Of course, as you would expect, we did spend some time analysing what has led to the current crisis on the high street – a ‘Perfect Storm’ created by the untimely collision of a range of factors:

-

The march of technology – smart phones and other technological advancements have made internet shopping ever more convenient;

-

A greater consumer focus on convenience;

-

A decline in consumer loyalty – both in terms of individual brands and shopping locations; and

-

Increased interest in experiences– in preference to material goods, and in subscription services over products.

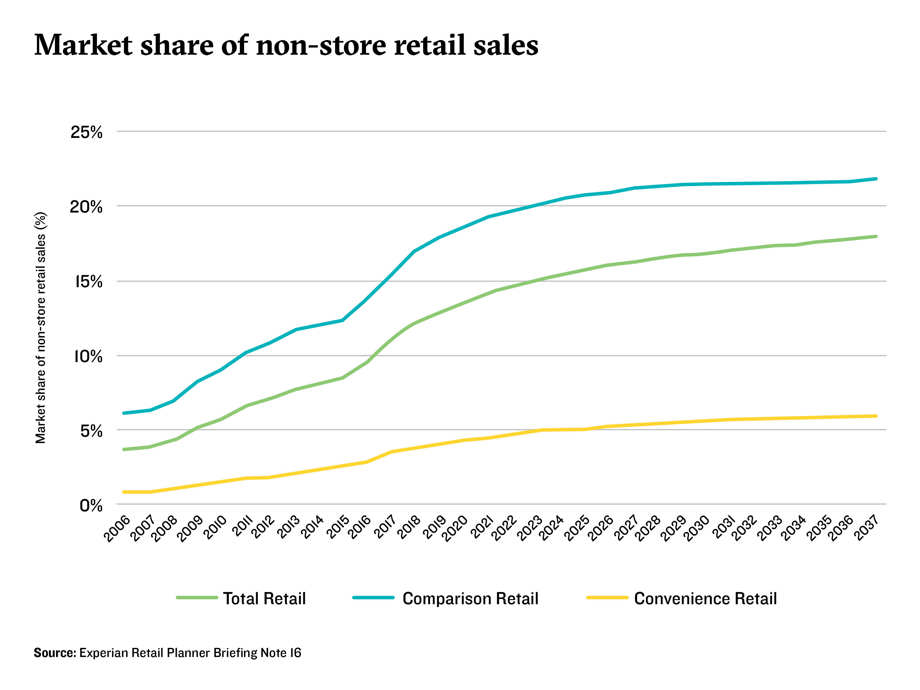

We also spent some time discussing the ‘elephant in the room’ – the growth in online shopping – which has undoubtedly been a key driver of change and one which shows no sign of abating with growth set to continue (albeit at a slower pace) for at least the next decade. There is no question about it – online retailing is still growing and is here to stay.

- In most centres ‘do-nothing’ isn’t an option – given the extent of the structural change currently being experienced, a ‘do nothing’ approach won’t work and except perhaps in the very strongest locations, we aren’t going to able to rely on retail demand to fill the space in our centres – put simply, many centres now have an over-supply of Class A1 and A2 retail floorspace. Weak values in many centres will undermine the viability of redevelopment options in many centres, and ‘re-purposing’ existing spaces to meet occupier demand and current and future needs will be key.

- Despite the doom and gloom, some sectors are growing – while retail demand has unquestionably fallen, there are still some A1 retailers with live requirements for new floorspace. In addition there is increased demand in many centres for town centre pubs / bars, gyms and health clubs, and retail services such as hairdressers, beauty salons, dentists / orthodontists – typically the things we can’t buy on-line. Some of these uses were previously ‘priced out’ of town centres but are now finding opportunities to take space due to the fall in rental values. In addition, some retailers (e.g Primark) are continuing to thrive despite no on-line sales presence.

