[1] Shakespeare, T – writing within Davis, LJ (2013), ‘The Disability Studies Reader’, Routledge, 214-221.

Our award winning blog gives a fresh perspective on the latest trends in planning and development.

[1] Shakespeare, T – writing within Davis, LJ (2013), ‘The Disability Studies Reader’, Routledge, 214-221.

Lichfields is currently monitoring the draft London Plan Examination in Public (EiP), which is scheduled to last until May 2019, and will report on relevant updates as part of a blog series. The sixth blog of the series focuses on the hearing sessions for draft policies D1-D3 and the Plan’s approach to delivering good and inclusive design, which took place on 5 March 2019.

Well intentioned, though too detailed

Are the policies genuinely inclusive?

On inclusive design, a number of participants felt the way this was conceptualised in the draft Plan focused too heavily on physical impairments and disabilities. For example, a representative for the NHS Clinical Commissioning Group argued that far greater consideration should be given to how cognitive and sensory impairments are accounted for. Inconsistencies were also raised as to how inclusiveness is defined in policy D3 and within the glossary. The GLA took these comments on board and confirmed they would review these points.

Others called for greater consideration of economic exclusion, alongside access to local services and amenities; it was also considered whether the social heritage of place should be given greater status; and more generally, whether the policies focused too heavily on the physical dimensions of urban design.

There was some discussion on the use of planning conditions to ensure public access to the private realm, though the GLA felt that many of these other points were addressed in other sections of the Plan. The GLA also stated that whilst the draft Plan’s design policies did focus on the physical aspects of the built environment, these qualities have a very real impact on people’s individual experiences of the city, affecting our mobility, perceptions of safety and personal comfort and well-being.

Scrutinising design scrutiny

In terms of scrutiny, concerns were raised over design review policies at D2 F and G. Many felt the policies focused too heavily on schemes referable to the Mayor, whilst the thresholds associated with such schemes were thought as being relatively arbitrary from a design perspective.

A representative for the City of London Corporation stated that most new developments in the City are taller than the 30m threshold, as a result they have extensive in-house experience and resources. It was felt onerous to require additional review from external independent experts, especially given that they already consult widely with other design and heritage bodies when scrutinising taller schemes. However, this point was addressed by the GLA in its written statement (and subsequent minor suggested amendment to Policy D2 F), which clarified that ‘design review does not need to be undertaken by external panels; if boroughs follow the processes set out in the Policies, this can be done in-house’.

Countering this, the Design Council felt that many schemes below the threshold would benefit from design review; although the reviews focused too heavily on individual buildings in isolation, with not enough attention paid to the cumulative impact that multiple new developments can have on an area.

Beyond this, it was noted that the policies should be more explicit as to when a local authority should request development proposals to undergo an independent review. Also, wider concerns raised over the lack of consistency, as well as the quality of feedback and advice given at design review, with calls for greater standardisation across the board.

A need for more (local) design guidance

Extract from the Mayor of London’s Design Review Survey reveals the small proportion of planning applications that undergo design review

Problems of resourcing and skills

Whilst Policy D2 D does encourage the creation of supplementary design tools, overall, many felt that local authorities did not have the sufficient in-house expertise or skills to produce these. Also, local character appraisals, guidance and design codes would take significant resourcing and funds to undertake, whilst there would be a significant lag before these policies had any effect.

The GLA were sympathetic to resourcing constraints, though drew attention to the efforts being made by some London authorities. It was agreed that there was a need for existing planners to be upskilled, whilst more design specialists needed to be recruited.

The GLA noted that it was raising the profile and importance of design in local authorities via schemes like Public Practice which it is currently expanding, and that the Homebuilding Capacity Fund would also help build the skills at local authority level.

The Mayor’s Good Growth by Design programme hopes to address the challenges facing London’s built environment, by helping to ensure appropriate standards are in place, building capacity, supporting diversity, and championing good design

Next steps

Overall, it seems the Mayor and his team will have a lot to consider moving forward. Like many other sections of the Plan, the design policies would likely benefit from being cut back, referring more explicitly to guidance, and concentrating specifically on matters of strategic importance.

Ensuring that new development meets high design standards will largely be down to London Boroughs. As stated, this will be dependent on the willingness of local authorities, whether there are robust local policies and planning tools in place, and having the staff with the necessary design skills in place, to produce guidance and make sound planning decisions. With much of this dependent on resourcing and funding, the Mayor will be somewhat constrained by funding agreements with central Government.

The issues discussed at the session must also be understood in the context of the wider suite of policies included in the draft Plan’s design chapter, which cover a range of inter-related issues, including density, tall buildings, the public realm. These will arguably have as much, if not greater, impact on how London looks and feels in the future.

