Our

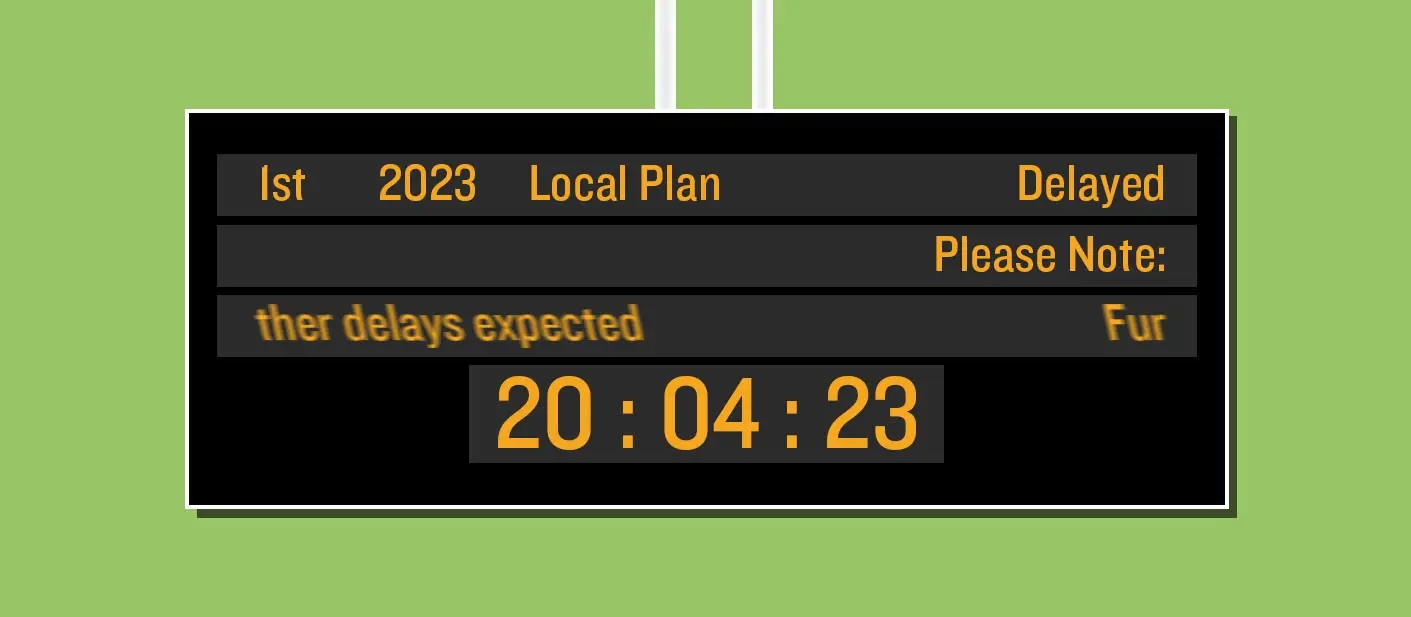

January 2023 blog highlighted the economic and social costs of the 33 Local Plans that had been delayed at that time. Since then, the trend for pausing plan-making has shown no signs of slowing down, with at least 10 further local planning authorities having paused work on their emerging plans since, the majority citing the Government’s proposed planning reforms as the reason for doing so. The potential impacts of the delays in plan-making have also recently been picked up in national media coverage including in The Times

[1] and The Telegraph

[2].

It is important to note that a few local authorities are bucking the trend; in some cases motions to pause plan-making have been defeated. For example, West Berkshire Council recently voted to submit their draft plan to the Planning Inspectorate despite concerns about soundness and the Government’s proposals for planning reform.

