What will be the effect of the WMS changes to the 2021 HDT?

Is there a rationale for a 5-month discount due to Covid?

- As a starting point, the lockdown was formally made on the 23rd March and Government lifted restrictions on people who could not work from home on the 10th May (less than two months of full closures). Based on trading updates, most housebuilders were reporting they were back up to a good level of capacity by May-July last year. (e.g. Berkeley noted that production capacity had fallen to 40% but had by June increased to 80%[3], Bellway in June 2020 noted they were back constructing 230 of their sites[4]; and Barratt stated in July 2020 they were at c.75% of pre-covid levels[5]);

- In the final quarter of 2020/21 (Q1 2021) there were the highest number of new build completions in over 20-years, 4% above the same period in the 2019/20 year, with new build housing completions just c.10% lower in 2020/21 than the previous year[6];

- Housebuilder releases show a return to pre-pandemic levels. By way of example Barratt in FY20 (covering the year to 30 June 2020 and most of the pandemic impacted period) completed 12,604 homes, compared to 17,865 in FY19 and 17,243 in FY21, indicating the whole the pandemic created a c.29% effect on business (c.3.5 months of output)[7]; and

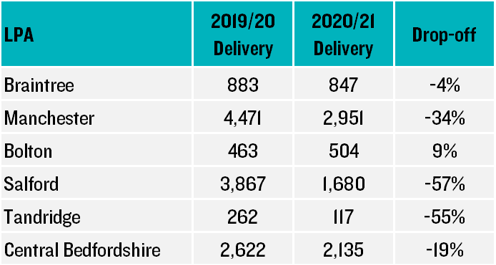

- Looking at a few LPA examples (see table) where monitoring figures are already released for 2020/21 completions figures have ranged from +9% to -57% on the previous year, with an average drop-off of around a third. Of course, these six LPAs may not be representative for all of England but might support the four month discount for 2020/21 as being in the right ball park.

What next: The ‘hawk’ vs ‘dove’

[1] This might be viewed as generous given the initial lockdown was enforced from 23rd of that month. [2] The WMS can be found here[3] https://www.berkeleygroup.co.uk/media/pdf/q/f/FY20_Results_Announcement_June_2020.pdf[4] https://www.bellwayplc.co.uk/media/1738/2020-04-30-covid-19-update-final.pdf[5] https://www.barrattdevelopments.co.uk/media/media-releases/pr-2020/pr-06-07-20[6] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/home-building-stats-show-continued-increase-in-starts-and-completions-despite-pandemic[7] https://www.barrattdevelopments.co.uk/media/media-releases/pr-2021/pr-14-07-2021[8] Although our research report on the HDT – Effective or Defective – found that in four out of five cases, the authorities that fail the most punitive threshold (application of para 11(d)) are those that cannot demonstrate an up to date Five Year Housing Land Supply, meaning the tilted balance has already been triggered via another avenue. In addition, around half of the authorities that fail this threshold are significantly constrained by Green Belt and/or other NPPF Footnote 7 designations, meaning that the ‘very special circumstances’ (or similar) required to justify new housing development will, in many cases, over-ride the tilted balance.[9] As reported here