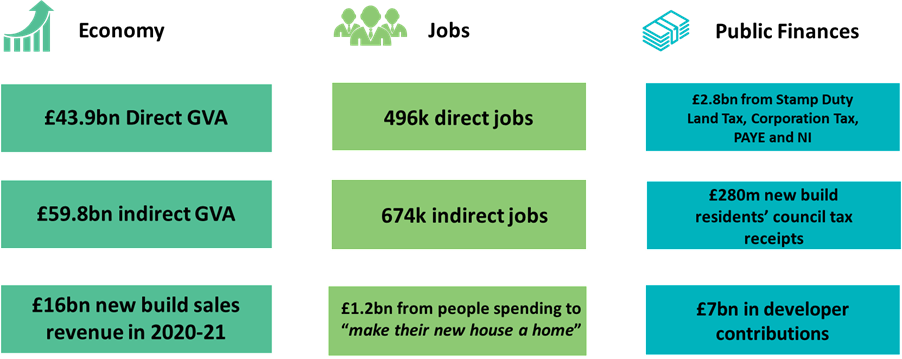

Source: Lichfields analysis drawing on HBF (2018) The Economic Footprint of Housebuilding. Applied to 2021 total housing supply. New build revenue from latest UKHPI. Council Tax from VOA data in 2021-22. First occupation expenditure uses average estimated amount in OnePoll in 2014. Tax Value is prorated from survey of housebuilders in 2016-17 for HBF report. Developer contributions figure from 2020 MHLGC commissioned research.

Our estimate is that – directly and indirectly - housebuilding contributes £104bn to the economy each year, supporting 1.2m jobs and generating £3.1bn of tax income. Additionally, house builders make £7bn in extra contributions (through Section 106 and Community Infrastructure payments) to help fund infrastructure, social housing and open spaces.

However, if the proposed changes to the NPPF are implemented and the number of new homes added each year is reduced to 156k, the cost to the economy will be significant. £70bn rather than £104bn of GVA, and 784k jobs rather than 1.2m jobs. To put it another way, compared to now, the proposed changes could cost £34bn of GVA and 386k jobs. There will be consequential reductions in tax revenue.

In reality, in combination with the impact of water and nitrate neutrality restrictions, the economic footprint could decline even further.

Of course, the opposite is also true, a set of NPPF policy measures that supported the meeting of housing need at 300k per annum would almost double the footprint from that likely to arise from the proposed changes, to around £134bn of GVA and 1.5m jobs.

