The preparation of local plans in England has become a ‘little’ more complicated in recent weeks (if it ever needed more complexity?). A new planning system is on the horizon, following the publication of the planning White Paper ‘Planning for the Future’. Shorter term changes are also proposed to the Standard Method for calculating local housing need, which has received much publicity recently[1] and Lichfields has already crunched the numbers and considered the different figures at a local level. While some of the output figures are on the high side (i.e. Westminster), other figures are surprisingly low (i.e. Liverpool).

For plan-making though, the combination of proposed introduction of a new Standard Method and a wholly new planning system really has thrown the cat amongst the pigeons. Each LPA will need to take stock and work out its next move. Will it be decided to have a ‘White Paper’ Local Plan, to try and rush through a NPPF (2019) Plan or even try to game the system?

This blog maps out the ‘plan-making’ road ahead: considering both the transition to a new planning system in the long term and a new standard method in the short term. Inevitably, this is a complex topic and just the transition itself will be complicated. We look to cut through the complexity here and to consider how LPAs might react in response to their different circumstances. There is some background to the different transitional arrangements, but if you already have some knowledge then you might want to skip ahead:

The Road Ahead: White Paper Plans and the Standard Method 2

A new ‘White Paper’ planning system

We know that a new planning system is coming, underpinned by new legislation. We have looked at the

proposals in-depth here. For this blog, the key thing to know is that the Government wants to give each LPA a binding housing requirement to plan for. This will take into account both housing need in an area (i.e. what the Standard Method currently provides) and relative constraints (or lack of) – i.e. a ‘policy on’ requirement

[2].

Crucially, there is also an expectation that at least some ‘White Paper’ Local Plans will be adopted before the end of this Parliament and the next election in May 2024[3].There are proposed transitional arrangements in terms of moving from the current system to the new ‘White Paper’ planning system

[4]. Under the proposals, each LPA would have a statutory duty to prepare a new ‘White Paper’ Plan:

- 30 months from new legislation coming into force for any LPA without a local plan adopted in the previous three years;

- 42 months from new legislation coming into force for any LPA with a local plan adopted in the previous three years; or

- 42 months from adoption of a current local plan that was submitted for examination prior to the new legislation becoming in force.

Working backwards, the new planning legislation will need to be in force by the end of September 2021 at the very latest, to enable a ‘White Paper’ Local Plan to be adopted before the end of Parliament. This takes account of a 30-month statutory deadline for LPAs without a Local Plan adopted in the previous three years and pre-election Purdah (following the dissolution of Parliament on 28th March 2024).

Standard Method 2

The

proposed changes to the standard method are independent of the White Paper proposals and are described as ‘short term’. Looking back at previous changes to the NPPF (2018), a

consultation commenced at the end of October 2018 and changes were published in mid-February 2019 – c. 4 months. On this basis, we could be looking at ‘Standard Method 2’ being in place before Christmas. However, to simplify our road map, we have assumed that the PPG is updated with the new ‘Standard Method 2’ on

1st January 2021 (a new year’s treat).

Transitional arrangements are proposed in the plan-making context (key to note that similar arrangements are proposed for five-year housing supply) to move us from the current ‘Standard method 1’ to the ‘Standard Method 2’. These are:

- If an LPA has already undertaken a Reg.19 consultation, it has six months from the adoption of ‘Standard Method 2’ to submit its new plan for examination – by our timescales this would be the end of June 2021.

- If an LPA hasn’t undertaken a Reg.19 consultation by the adoption of Standard Method 2, the LPA has three months to do so (i.e. by the end of March 2021) and then has a further six months to submit the plan for examination – i.e. the end of September 2021.

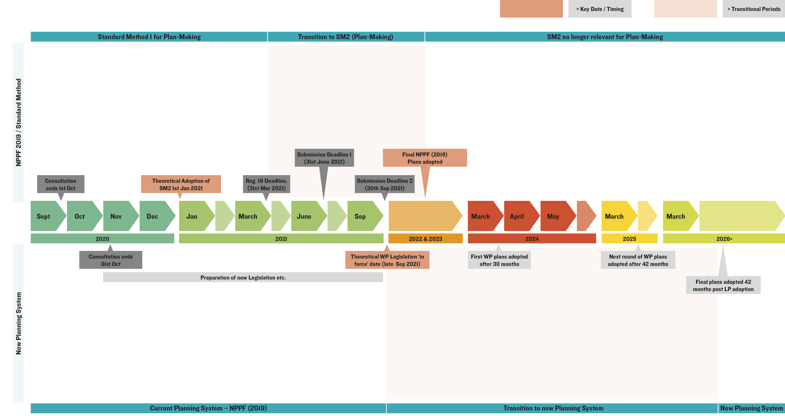

The ‘plan-making’ road map: the transition from the NPPF (2019) to a new planning system

The roadmap identifies a rough timetable for the adoption of ‘Standard Method 2’ and the new White Paper planning system. Obviously, this is based on a number of assumptions, including that the proposed transitional arrangements are implemented as proposed.

