On the day of publication of Sir Oliver Letwin’s final review report, we release some initial findings from Lichfields’ own new research on the build out rates on large housing sites. This updates our award-winning research report – Start to Finish – from November 2016, which won the RTPI Research Award in 2017, and which is a regular point of reference for plan-makers and Inspectors in considering the realism of housing trajectories in local plans and five-year housing land supply statements.

Planning for housing involves more than just allocating sites in local plans and granting planning permission for development to take place, although the latter is obviously a pre-requisite. With the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) requirement for local plans to identify sites and broad locations over a 15-year timeframe, for local authorities to demonstrate five-year housing land supply, and also be confident that they will pass the housing delivery test, planners nowadays require a much sharper focus on what sites will contribute in practice, and thinking about how they can – in the words of Kit Malthouse MP – do more, better, faster.

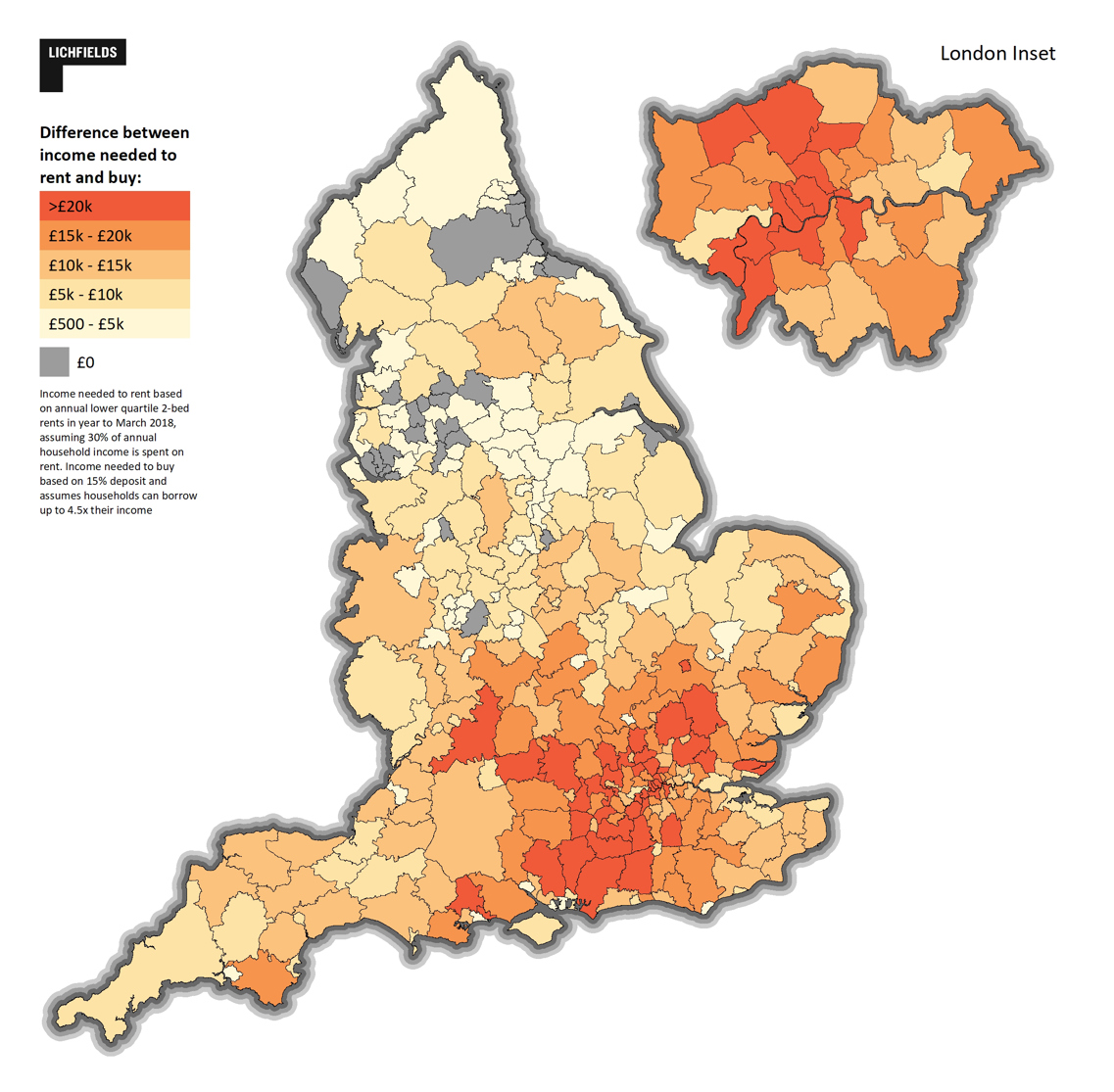

Sir Oliver Letwin’s review focusses on examining why it is that some large-scale housing sites are not delivering homes fast enough and what can be done to increase the speed of build out. His draft analysis was based on a relatively small number of sites (17, of which 15 had data) primarily in the south of England. This reflects the difficulties gathering good