Despite some bold outliers pressing on with their plan-making, the overwhelming mood among local planning authorities seems to be a cautious one in terms of proceeding with their emerging plans, and we expect that more authorities will be pressing pause in the coming weeks and months. In some cases where plans are at examination, Inspectors themselves have suggested that authorities pause their work to consider the outcome of the Government’s consultation – for example Solihull and Mole Valley. As we highlighted in our previous blog, there are significant implications for society when LPAs put plan-making on hold, including:

Homes Foregone – we have estimated that we are forgoing c.11,200 homes per year in the absence of ambitious local plan-making (and this is likely to be a conservative estimate);

Economic Costs – the homes foregone figure translates into an estimated combined construction value of £11.09bn, which would support 8,700 direct jobs and 10,700 indirect jobs – and result in £145m of Council Tax per annum when the developments were completed (at today’s rates);

Other Societal Costs – new development, when properly planned for through local plan allocations, provides a whole host of benefits to society including new schools, health centres, green spaces and sports provision. In the absence of new housing, these benefits are not being delivered.

Looking ahead

Amid continuing uncertainty regarding the Government’s proposals for planning reform, this leads us to ask how many more local planning authorities might pause work on their local plans. As a starting point, we have referred to the list maintained by the Planning Inspectorate

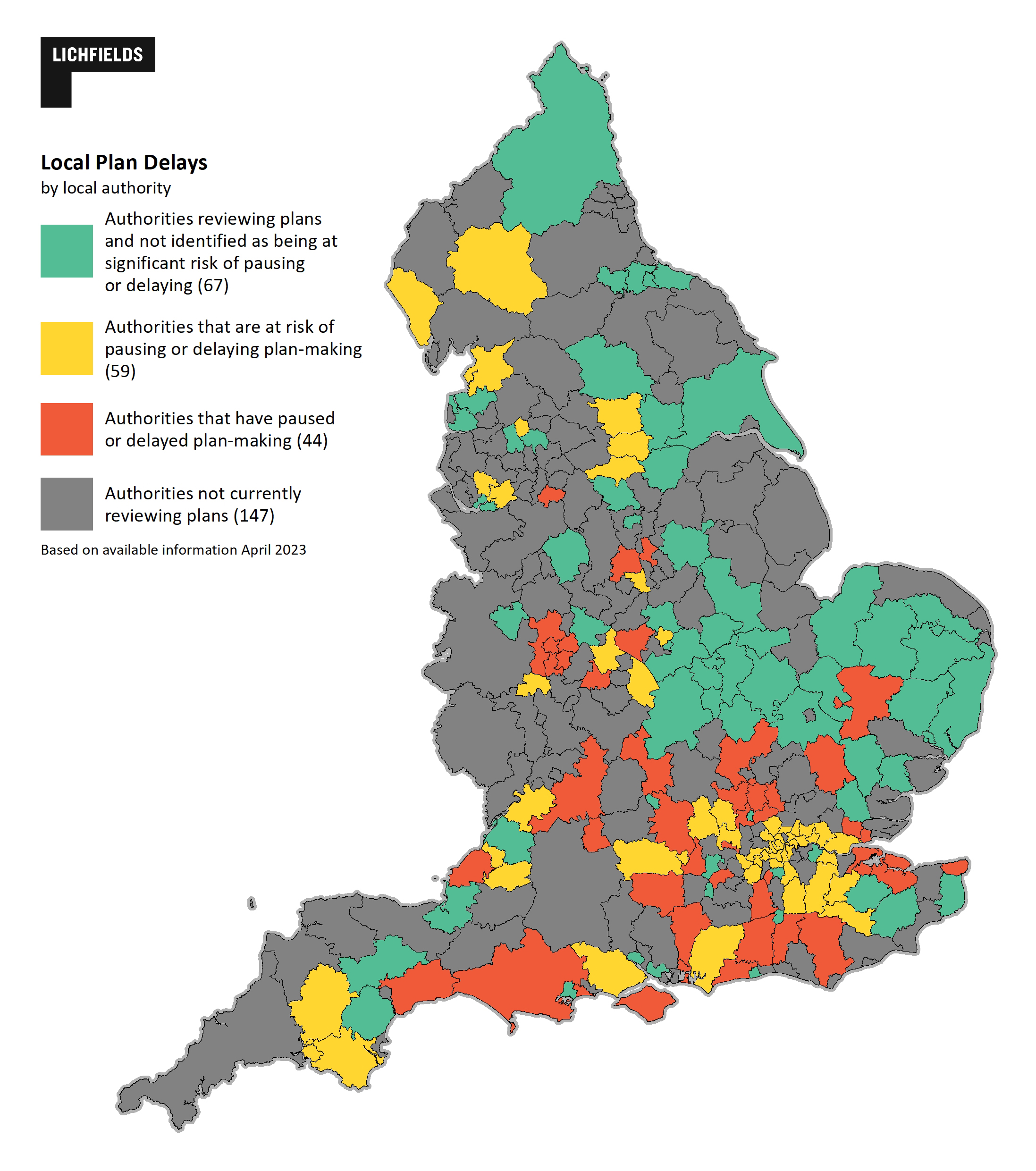

[3] to establish how many authorities are currently undergoing reviews; as of the latest update on 20 March 2023, 170 authorities are undertaking a review of their Local Plan, although 44 have already paused work.

We have then considered which authorities might be at risk of pausing plan-making; logically this would be those whose housing target might reduce as a result of the amendments to the NPPF. This includes:

London authorities – London currently delivers far less housing than its requirement as calculated by the standard method. Looking forward, NPPF proposals that relate to character could put the brakes on higher density developments, particularly in outer London Boroughs.

Other authorities subject to the 35% uplift – there are 19 other large cities which are subject to a 35% uplift to their Local Housing Need. With reduced scope to densify ‘out of character’ (as in London), no need to review Green Belt, and a weakened expectation for neighbouring authorities to address any unmet need, the impact of the NPPF proposals is that the housing requirement in these areas is likely to be reduced in the future.