How might LPAs react

The circumstances for each LPA will be unique with politics likely to play a large role. However, there are some clear groupings in terms of potential outcomes.

Group 1: Those with a plan adopted within three years of legislation coming in to force

Taking a White Paper legislation ‘in force’ date of September 2021, for LPAs who have adopted a Plan since September 2018 (or will likely go on to adopt a plan from now up until that date) we can assume that its next Local Plan will be in accordance with the new White Paper legislation. Some with Plans on the boundary of September 2018 may be a little nervous as they could just fall through the cracks.

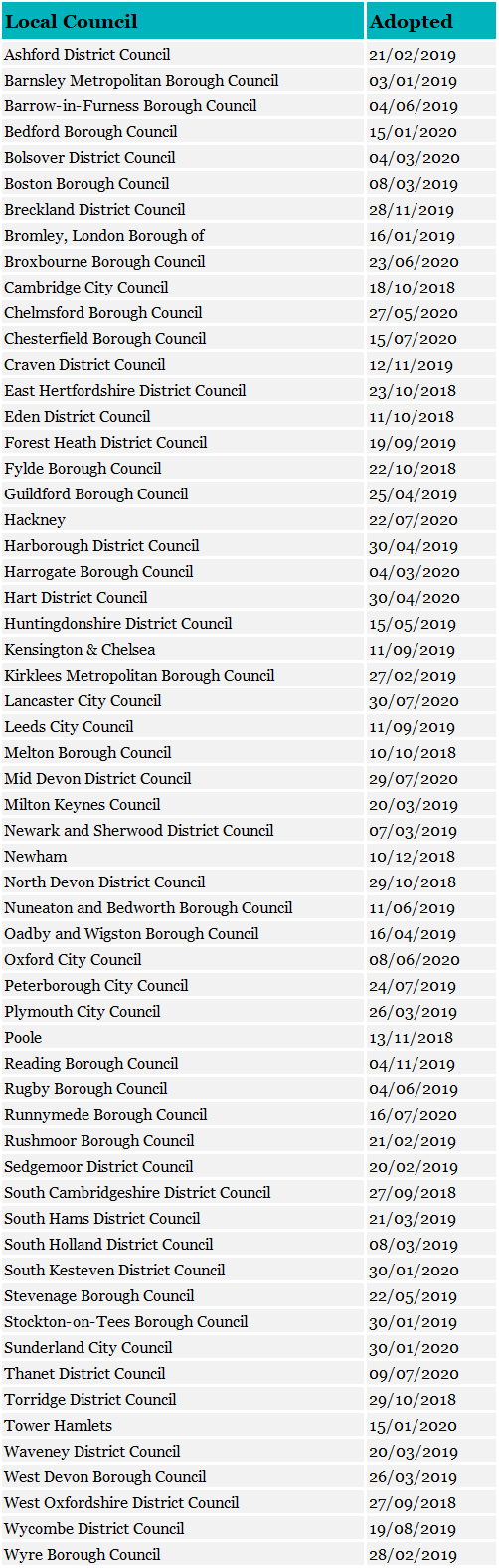

In any case, these authorities will then have 42 months to adopt said ‘White Paper Plan’: c. March/April 2025. Currently, there are only 59 LPAs that fall into this category. A list of these is included at the end of the blog.

Group 2: Those LPAs without a plan adopted within three years of legislation coming into force

The vast majority of LPAs currently fall into this group. The LPAs with Local Plans not already at Examination will be under a pressure to progress with plan-making under the current system and may well already be deep into plan-preparation. These LPAs have an incentive to adopt an NPPF (2019) compliant plan ahead of the new legislation. The incentive being an additional 12 months to prepare and adopt a future ‘White Paper’ Local Plan following the ‘in force’ date.

How each LPA will react in plan-making terms will most likely hinge on its proposed ‘Standard Method 2’ figure:

LPAs with a Standard Method 2 figure above the current standard method

Similar to previous transitional arrangements from the 2012 to the then 2018 NPPF, the new standard method might be the nudge to get on with plan-making for LPAs in this situation. You may recall a flurry of LPAs submitting local plans just before the transitional deadline to the 2018 NPPF. Missing this deadline would have meant that these LPAs Plans would have to be assessed against the then new Standard Method 1 (subject to constraints) instead of their own assessed housing needs.

These LPAs may, therefore, attempt to ramp up plan-making to adhere to transitional arrangements in order to submit a ‘Standard Method 1’ plan; thereby banking a lower housing requirement in the short term and buying more time to make a ‘White Paper’ Local Plan in the longer term. Many LPAs will already have spent many years investing in a new Local Plan with residents and businesses inputting throughout – so it only seems fair that they may take this route. Therefore, expect a flurry of Reg.19 consultations either side of the new year, with Plan Submissions to the Secretary of State following in the summer.

