Sadiq Khan’s London Plan has now been formally published, more than three years on from the publication of its first draft.

As many readers will be aware, the London Plan forms part of the development plan for all London boroughs, as such planning applications in London will be considered against the new London Plan’s policies and those within the individual borough local plans – albeit the Mayor of London has been giving increasing weight to the policies of the new Plan for some time.

This final version of the Plan has been publicly available since 21 December 2020, following the Mayor issuing his Publication version of the Plan for final approval, after having incorporated the majority of the directed changes from the Secretary of State (SoS) earlier on in that month. This January the SoS wrote to the Mayor, confirming that he would not direct any further changes to the Plan, allowing the Mayor to proceed, notably just in time for the pre-election restrictions that might have complicated its publication.

Alongside the Plan, the Mayor has provided a

Saving Statement in relation to existing Supplementary Planning Guidance for the 2016 London Plan, setting out where text within existing SPGs will be retained. This confirms that there will be inconsistencies between the saved SPG and the 2021 London Plan, “Where these arise, the 2020 [sic] London Plan takes precedence as the most up to date document and as part of the statutory development plan.” A set of

presentation slides have also been included, these provide an overview of the Plan's vision and how its policies seek to respond to a number of current issues, including the housing crisis, climate emergency, and London's response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Mayor’s approved Plan is markedly different to that which was originally proposed back in 2017. Following its Examination in Public, the Plan’s overall Housing Target had already reduced by 19.5%, following the tempering of the Mayor’s small sites policy. The SoS’s further directions have arguably resulted in even more significant change, with the Mayor having changed tack on a number of core policies, including Green Belt, Strategic Industrial Land, tall buildings and density, as well as car parking.

To provide an overview of how this might shape future development in the capital, we have summarised how these final amendments might alter future patterns of development across the capital.

1. Green Belt and Metropolitan Open Land

The published Plan incorporates the changes directed by the SoS to the Plan’s Green Belt Policy G2, in order to bring this in line with national policy, removing the blanket ban on development on London’s Green Belt and Metropolitan Open Land (MOL).

Green Belt Policy is now more closely aligned with paras 84 and 85 of the NPPF (the 2012 version, which the Plan has been assessed against), which require development proposals that would harm the Green Belt to be refused except where very special circumstances can be demonstrated. The Plan now also encourages opportunities for the enhancement of the Green Belt where this can provide appropriate multifunctional beneficial uses for Londoners.

Policy G3 regarding MOL has also been diluted, with a similar redaction of the previous text that explicitly stated that development proposals that would harm MOL should be refused.

Changes to this particularly contentious area of planning policy will likely draw a mix of reactions. Not only has this required the Mayor to dilute his 2016 manifesto pledge to protect London’s Green Belt and MOL; some outer London Boroughs may now find themselves under pressure to release Green Belt in order to meet the new housing targets, in situations where closer scrutiny of housing land supply reveals they do not have sufficient deliverable and developable capacity without doing so (a topic explored in our recent Insight report:

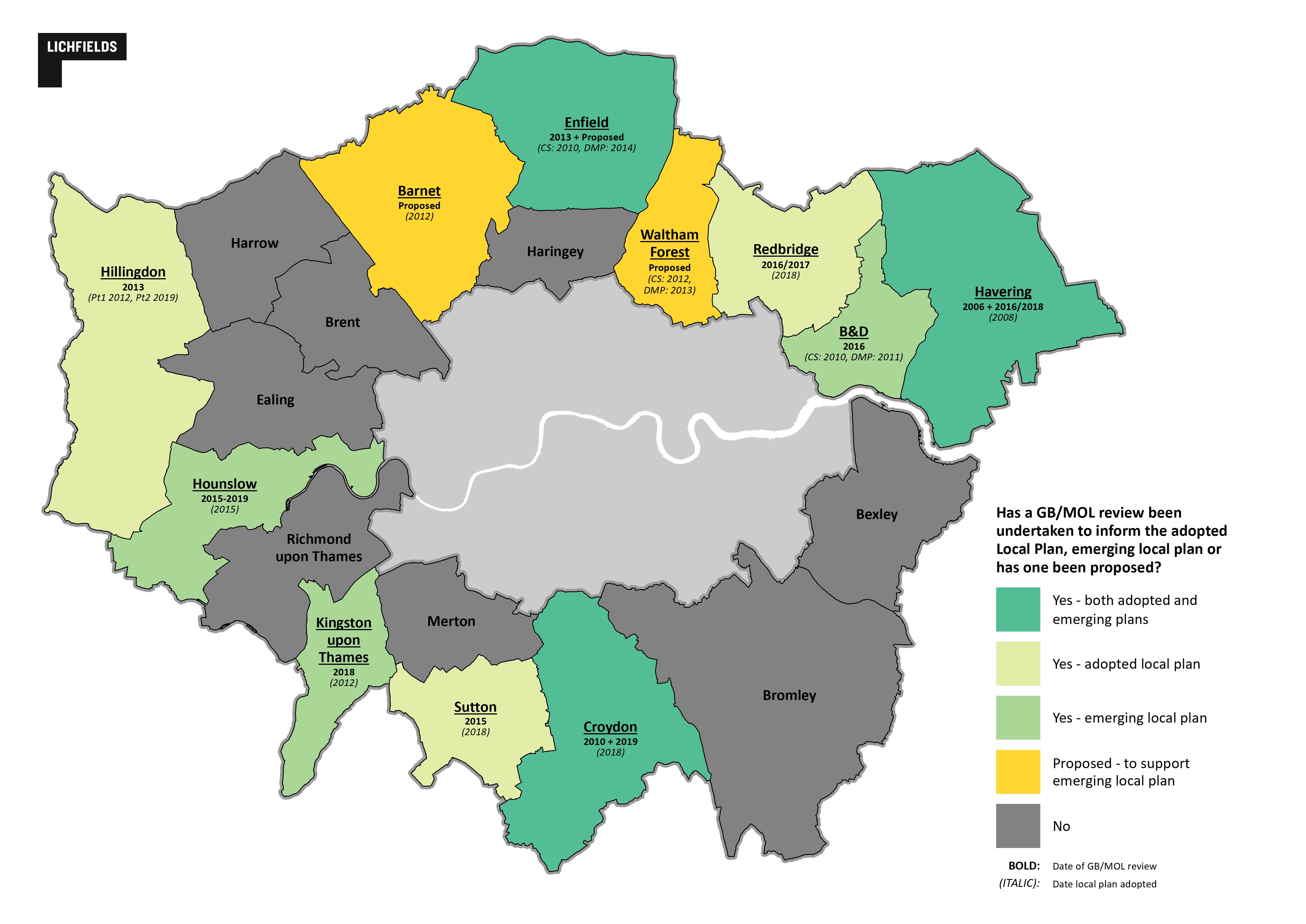

Mind the Gap). Equally, the flexibility will also allow more ambitious boroughs to consider the release of sites in sustainable locations that do not perform well against the NPPF’s criteria for designation. Our