Green Belt authorities – under the Government’s proposed NPPF reforms, there will be no requirement to review the Green Belt when preparing new local plans to meet housing need. There will also be less scope to build at high densities and weakened expectation for cross-boundary re-distribution. Consequently, authorities that are significantly constrained by Green Belt (over 50%) are therefore likely to be able to target lower levels of housing delivery.

Other NPPF ‘Footnote 7’ authorities[4] – with increased emphasis on protecting ‘character’ in the proposed NPPF amendments, authorities that are significantly constrained by ‘Footnote 7’ designations (i.e. where such constraints cover more than 50% of total area) are likely to have increased justification for strongly protecting these areas from development through reduced housing requirements.

In the short term, the potential opportunity to reduce local plan housing requirements may well prompt a delay to work on emerging local plans. Of the 126 authorities that currently still working on a review of their local plans:

- 22 are London Boroughs;

- A further five authorities are subject to the 35% uplift;

- A further 20 authorities are subject to significant Green Belt constraints (more than 50% of total area); and,

- A further 12 are subject to other ‘Footnote 7’ constraints (more than 50% of total area).

Therefore, in addition to the 44 authorities that have already paused work on their local plan review we estimate that a further 59 authorities are at risk of following suit. This would equate to a total of 103 of 170 authorities that have commenced a local plan review either pausing or being at risk of doing so as a result of the Government’s proposed planning reforms. This is a matter of very significant concern and should be viewed in the context of the Government’s recent consultation on reforms to national planning policy stating that “

Our proposed changes for planning for housing are intended to support plan-making and in doing so help deliver more homes.”

[5]Ironically, the consultation itself, and the lack of certainty over the future of planning reform, has led to an impasse in plan-making across the country which will result in thousands of new homes along with the associated benefits and infrastructure being held up. By our estimates, almost two-thirds of the authorities currently reviewing their Local Plans are putting this process on hold or are at risk of doing so.

[1] UK housing crisis: planning targets scrapped in ‘win for nimbys’, The Times

[2] Councils scrapping building targets will make housing crisis 'even worse', The Telegraph

[3] Local Plan: monitoring progress, Gov.uk

[4] Footnote 7 of the NPPF includes other designations which can provide a strong reason for restricting development, including Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, National Park designations, designated heritage assets, and areas at risk of flooding or coastal change.

[5] Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill: reforms to national planning policy, Gov.uk (paragraph 6).