Following the recent Tory election victory, where seats were secured in a number of traditional Labour strongholds, the Government's attention appears to have once again turned to the North. As the Country awaits the March 2020 budget announcement, this blog looks at some of the potential benefits of proposed transport infrastructure provision in the north, and the implications for its delivery.

One of the key issues in the North is inadequate transport connectivity which acts as a barrier to attracting investment. This also means that firms cannot tap into the labour market and get the skilled workers they need. A number of infrastructure initiatives are proposed to help address this issue including Northern Powerhouse Rail and HS2 and these initiatives have been carried forward into a range of strategies and transport plans.

For example, the Transport for the North [TfN] Strategic Transport Plan sets a number of objectives to achieve a vison of

“a thriving North of England, where world class transport supports sustainable economic growth, excellent quality of life and improved opportunities for all” [1] including increasing efficiency, reliability, integration, and resilience in the transport system. It seeks to realise the benefits of agglomeration and economic mass, in the North by providing faster, more efficient, reliable and sustainable journeys on the road and rail networks. Under the transformational growth scenario outlined in the plan, it notes that growth is expected in high and medium-skilled occupations (an increase of 35,300 and 1,600 jobs per annum by 2050, respectively).

In addition, the Greater Manchester Strategy, which provides a framework for the Local Industrial Strategy, states that it will capitalise on the investment planned at Manchester Airport, including the arrival of HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail, to strengthen Greater Manchester as an internationally competitive employment location. It emphasises the importance of delivering this infrastructure in order for Greater Manchester to achieve economic growth and states

[2]:

“Given the decision to withdraw from the European Union, we need to focus on maximising our existing competitive advantages. Greater Manchester has always been an outward looking city with a rich history of global trade and welcoming of diversity and talent. Remaining open, international and connected will be ever more important in the coming years. As the heart and driver of the Northern Powerhouse economy, we need to prepare for, and take advantage of, the transformational opportunities major infrastructure improvements, such as HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail, will provide”.

The Strategy notes that a skilled workforce is essential to deliver the key infrastructure projects on which prosperity depends. It emphasises the need to bring together policies and investments around housing and transport to create inclusive, sustainable, growth locations. To provide one example of the amount of employment which may be generated by these strategic infrastructure improvements, GMCA growth and reform plans

[3] suggest that the HS2 hub at Piccadilly station has the potential to create 30,000 additional jobs in the immediate vicinity of the station.

We are also seeing initiatives in the wider North West to help maximise the benefits of new infrastructure provision, such as the Crewe Hub Area Action Plan, which establishes a development framework to facilitate and manage development around a future HS2 station within the town. The proposals include a new commercial district, mixed use commercial and residential development within walking distance of the station, advanced digital infrastructure and vastly improved physical connectivity to the station, supported by environmental and social infrastructure. Development strategies suggest growth at Crewe of around 7,000 new homes and 37,00 new jobs by 2043 as part of this process.

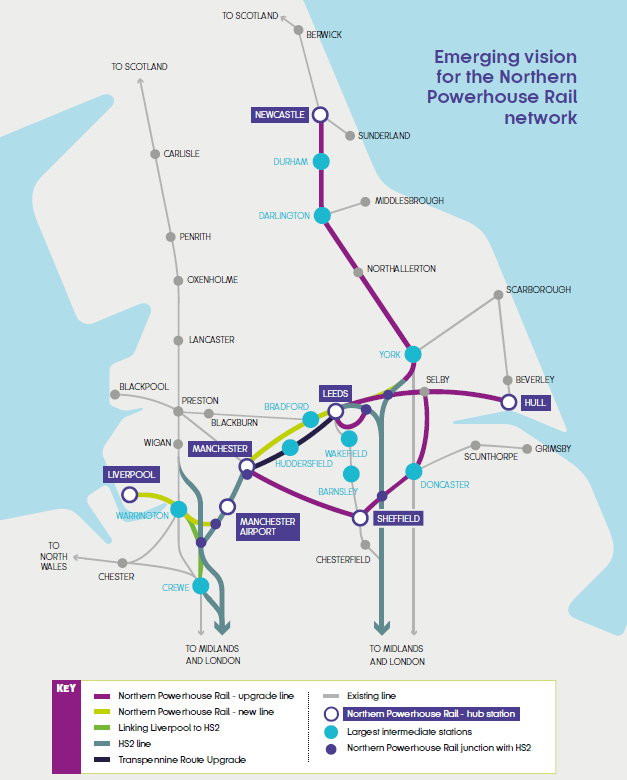

Source: The Potential of Northern Powerhouse Rail – Transport for the North

However, there is a long way to go and those with experience of using the northern rail network will be familiar with delays, slow services, and poor carriage quality which have contributed to the Government’s recent decision to nationalise Northern Rail. This does however help create new possibilities for the future of services in the northern franchise area.

One of the key initiatives for ensuring that sub-regional connectivity is improved is Northern Powerhouse Rail. This would offer much faster, more frequent and reliable rail links and open up new opportunities for people and businesses by linking the North’s six main cities. At the moment, fewer than 2 million people in the North can access four or more of the North’s largest economic centres within an hour. This would rise to 10 million once Northern Powerhouse Rail is delivered; transforming the job market and giving businesses access to skilled workers.

The Prime Minister recently gave his backing for the Leeds to Manchester route which would reduce travel time between the two cities from 50 minutes to less than 30. Major upgrades to four stations, the electrification of lines and the installation of more railway tracks are part of a planned £2.9bn upgrade of the route. Whilst this has been greeted with optimism from some, Liverpool Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram has questioned the focus on Transpennine connectivity over routes linking Liverpool and Manchester.

The delivery of both HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail, in tandem, would arguably do most to achieve economic prosperity and continue to encourage investment in northern businesses. However, it is still not certain whether either scheme will fully deliver.

The cost of HS2 in particular has been subject to criticism from some quarters recently, perhaps most vociferously from Lord Berkeley, the former deputy chair of the Oakervee Review into HS2, who, in his own review of the scheme has claimed the project costs are likely to soar to more than £108 billion. This is almost double from the £56bn expected in 2015. So, it is no surprise to learn that the Transport Secretary, Grant Shapps, requested more data before making a decision on the scheme.

There are currently various levels of commitment to each section of HS2 and the future of the whole network is uncertain. For example, the Rail Reform and High Speed Rail 2 (West Midlands - Crewe) Bill, which gives the powers to build and operate Phase 2a between Birmingham and Crewe, passed through the House of Commons and had completed Second Reading in the House of Lords before the dissolution of the previous Parliament, and was covered in the December 2019 Queen’s Speech. However, reference to Phase 2b, the eastern link of the route, connecting the East Midlands into Yorkshire, was absent in the Queen’s Speech and there have been media reports that Phase 2b could be dropped. A decision on the future of HS2 is expected imminently.

The fate of other schemes has still also yet to be sealed. For example, the proposed £560m ‘Northern Hub’ to increase capacity within a bottleneck at Manchester Piccadilly station, first announced by George Osborne in 2014, has yet to reach fruition.

Over the coming weeks and when the Chancellor’s budget is revealed on 11th March it should hopefully become clearer whether there is a light at the end of the tunnel or whether we will still be stuck at the station.

[1] Transport for the North Strategic Transport Plan, page 6[2] Our People, Our Place: The Greater Manchester Strategy §6.2[3] A Plan for Growth and Reform in Greater Manchester, March 2014