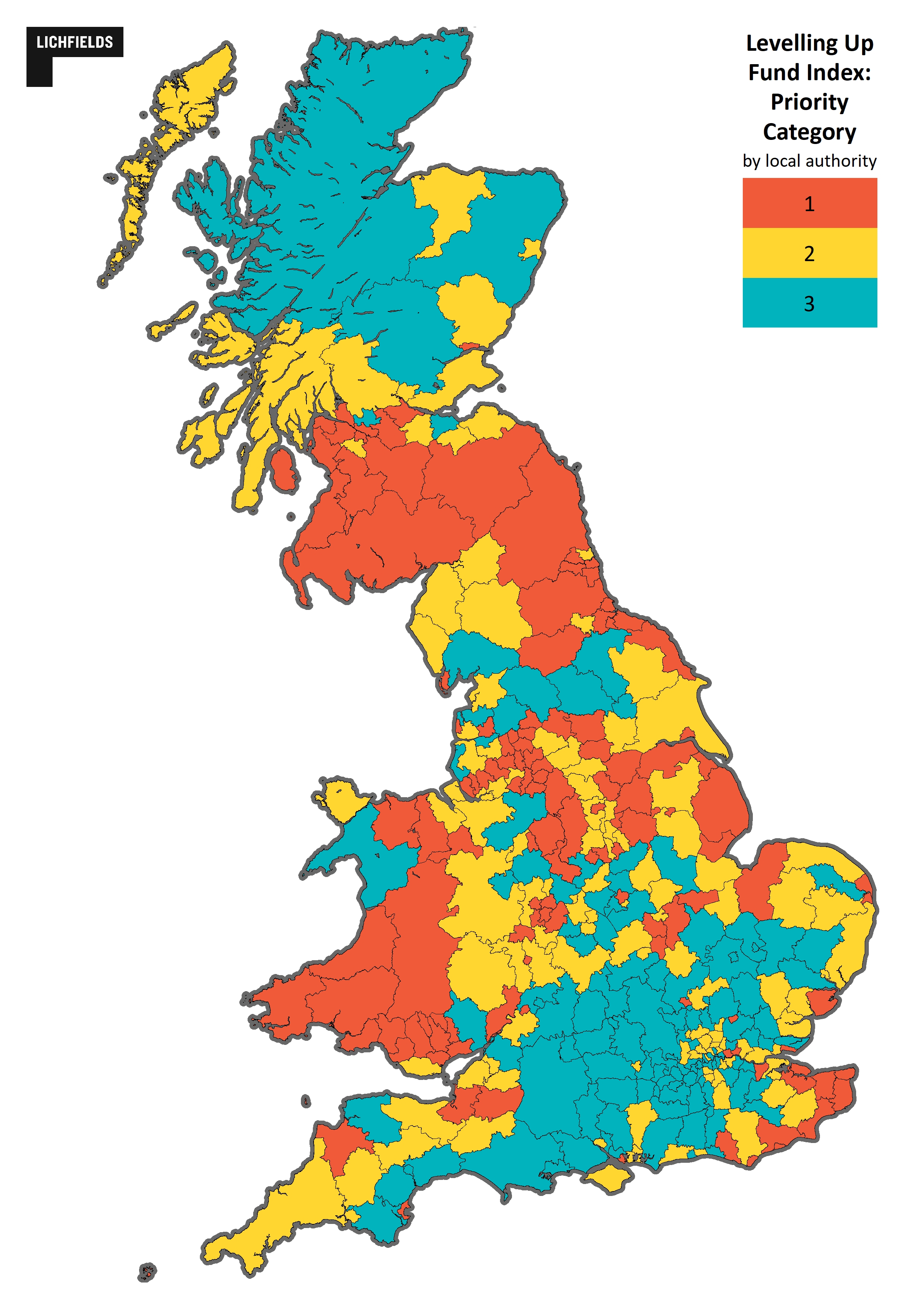

previous research on London’s Green Belt and MOL revealed that 11 boroughs had already undertaken Green Belt reviews independently of the GLA.

Source: Lichfields

With this change in policy approach, it does invite the question over whether the Mayor will continue to devolve Green Belt reviews to individual Boroughs or seek to overlap some kind of coordinated approach, following previous recommendations from the Examination in Public (EiP) Panel last December, which had suggested that a strategic and comprehensive review of London’s Green Belt should be undertaken to establish its potential for sustainable development. On balance, the former seems more likely, with the latter being a can that will be kicked down the road for the next London Plan, which will need to grapple with a sky-high housing need figure of 93,500dpa (as explored in our recent blog on the

Standard Method).

2. Land for industry, logistics and services to support London’s economy

Perhaps in light of the recent political backlash regarding other areas of planning reform (in particular, the changes to the Standard Method), the SoS’s December letter called on the Mayor to provide boroughs constrained by Green Belt and MOL with a degree of freedom to consider the release of other designated land instead, in particular, calling for additional changes to the Plan’s policies on Strategic Industrial Land (SIL).

The Mayor has revised para 6.4.8, the supporting text Policy E4, to include the following line:

“In exceptional circumstances when allocating land, boroughs considering the release of Green Belt or Metropolitan Open Land to accommodate housing need, may consider the reallocation of industrial land, even where such land is in active employment uses”.

The SoS had stated that this will “provide boroughs in the difficult position of facing the release of Green Belt or Metropolitan Open Land with a greater freedom to consider the use of Industrial Land in order to meet housing needs.” The SoS put this down to the “profound impact Covid-19 is having on London, and other towns and cities”; however, his reasoning goes no further in explaining the link, or why this is the only policy area to have been affected by the challenges of the pandemic.