Whilst a final version of the London Plan still seems a long way off, it was reassuring to see high levels of engagement on the subject of design, and a genuine willingness from all to strive for higher standards of placemaking across London.

[i] Mayor of London, draft new London Plan: Chapter 3 - Design, Policy D1-D3

[ii] 'Public Space Public Life' study in London 2004, conducted by Gehl Architects for 'Central London Partnership' and 'Transport for London'

[iii] Mayor of London, Planning Capacity Survey

This blog has been written in general terms and cannot be relied on to cover specific situations. We recommend that you obtain professional advice before acting or refrain from acting on any of the contents of this blog. Lichfields accepts no duty of care or liability for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting as a result of any material in this blog. © Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 2019, trading as Lichfields. All Rights Reserved. Registered in England, no 2778116. 14 Regent’s Wharf, All Saints Street, London N1 9RL. Designed by Lichfields 2019.

Image credit: Paul Hudson

Lichfields is currently monitoring the draft London Plan Examination in Public (EiP), which is scheduled to last until May 2019, and will report on relevant updates as part of a blog series. The fifth blog of the series focuses on the hearing sessions for draft policies E4 – E7 on land for industry, logistics and services, which took place on 19 March 2019.

The overriding consensus during the hearing session was one of support for the principle of the Mayor’s proposed policies and, in particular, the rationale for protecting precious remaining industrial capacity in the Capital. On detailed matters however, there was a great deal of disagreement and debate over key assumptions that feature in the policies E4-E7, with many participants questioning the ability of the proposed policies to effectively deliver the Mayor’s objective.

In essence, the majority of discussion coalesced around the following key issues and concerns:

1. What are we actually planning for?

The draft London Plan does not present a specific requirement for industrial floorspace over the life of the Plan, nor set a target for industrial land provision. The GLA says this is intentional, as it does not wish to be “too prescriptive”; however, without an identified requirement, it remains difficult to decipher the overall quantum and scale of industrial space that is being planned for across the Capital – and within individual Boroughs – over the next 25 years. It also makes it tricky to establish a clear logic chain to arrive at the Mayor’s updated Borough-level categorisations for managing industrial capacity (see Figure 1 below). Much confusion was expressed over what the ‘provide capacity’, ‘retain capacity’ and ‘limited release’ categories actually mean in practice, and how they should be translated down into Borough-level development plans.

Figure 1: Managing industrial floorspace capacity – draft London Plan categorisations

Source: Lichfields analysis, drawing on draft London Plan (December 2017)

For instance, as a ‘provide capacity’ borough, Enfield is looking to its green belt for a possible release valve, albeit this is heavily protected by other plan policies (such as proposed policy G2). With industrial intensification failing to date but required by policy, they have had to accept the strong likelihood of under-delivering.

Complicating matters further is a complex supply-side situation, with an apparent lack of clarity over the scale and spatial distribution of ‘pipeline’ industrial land that has already been earmarked for release (for instance through Housing Zones and Opportunity Areas). The GLA acknowledged that a shortfall is highly likely (when demand is compared with supply) but appeared to struggle to quantify or clarify what this shortfall could look like.

2. Intensifying industrial space – is it commercially viable?

The hearing discussions moved onto the principle of intensification (i.e. achieving more intensive and efficient use of industrial land). This is identified by the draft London Plan (and re-iterated by GLA representatives during the session) as the only realistic mechanism or source of supply for accommodating future industrial needs within the Capital, in the absence of ‘new land’ being made available. The draft policies introduce a 65% plot ratio (i.e. ratio of floorspace to land) as a benchmark against which the principle of ‘no net loss’ will be measured. For designated sites to be redeveloped, there would be an expectation that existing on-site floorspace is replaced in full or at a 65% plot ratio – whichever is greater.

The intention may be to prevent developers from ‘gaining the system’, but representors unanimously argued that a 65% blanket ratio is too high, not commercially viable (at single storey level at least) and would act as a significant disincentive to occupiers redeveloping their space for whom a lower plot ratio is operationally critical. Various evidence was cited (including by logistics developer Segro) to suggest that current industrial plot ratios in London typically average more like 45% at best. Lichfields’ own analysis indicates that the current average plot ratio on designated industrial sites in Outer London is currently just 33%, with no sign that intensification is happening at any significant scale, based on industrial floorspace growth trends in Outer London during the past 15 years. Intensification, it was argued, should be recognised as a potentially useful ‘windfall’ source of capacity, but not the primary strategy for meeting future needs.

In response to these concerns, the Mayor has proposed a suggested change to Policy E4 to reflect the fact that some industrial uses require significant yard and servicing space, so that “in some instances, this may provide exceptional justification for a plot ratio that is lower than 65 per cent on development for industrial uses only”. A welcome flexibility, albeit the GLA is keen to retain its statement of intent.