quality information on the build out of sites, and explains why many local plans have consistently over-estimated the speed at which developments come forward and then build out. This reflects that many such developments are inevitably complex to bring forward, with significant upfront infrastructure obligations in many cases.

Nevertheless, paragraph 72 of the revised NPPF makes clear the Government view that:

“The supply of large numbers of new homes can often be best achieved through planning for larger scale development, such as new settlements or significant extensions to existing villages and towns, provided they are well located and designed, and supported by the necessary infrastructure and facilities. Working with the support of their communities, and with other authorities if appropriate, strategic policy-making authorities should identify suitable locations for such development where this can help to meet identified needs in a sustainable way.”

It goes on to require that in identifying locations, plan makers should:

“[…] d) make a realistic assessment of likely rates of delivery, given the lead-in times for large scale sites, and identify opportunities for supporting rapid implementation (such as through joint ventures or locally-led development corporations).”

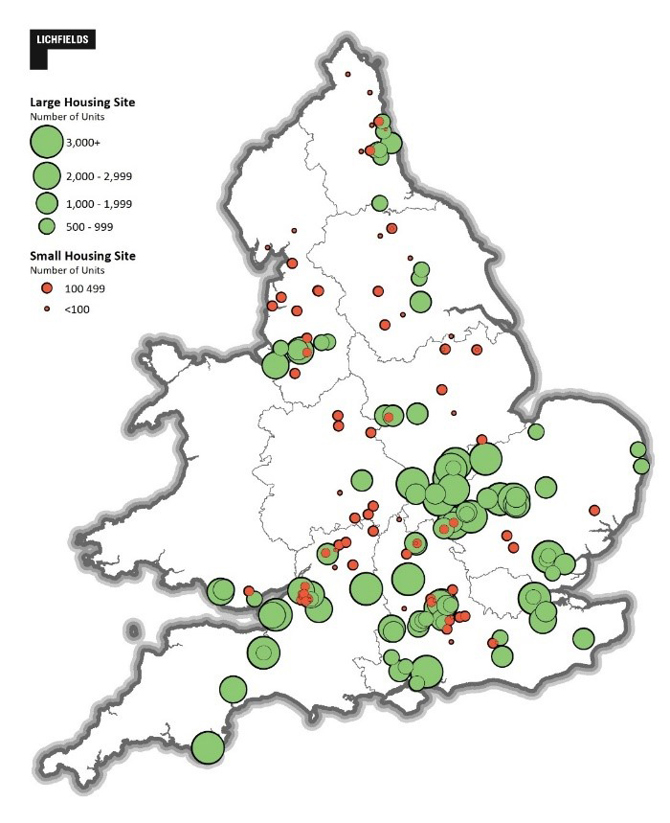

To help inform that analysis, Lichfields has assembled an updated evidence base on lead-in times and build out rates, based on the identification of additional sites, and with two additional years of build out analysis (2016 to 2018).