It may take a year or so from Submission of a Local Plan to its adoption: c. Summer 2022. From that point on, each of these LPA would have a further 42 months to prepare a ‘White Paper’ Local Plan – likely to be some time towards the back end of 2025 or 2026. This would give plenty of time to work out how to tackle whatever requirement figure the Government will mandate and gives time for the new system to bed in.

Of course, it is also worth noting that missing the ‘Standard Method 2’ transitional arrangements for these LPAs could have major plan-making implications. There is unlikely to be time to account and plan for a higher Standard Method 2 target, so many of these LPAs may have to wait for the White Paper system to come in to force and prepare a new Plan within the 30-month deadline.

LPAs with a lower Standard Method 2 figure

As a starting point, there will be many – most likely northern – LPAs with, what would appear to be rather low Standard Method 2 figures, when judged against said LPAs ambitions for housing and the ‘Standard Method 1’ outputs. These LPAs may simply ignore the ‘Standard Method 2’ figure even if they miss transitional deadlines and plan for a higher target; akin to the ‘Standard Method 1’ or even go further above that to meet housing/economic ambitions.

A cynic, though, could see a situation arise where an LPA is struggling to meet the Standard Method 1 figure, or is doing so begrudgingly (against local opposition) and, in such cases, these authorities may deliberately wait for the ‘Standard Method 2’ transitional arrangements to pass. That LPA could then subsequently submit a Local Plan for examination – using the ‘Standard Method 2’ as its basis of local housing need – just prior to the White Paper legislation ‘in force’ date. With examination of the Submitted Plan, plus a 42-month timescale to prepare a ‘White Paper’ Local Plan, these LPAs would buy themselves some breathing time to prepare for whatever the Government mandated requirement is further down the line. For these LPAs, they might adopt ‘White Paper’ Plans at the back end of 2025 or early 2026.

And for those LPAs willing to wait it out?

The above has assumed that LPAs will mainly want to have an NPPF (2019) Plan adopted ahead of the new White Paper legislation. This is chiefly to buy themselves time in the transitional measures to adopt a new ‘White Paper’ Local Plan: i.e. having 42-months (the carrot) instead of 30-months (the stick). But what about those who, by design or circumstance, become the early adopters of the new planning system?

For LPAs who are already struggling to plan for the ‘Standard Method 1’ figure, or where they are highly constrained, or where the Standard Method 2’ is also higher - waiting could, arguably, be in their favour. This would depend on the politics of the area, but it’s not hard to imagine an authority with Green Belt/AONB and vocal residents, where holding off plan-making under the current system would be a significantly less controversial option. Given that the White Paper proposes that LPAs will have a housing requirement dictated to them which specifically accounts for constraints, these LPA may decide to hold fire and chance a lower figure later down the line for its ‘White Paper’ Local Plan.

There will also be some LPAs who are in early plan-preparation stage, with less time and money invested, who might just wait. Why spend lots of local authority money on a Plan now, when there will be a statutory duty to prepare one within 30-months - potentially starting from Summer next year?

However, waiting for the new White Paper legislation also brings with it considerable risks and unknowns. A constrained LPAs housing number could well go up, as well as down. There could be delay in the legislation coming forward with legal challenges – leaving LPAs without an up-to-date local plan. This is also a new system after all, that is highly likely to have teething problems.

Finally, there is also the December 2023 deadline for all LPAs to have an ‘up-to-date’ local plan to consider. There was nothing in the White Paper regarding this deadline, nor any recent comments regarding it by Ministers. Assuming it is still in place, waiting to prepare a ‘White Paper’ Plan would mean missing this deadline. We don’t know what measures the Secretary of State would take in these circumstances.

Summary

There are many unknowns and permutations in our roadmap set out above. The introduction of the ‘Standard Method 2’ arguably makes the transition to a new planning system more complicated but may also result in some LPAs working quicker to bring about emerging plans. For those LPAs who end up waiting for the White Paper legislation to make their next Local Plan, there are significant risks and unknowns and so the question is whether local politicians will be willing to take the risk of the unknowns?

The only thing that is clear is that the transition from the current to the new plan-making system will complex. We will need to wait and see what comes out of the consultation process but in the run up to Christmas and over the next few years in general local plan life will be complicated. We will all need to be monitoring local circumstances carefully and consider how these interact with changes to national policy.

Of course, who could be better placed than Lichfields to help in this regard. Follow our blog for upcoming updates on what the various consultations means for local regions across the country. Also, contact one of our local offices if you have a more detailed query.

LPAs with a plan/review/DPD adopted since September 2018. LPAs that have adopted joint plans are individually listed below.

[1] Housebuilding algorithm will lead to more developments in Tory areas, Johnson warned https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/live:bbc_radio_fourfm

[2] Lichfields: Grow, Renew, Protect: The White Paper - ‘Top Down’ Housing Requirements

[3] Paragraph 6.3 of the White Paper[4] As detailed at Paragraphs 2.50 & 2.51 of the White Paper.