Participants also pointed out the potential planning issues that could pose unintended consequences from industrial intensification, including pressure on roads/highways capacity and parking, unless the necessary infrastructure upgrades are implemented in parallel.

3. Non-designated sites – time to protect?

Alongside a more concerted effort to encourage more efficient use of existing sites, the draft London Plan’s shift in policy approach may also require London boroughs to re-visit and re-consider how much formal protection should be given to currently un-designated industrial sites. These make up more than a third of London’s industrial land (36%) and remain particularly susceptible to future release. Our recent analysis suggests that pressures are likely to be most acute in Central Services Circle Boroughs where the current level of protection is weakest (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Non-designated industrial land supply as a proportion of total by borough (2015)

Source: Lichfields analysis, drawing on GLA London Industrial Land Supply & Economy Study 2015 (March 2016)

4. How will the bolder approach be monitored and enforced?

Purpose and intended audience

The updated guidance is less specific than the 1996 guidance in terms of what repairs and alterations are likely to be acceptable in practice. As with the move from PPG15 to the NPPF in 2012, the new guidance adopts a principles-based approach where its predecessor dealt with specifics. This is fine for the professional, but one wonders whether homeowners may be disappointed not to find more specific advice, particularly if they are looking to carry out sensitive repairs or alterations themselves.

Time period: 1715-1900

The guidance notes that the period of houses at which the guidance is aimed is 1715 – c.1900. We welcome the inclusion of terraced houses from 1860-1900 in this guidance, as there are many examples of late Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses which are under-appreciated due to claims that their standardisation renders them of lesser architectural and historic interest.

The First World War formed a watershed, after which there was a move to lower density suburban housing in the form of Homes for Heroes and the garden city movement. These were seen as measures for achieving healthy living, in accordance with early town planning principles which expounded the benefits of lower densities.

Perhaps a bracket of up to c.1914 would appear to be a more logical approach for the guidance on terraced housing, as some towns outside of London—particularly those with high population pressures such as Plymouth and Portsmouth—continued to build terraced houses designed by local architects during the Edwardian period (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The terraced houses along Burleigh Park Road in Plymouth were designed by Daniel Ward in 1906

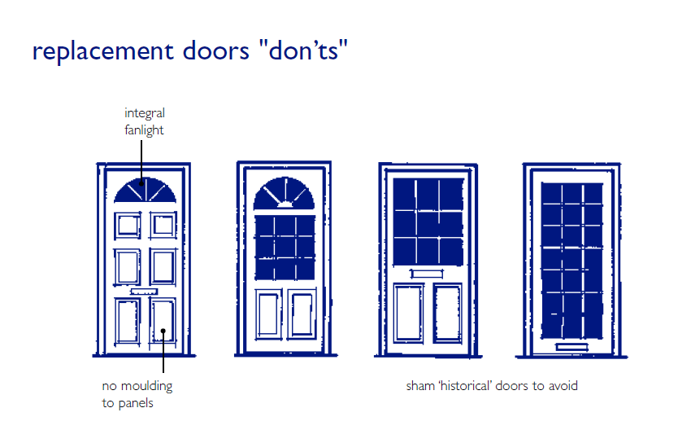

Figure 2: Example extract from Preston City Council's Supplementary Planning Guidance 5 Design Guide on the Repair and Replacement of Traditional Doors and Windows (removed from circulation), which usefully provided examples of inappropriate faux-historical door styles to avoid

Legislation/policy compliance

It’s noted in the introduction that this guide will be of most use to those dealing with requests for listed building consent, though the document will also be of use for other historic terraces which aren’t listed but may be included in conservation areas.

It omits note of the general lack of designation for late-Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses. These houses fall outside the 1850 date beyond which the DCMS ‘Principles of Selection’ (November 2018) notes that ‘greater selection’ for listing is required. Given the limited extent of listed building designation for terraced housing, it might be helpful to include a brief policy compliance section, outlining what is permissible for listed terraced houses; those in conservation areas; and those which are locally listed or non-designated. It may also be useful to note that some terraced houses are subject to restrictive covenants which control changes to their appearance or built form, for example in Tothill Avenue in Plymouth (see Figure 3).

Helpfully, the document highlights the Party Wall Act for Houses of Multiple Occupation, which must be complied with. It also encourages engagement with the local authority in accordance with best practice.

Figure 3: Tothill Avenue’s terraced houses are not listed, in a conservation area or locally listed, though they are subject to restrictive covenants which required the continuity with adjacent terraces to be maintained and required that no changes be made to the boundary walls, railings and fences