Our updated analysis considers close to 200 housing sites, including approximately 100 large-scale housing sites and a similar number of smaller housing sites for comparison. These were spread across England and Wales, and ranged from 10 to 15,000 homes. Our analysis considered a wide range of factors which might affect build out rates, including levels of demand, the number of sales outlets, and delivery cycles.

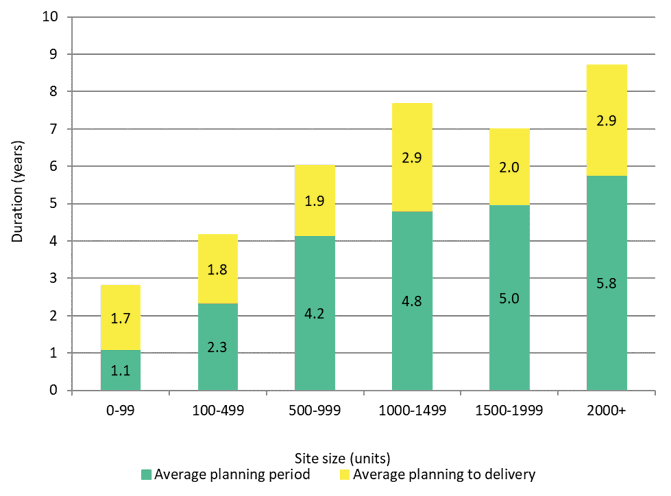

Our analysis measures the “planning approval period” from the validation date of the first planning application on the site, to the decision date of the first application for dwellings in the scheme (whether full, hybrid or reserved matters); as well as the “planning to delivery” period, that is, the period from the approval of the first application for the development of dwellings and the completion of the first dwelling.

The analysis highlights how a site size of 500 units seems to be the tipping point for much longer planning periods (going from 2.3 years to 4+ years, and 5-6 years for sites over 1,000 units). Whilst the planning to delivery period (from planning permission to first completion) is longer for larger sites (on average), this is perhaps less significant a difference than one might expect given the complexities involved.

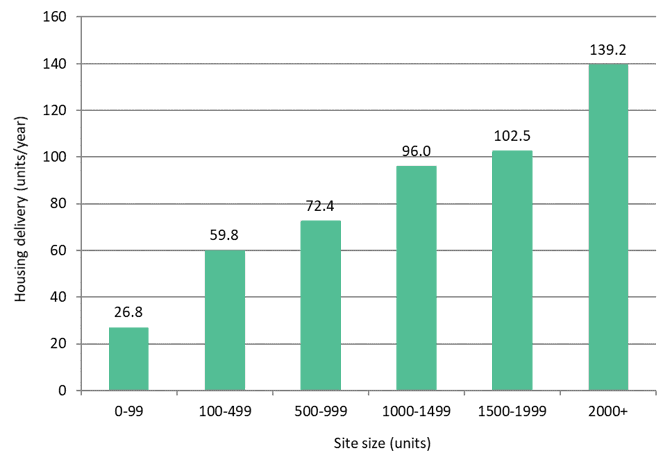

Our research looks at how fast such sites build out once started. The analysis shows the size of a site is one of the key metrics which determines its build out rate. Whilst some very large sites can deliver upwards of 250-300 dwellings per annum for short periods, many sites do not delivery particularly quickly, with the average for sites of 1,000-1,999 homes being around 100 per annum. Nevertheless, sites for over 2,000 homes in our sample delivered on average about twice as many per year than sites of 500-999 dwellings.