The indirect economic impact of under delivery

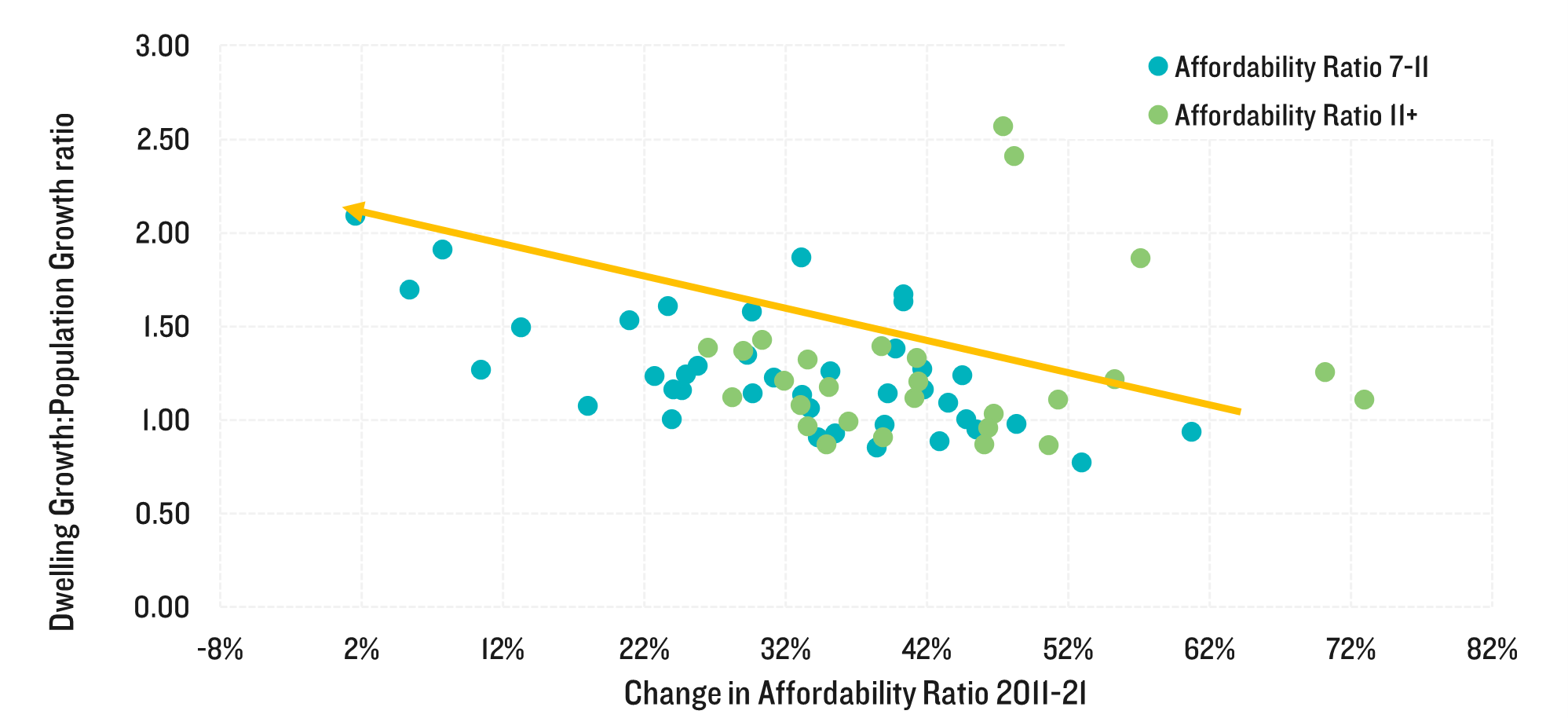

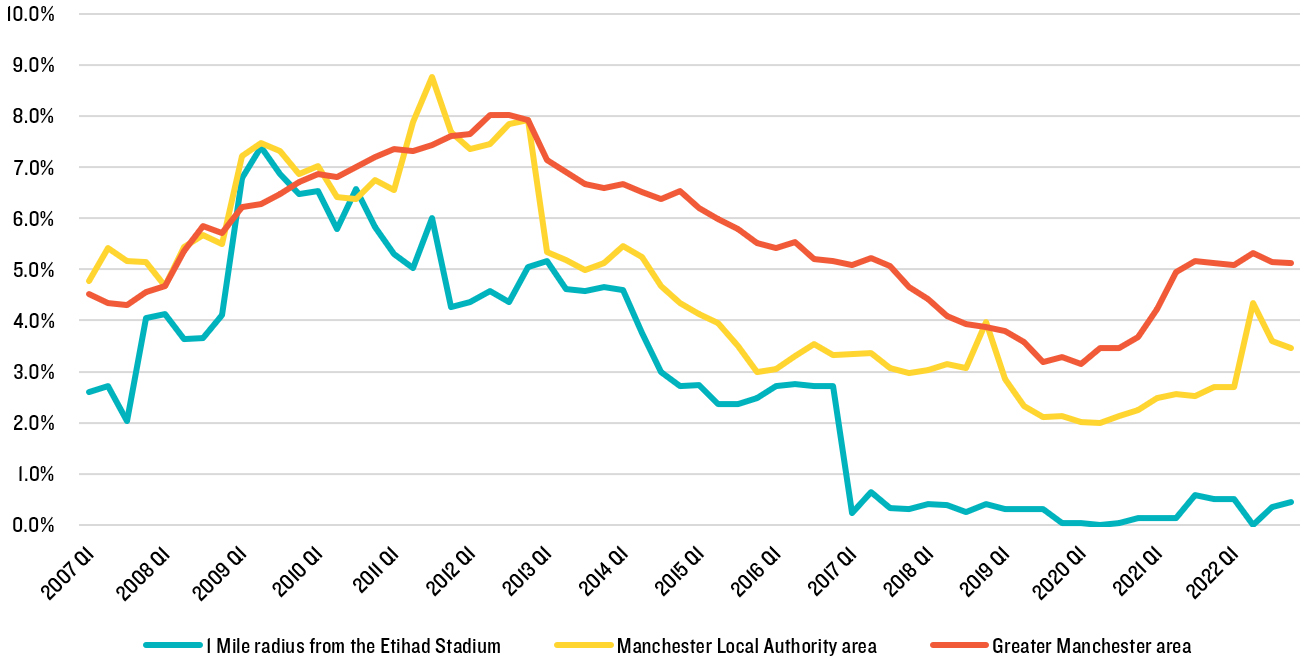

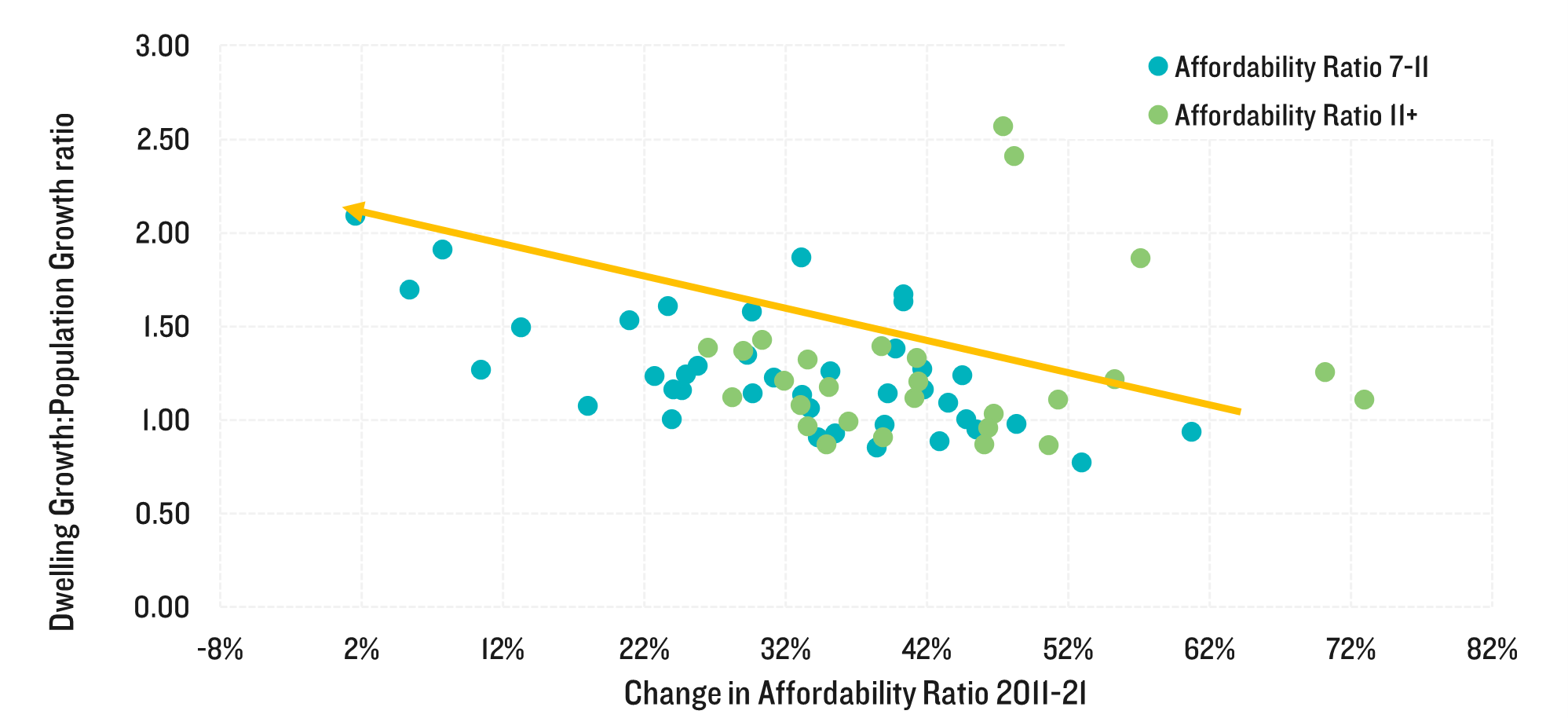

Boosting supply over the long term helps make homes more affordable

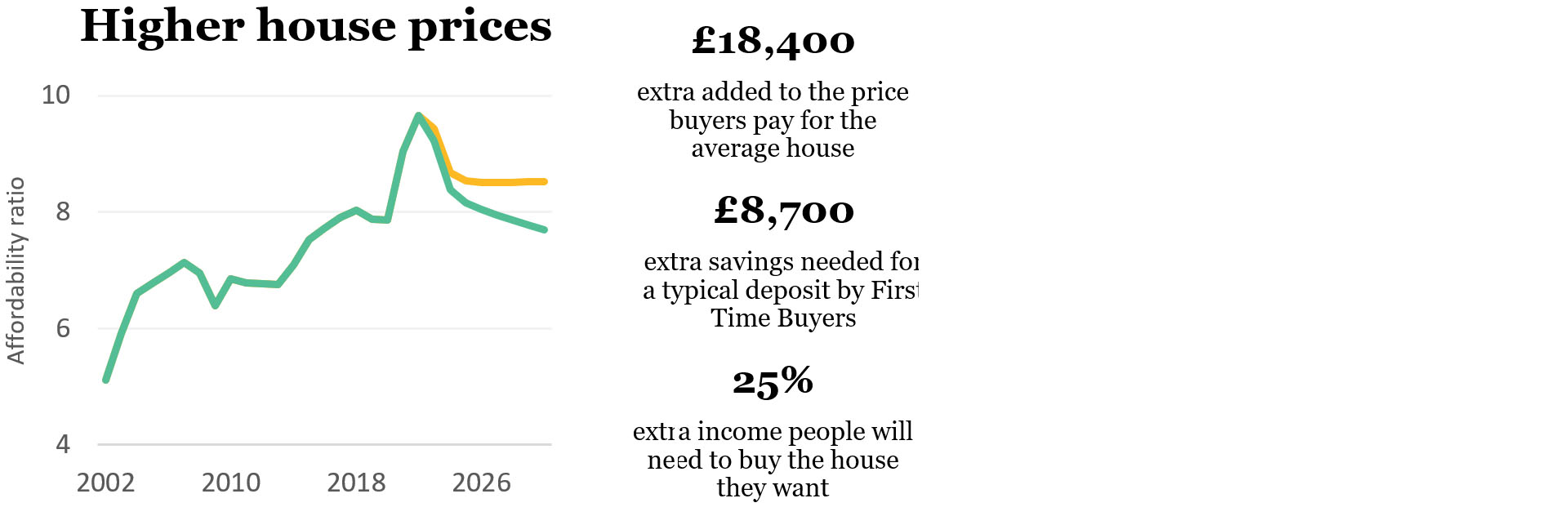

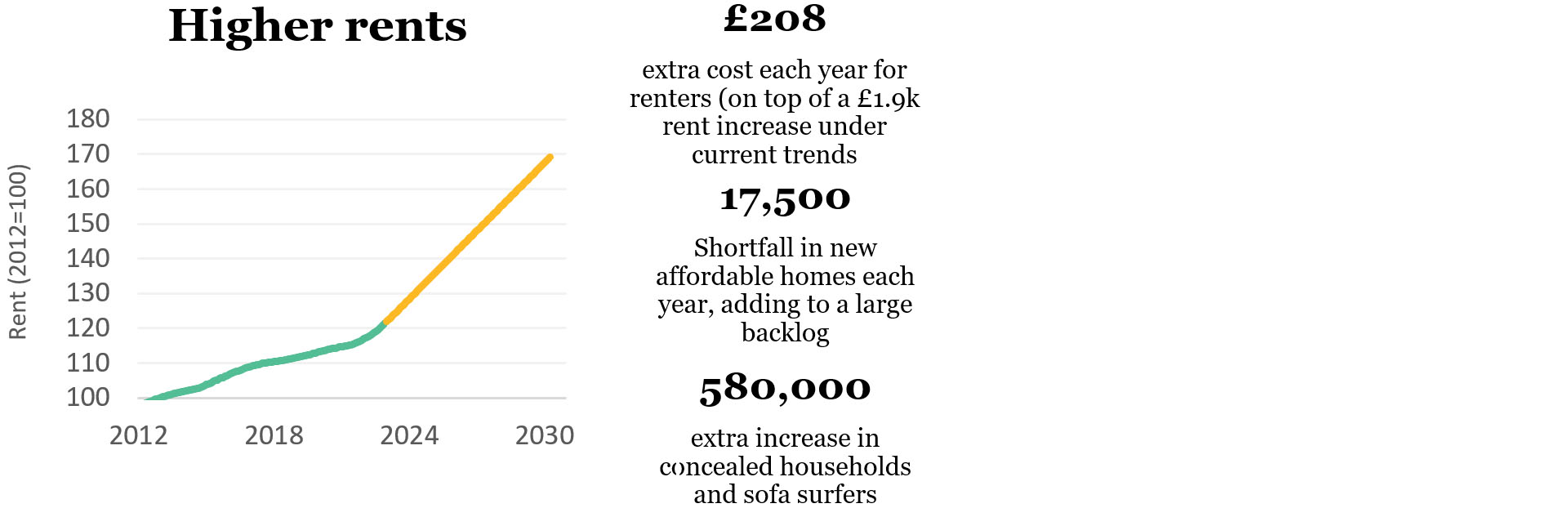

[20]. Analysis by Lichfields of affordability, rates of house building, and population change 2011-2021 shows a positive correlation in the least affordable housing markets between building more (relative to population growth) and relative improvements in rates of affordability.

In the least affordable areas, when housebuilding exceeds population growth, relative affordability improves between 2011-2021