Changes directed by the SoS in March 2020 had already sought a significant watering down of Policy E4 and Policy E5 and required the Mayor to drop the ‘no net loss’ principle for sites designated as SIL/Locally Significant Industrial Sites (LSIS). The additional revisions should provide boroughs with a much greater degree of flexibility as to how proposals for alternative uses for these sites are to be determined, and potential for such designations to be reviewed through a plan led approach.

The SoS was clear that the emphasis should be on ensuring boroughs “provide” sufficient land rather than to “retain” at all cost. The published Plan continues to support opportunities for intensification and co-location of uses, however, the changes directed by the SoS now actively encourage boroughs to assess the release of industrial land for alternative uses where vacancy rates are “well above the average”, where possible substituting with “alternative locations with higher demand for industrial uses”.

The EiP Panel had previously noted that that the vacancy rate of existing industrial land and premises in most boroughs is less than 5%, suggesting this sector was operating efficiently but with little capacity to meet future demands. The loosening of Green Belt restrictions may provide opportunities for SIL to be substituted outside of London’s built up areas; however, recent trends have highlighted growing demand for storage and warehousing within and close to the CAZ.

Given the current buoyancy of London’s market for industrial land, its future safeguarding and potential release for other uses will now be largely reliant on wider market factors and the viability of individual sites.

In the intend to publish version of the Plan, the Mayor did not accept the precise wording in the SoS’s direction and para 6.4.8 of the new Plan uses the following wording;

“Where industrial land vacancy rates are currently above the London average, boroughs are encouraged to assess whether the release of industrial land for alternative uses is more appropriate if demand cannot support industrial uses in these locations. Boroughs proposing changes through a Local Plan to Green Belt or MOL boundaries (in line with Policy G2 London’s Green Belt and Policy G3 Metropolitan Open Land) to accommodate their London Plan housing target should demonstrate that they have made as much use as possible of suitable brownfield sites and underutilised land, including – in exceptional circumstances – appropriate industrial land in active employment use. Where possible, a substitution approach to alternative locations with higher demand for industrial uses is encouraged”.

The wording does not contradict the SoS’s direction; but emphasises the need to make reference to other policies in the Plan and reflects para 137(a) of the current National Planning Policy Framework (albeit the draft Plan must be consistent with the NPPF 2012).

3. Optimising density

The change in approach of the new London Plan to determining appropriate densities for sites will be familiar, notably the scrapping of the density matrix and the formalising of the established design-led approach to development.

Whilst the SoS had been generally supportive of this approach, the published London Plan includes the changes directed by the SoS in December, with Policy D3 reworked so as to ensure that in optimising site capacity, development is of the most appropriate form and land use for the site and location. The Plan also includes an additional paragraph D3 (B), which clarifies that higher density developments should be promoted in locations that are well connected to jobs, services, infrastructure and amenities, by public transport, walking and cycling. Outside of these areas, incremental densification should be actively encouraged.

The approach largely echoes the Government’s White Paper which called for “

more homes at gentle densities in and around town centres and high streets, on brownfield land and near existing infrastructure”. With possible divergence in opinion as to what might constitute ‘

gentle’, some boroughs may well seek to limit development in some lower density areas. However, the GLA will likely expect this to be determined in line with its

(draft) SPG ‘Quality Homes for all Londoners’, which seeks to ensure site capacity is determined in response to the local context – an approach which accords with the recommendations of the Government’s latest guidance on design.

4. Tall buildings

Linked to the above, the new London Plan also incorporates the SoS’s directed changes to Policy D9 regarding tall buildings. The effect is a lower default threshold definition for tall buildings where no local definition is in place, reducing it from 25m in height in the Thames Policy Area and 30m in height elsewhere in London, to just 6 storeys or 18 metres across the entire Greater London area.

Essentially, unless a higher threshold has been set locally, the Plan’s tall buildings policy will be engaged for any proposals over 6 storeys tall, providing greater control over such development proposed in lower to mid-rise areas of London where local Plans are silent on the height threshold.