- Multi-Channel retailing is an opportunity, not just a threat – the internet is here to stay and it has clearly impacted on shopping patterns and will continue to do so. However, multi-channel retailing and ‘click and collect’ in particular brings opportunities to attract new customers into town centre environments – and customers using ‘click and collect’ facilities are quite likely to spend money on other goods and services when they come into town to collect goods bought online. Social media channels such as Instagram also provide new opportunities to engage with and attract customers e.g through the role of on-line social media ‘influencers’ and their ability to promote in-store events.

- Town Centres need to be customer-focused – if centres are to be successful, there needs to be an increased focus on the needs and wants of customers – and the overall experience they offer. Factors like toilet provision, perceptions of safety, cleanliness, lighting, disabled access, evening opening hours, accessibility and parking all make a big difference to how people view town and city centres, and ultimately influence how often and when they choose to visit. The most successful centres will be those that understand this and develop strategies to ensure that the overall customer experience is positive and encourages return visits.

- Local authorities have a central role to play – whether through business support, car parking, planning policy strategies or development management decisions, local authorities have a key role to play in driving the success of town centres. Those authorities that take a positive and pro-active planning strategies to ensure centres can both evolve and attract new investment (e.g through changes of use away from A1 retail to a broader range of uses, and through new office and residential development), and through support for independent businesses, will create the platform for success.

- Business also needs to play its part – Notwithstanding the need for local authorities to create the platform for success, business also needs to play its part. All town centre businesses have an interest in the success of the centres in which they are located but business engagement and collaboration in town centre strategies and initiatives is often poor. Through active participation and leadership, national and local / independent businesses need to step up and play full and active roles as stakeholders in centres.

- The need for Town Centre Management remains as great as ever – while the funding / resource environment may be difficult – local authorities budgets are tight and in contrast to the 1990s, few national retailers actively support town centre management posts and initiatives – the need for management of our town centres is probably greater now than it has ever been.

- There are a wide range of planning tools available to support town centres – planning policy has a role to play and while national planning policy, as set down in the NPPF appears unlikely to be tightened in the near future, there are many existing planning tools which LPA’s can use to support and regenerate town centres. Compulsory purchase powers, Local Development Orders, Neighbourhood Development Orders, Area Action Plans, Supplementary Planning Documents, Business Improvement Districts, Heritage Action Zones and Development Corporations provide local authorities with a multitude of different options, which are not currently being fully explored.

- Town centres need to remain relevant to the communities that they serve – people have more choice in retail and leisure than ever before and we need to give them reasons to choose town centres over the myriad of other options available.

- Town centres remain an important element in our local economies - even if total employment in the retail sector has fallen recently, it remains a hugely important sector within the economy. The latest available ONS data confirms that 9.5% of the total working population in England is employed in the retail sector – equating to around 2.5 million people. Only the healthcare sector employs more people nationally. This shows the value in supporting town centres from an economic perspective.

Image credit: Orange "Pip" market (Middlesbrough Council) After years of focus from the Government and the built environment profession on other issues, the high street is finally climbing up the agenda. An expert panel was set up at the request of the High Streets Minister (Jake Berry) in July 2018, culminating in the publication of the High Street Report in December of that year. The Government then published its own response to a Select Committee inquiry in May 2019. As part of this, they announced a review of the Use Classes Order and number of changes to Permitted Development Rights (including changes of use), which my colleague Dan Gregg will cover in a separate blog next week.

Here in the North East, we recently took part in a research project with the North East of England Chamber of Commerce (NEECC). This project developed a series of recommendations to help town centres ensure their future roles, based on research and examples of best practice, focused around workshops with key stakeholders in five city/town centres. The report can be found here and while it is based on experiences in the North East, the recommendations from the research will be relevant to many centres around the UK.

In summary, town centres do have a future, but it will be a little different. In many cases, they might not look radically different from the way they look now – they will offer less retail floorspace, but also a wider range of other uses including a stronger independent offer, and they will be supported by increased footfall from office workers and new residential communities. Fundamentally, to be successful, centres need to be relevant to the communities that they serve – and they will need a lot more love than we show them now.