In the absence of building sufficient homes, prices will instead continue to rise. The lack of homes in England’s most economically successful areas, such as Oxford, Cambridge and London, already locks people out of opportunities in the most productive places, undermining both social mobility and the potential agglomeration gains to key industries of co-location. Knowledge-based workers with the ability to secure high quality jobs anywhere in the world will be more likely to vote with their feet in search of places where their money goes further. And with access to skilled labour a more valuable commodity in the knowledge economy, globally mobile firms will be more likely to direct investment overseas. The macro effect will undermine Levelling Up missions for productivity.

The lack of house building, and restricted land supply is harming productivity. The Economist recently reported

[21] that land went from taking up 39% of the value of non financial assets in 1995 to 56% in 2020 in Britain. This means land - and housing - soaks up investment, ‘crowding out’ more economically productive alternatives to which banks can lend and for investors to see returns. In 2022

. Those who cannot afford to own a home miss out, and spend more income on ever-rising rents. Recent

Lichfields research for Barratt found those renting in northern and midland Core City regions who could reasonably expect to buy but for high deposits will lose out a total of £945m in lost savings and equity over the next ten years.

These high and rising house prices also exclude key workers from our most economically successful places, harming not only these individuals but the sustainability, vitality and resilience of whole areas. Those such as nurses, teachers, NHS cleaners, and community support officers are being priced out of areas that need them most. 2018 research by Unison

found that key public sector workers need to save between 5% and 7% of gross pay for more than 30 years just to afford the average deposit. Recruitment is a key barrier to Levelling Up missions for education, health and crime

[24].