The December letter from the SoS acknowledged that there “is clearly a place for tall buildings in London, especially where there are existing clusters. However, there are some areas where tall buildings don’t reflect the local character”.

Taken with the directions on optimising density, these changes will give boroughs more control over applications for taller, higher density developments – perhaps in part to appease some outer London boroughs, such as Hillingdon, Bexley and Richmond, which had previously called for an approach that was more sensitive to local context. Whilst these changes may bring London closer in step with the SoS’s aspirations for “gentle density”, there is a risk this may reinforce existing patterns of low density urban form, reducing the opportunities to optimise the development potential on some otherwise sustainable sites.

5. Parking

As directed in December, the Mayor has made the changes to the maximum residential parking standards in Table 10.3, introducing a more nuanced approach for development in outer London. Where Table 10.3 provides a range, development proposals that are higher density or in more accessible locations should apply the lower of the threshold. In addition to this, the new Plan provides boroughs with the flexibility to apply higher standards in areas of outer London with the lowest PTAL rating, where there is clear evidence that this would support additional family housing (3+ bedrooms).

For retail parking standards, the Plan now aligns with the Secretary of State’s view, that boroughs may consider alternative standards in certain locations, where it can be demonstrated that the standards in Table 10.5 would undermine town centres first approach to retail development, or significantly undermine the viability of mixed-use redevelopment proposals in town centre locations.

With the Plan now incorporating these changes, it will ultimately fall to the boroughs as to how these standards will be applied. In some instances, this may assist schemes in areas with a lower PTAL, whilst also supporting the viability of mixed use redevelopment on existing retail sites and schemes and in town centre locations.

Concluding thoughts

These final revisions made in response to the SoS’s directions hand a greater degree of flexibility back to boroughs in how they plan for development, whilst decisions over how land is best utilised will be more market driven. Reflecting on the priorities and challenges of the Government’s wider agenda for planning reform, the SoS’s priorities clearly lie with delivering housing, though there is also an attempt to balance this message with assurances over design quality and the impact new development may have on lower density outer boroughs constrained by Green Belt.

On the one hand, this may support boroughs in delivering more homes, giving them greater freedom over the types and locations of sites that are considered appropriate for development. On the other, some of the changes – notably those aimed at optimising site capacity and - may reinforce existing development patterns, particularly where the surrounding context of townscape and urban character are lower in density or may be constrained in other ways.

With London delivering well below its identified housing need (now 93.5K per annum), this will almost inevitably result in the release of some sites within protected land categories, namely Green Belt, MOL, and designated Industrial Land. However, the extent to which this occurs will depend on a range of factors, not limited to the demand for alternative uses, proximity to existing infrastructure, and the viability of sites, particularly given the significant costs and limitations that often come with brownfield sites. Planning decision makers will no doubt also have regard and attach weight to the economic impact this may also have on jobs, affordable employment space, access to supply chains, storage and distribution.

The Mayor faced the difficult choice of making some relatively major concessions to his strategy or risk not getting his version of the London Plan adopted in time for the (already once delayed) Mayoral elections in May.

While both the SoS and Mayor had agreed that getting the new London Plan adopted would be critical in providing the certainty and strategic direction needed for London’s recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, the comments in the SoS’s most recent letter indicate he is far from satisfied with the ambition and direction of the Mayor’s strategy for London. On reminding the Mayor that he has powers to order either a review or alterations to the London Plan, the Secretary of State commented:

“Notwithstanding the above you still have a very long way to go to meet London’s full housing need, something your plan clearly and starkly fails to achieve. Londoners deserve better and I will be seeking to work with those ambitious London Boroughs who want to deliver over and above the housing targets you have set them”.

The SoS is clear that moving forward he expects the Mayor to “dramatically increase the capital’s housing delivery”, with the next London Plan expected to fill the significant gap between delivery and housing need. The letter states the SoS wishes to work with “ambitious London Boroughs who want to deliver over and above the housing targets”.

The Plan’s publication marks an important milestone for planning and development within the capital. It will be interesting to see what shape and form the next London Plan (and other Spatial Development Strategies) will play, given the potential wider reforms as outlined in the Government’s White Paper.

Mayor of London, Publication London PlanSecretary of State Robert Jenrick's letter to Mayor, 24 December 2020