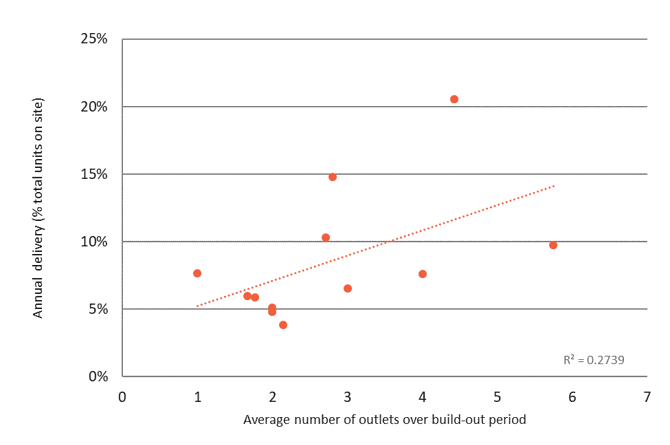

Our research finds that the average number of outlets on a site over the entire build out period has a relatively strong correlation with average annual build out rates as a percentage of total units on site, suggesting that more ‘flags’ and product have a positive impact on the delivery of new housing – a key initial finding of Letwin’s Draft Analysis too. Our sample of sites with outlet data finds that each additional outlet resulted in an average of approximately four homes being completed per month, although a review of annual reporting for major housebuilders suggests the average is closer to three homes per outlet per month (and that there is surprisingly little variation, albeit that they are national averages and may be counted differently be different housebuilders).

Reflecting our original analysis, we also found that very high levels of affordable housing (making up more than 40% of the total units on site) could have a similarly positive impact on build out rates to additional outlets.

We also estimate that greenfield sites may build out up to 21% quicker in delivering, for their size, although on average these take 7% longer from first application until the time they deliver.

Our findings point to the ongoing need for realism and depth in understanding the rate at which large-scale housing sites build out, and also that the most significant element of the time it takes for such sites to move from conception to delivery remains the time it takes to be granted a full, implementable planning permission. There are clear factors that determine the different rates at which sites build out – notably the differentiation in product, the number of outlets and so on – and the extent to which there are policy levers to pull in speeding up build out once sites have started has been a focus of the Letwin Review.

Whilst public sector market interventions – e.g. by Homes England in unlocking sites, or pump priming new infrastructure such as access roads to open up new ‘frontages’ – are already part of the solution, there are limits to the capacity for this type of intervention, and the vast majority of large sites will be privately-delivered. In this regard, interventions will inevitably be via the planning system and how infrastructure is at the very least part-funded via planning obligations and community infrastructure levy for delivering homes. Here, there are risks of unintended consequences of possible planning policy changes that could stall large-scale site promotion, thereby stymieing the necessary investment in up-front infrastructure.

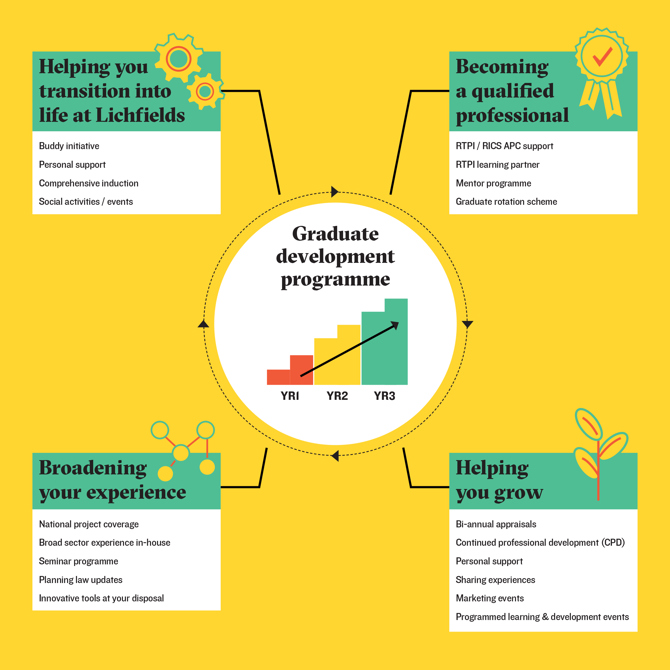

If you would like to speak to someone at Lichfields to find out more about our latest research on build out and land supply calculations, please contact Matthew Spry or Rachel Clements.