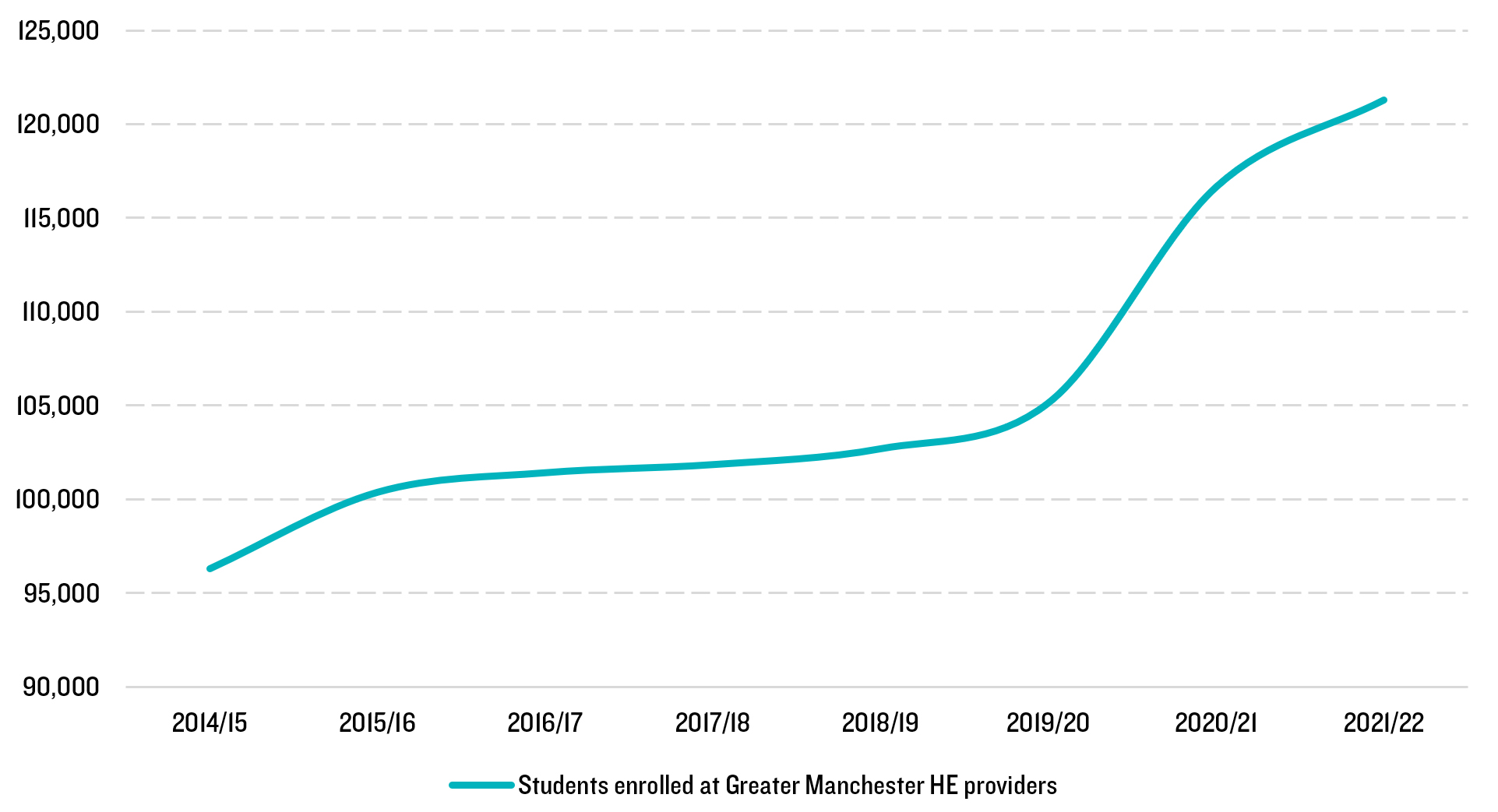

In addition, businesses are struggling to find the space to grow. The 20 cities that have had their local housing need figures boosted by the 35% urban centres uplift account for 40% of England’s productivity (GVA). The increased pressure the proposed changes to the NPPF places on meeting this need within those local authorities and without impacting on the prevailing character of existing residential areas will increase pressure on local authorities to re-allocate land away from industrial space

[25]; many cities are also losing their much-needed employment space to housing and this will worsen under the proposals. Since 2000 London lost a quarter (24%) Greater Manchester 20% and the West Midlands 19% of industrial floorspace to housing.

[26]

Conclusion

England suffers from unaffordable housing due in large part to a lack of sufficient house building over a sustained period. The 300k ambition was a policy drive aimed at reversing this structural problem. Unfortunately, our assessment is that the latest proposed NPPF reforms threaten to make what is a bad situation even worse, taking supply down by 77k to just 156k. This is before one considers the consequences of water and nutrient neutrality restrictions or the housing market downturn. The impact of this is not just felt in those who are deprived of a home, or an alternative to sky high rents and house prices, but to the economy more broadly. At a time when there is a renewed focus from Government on trying to secure growth amidst a relatively stagnant economic landscape, the draft NPPF proposals – if implemented following the consultation – would seem likely to act against that objective.

[1] The Consultation is available here

[2] The Government consultation explains this its analysis is that areas without an up-to-date Local Plan would have 14% higher housing supply if their housing supply (as a proportion of existing housing stock) were as much as those with an up-to-date plan. Unfortunate, this analysis does not address the point that many of the areas without an up-to-date plan are in Green Belt and other restricted areas where the Government’s proposed policy is likely to restrict housing requirements.

[3] The HBF estimates based on a survey of local authorities in the areas affected is that 120,000 homes are currently stalled by restrictions linked to nutrient neutrality, and that this could manifest itself as around 41,000 homes per annum once one takes into account the future flow of allocations and permissions that are affected.

[4] For example, the Oxfordshire Growth Deal was based on a higher target than that set by the Standard Method, but indications are that its constituent members will now revert to a lower number – see here

[5] The London Plan SHMA from 2018 identified need of 66k p.a. The Inspector Panel examining the Plan concluded that adopted target should be 52k p.a. saying, inter alia, that: “the question of supply is based on capacity and given that this would be maximised as far as realistically possible it is difficult to see how the number of deliverable housing units could be increased without consideration being given to a review of the Green Belt or further exploration of potential with local authorities within the wider South East.”

[6] This is the amendment proposed to NPPF para 11 b) ii)

[7] Further, there is no mechanism in place to address the cross b0undary relationship between London and its surrounding local authorities, as demonstrated by the Panel Reports into successive London Plans.

[8] As set out in NPPF proposed changes at para 62 of the consultation draft

[9] As set out in NPPF proposed changes at Para 35 a) which removes that requirement from the “Positively prepared” part of the soundness test that applies to Local Plans. In due course, the LURB proposes to remove the Duty to Cooperate and replace it with a “policy alignment” test

[10] See for example this review of how planners are responding here (£).

[11] There was no obligation to release Green Belt to meet need in full, but many plan makers reviewed the Green Belt and found ‘exceptional circumstances’ for amending its boundaries did exist: see DLUHC Monitoring of Green Belt change here

[12] The provisions on five year housing land supply and their broad consequences are explained here. The provisions on the Housing Delivery Test are explained here

[13] Based on annual PINS data

[14] The research – Mind the Gap – can be found here

[15] See for example, the Land at Castlethorpe Road appeal here

[16] A role defined by the Elphicke-House report (see here) which gave lie to the idea of LPAs as passive players in housing supply

[17] Indeed, in Milton Keynes, the Castlethorpe Road planning inspector concluded that the level of optimism bias would reduce in response to the Government’s then increasing pressure on housing delivery; a more relaxed regime will obviously have the opposite effect.

[18] See the Economic Footprint of House Building in England and Wales here

[19] The Barker Review Final Report – Recommendations is here

[20] Whilst the role of extra supply in improving affordability is disputed in some commentary, there is in fact a widespread consensus (including from the Office for Budget Responsibility) that prices are influenced by supply and that, over time, increased supply acts to moderate house price growth relative to growth in incomes. Professor Glen Bramley of Heriot Watt University found that: “Increased housing supply is part of the solution to the manifest housing problems, not just because of the gradual moderation in price levels it can achieve but also … because it enables much more of other more direct solutions, notably the building of more social and intermediate affordable housing in mixed developments funded by land value capture”. The Redfern Review found: “Long-term increases in supply, sustained over 20+ years will be needed to reduce overall housing market pressure, increasing the ‘size of the cake’ and resulting in a ’positive sum’ gain. Government’s primary role is in guiding the long-term environment that will support its objectives”

[21] See Economist article here (£)

[22] Average House prices for England from ONS House Price Index Q3 2022 to Q3 2023 (£58,000 Median household disposable income (UK) of £32,300 for financial year ending 2022. (after Income Tax, National Insurance and Council Tax).

[23] Unison, 2018. Priced Out: Home ownership and public service workers is here

[24] The Levelling Up White Paper Executive Summary is here

[25] This trend was identified even before the 35% urban uplift was proposed to be enshrined in the NPPF – see Financial Times report here (£)

[26] Centre for London 2022, Making Space available here