The current crisis has inevitably meant even more headlines declaring the 'death of the High Street' in the press and amongst some property people. There are huge challenges ahead but we are at a pivotal moment. The gravity of the situation we currently face is going to mobilise energy, dynamism and innovation like never before, such that the rebound - when it comes and it will take some time - will bring a genuinely new and positive future for many of our town centres.

This is the first in a number of blogs about the future of the High Street and I start with where we are now, in the middle of a crisis.

The bad news is well trodden ground already and the situation is going to get worse before it gets better. Many town centre businesses are in distress, some have gone to the wall already and more will follow in the coming weeks and months. Landlords are faring no better; everyone is facing up to the reality of a long phased exit strategy including a lingering fear pervading amongst the population until a vaccine eventually appears.

So what is there to be positive about? Plenty in my view if you look carefully at what is stirring and it starts at the top.

Up until about two years ago the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government were only really interested in planning for more homes and they didn't concern themselves that much with the potential of town centres contributing to that very important policy agenda. Thankfully things have now changed - the Government is engaged and the problems we now face should only increase the funding and resources that will be made available in the future. Putting this together with the levelling up agenda will mean more centres will benefit and there will be a better spread of investment than ever before. It might also be that the business rates holiday handed down to mitigate the effects of Covid-19 will herald much needed wholesale reform in that area, a longstanding ask of the industry.

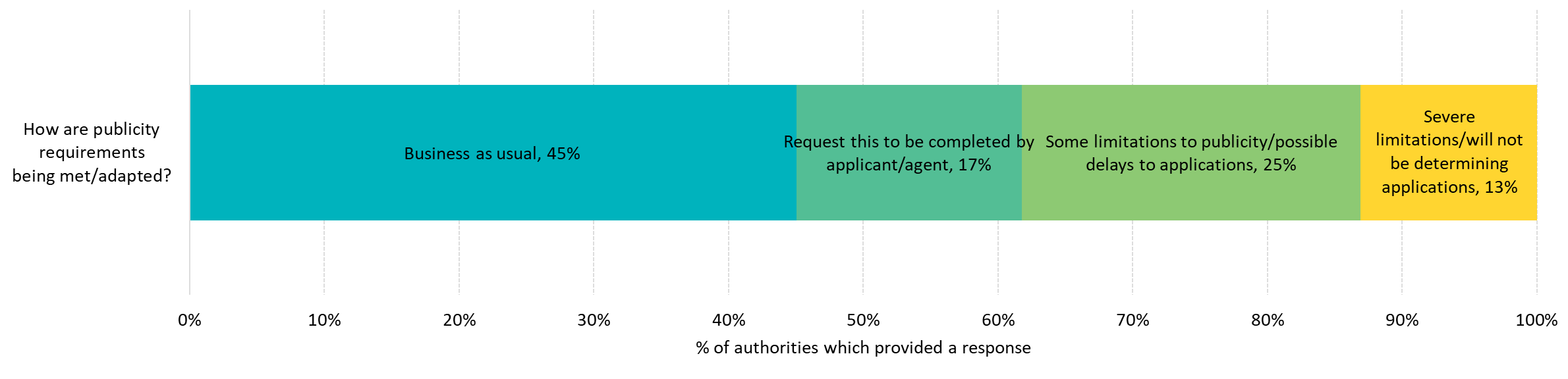

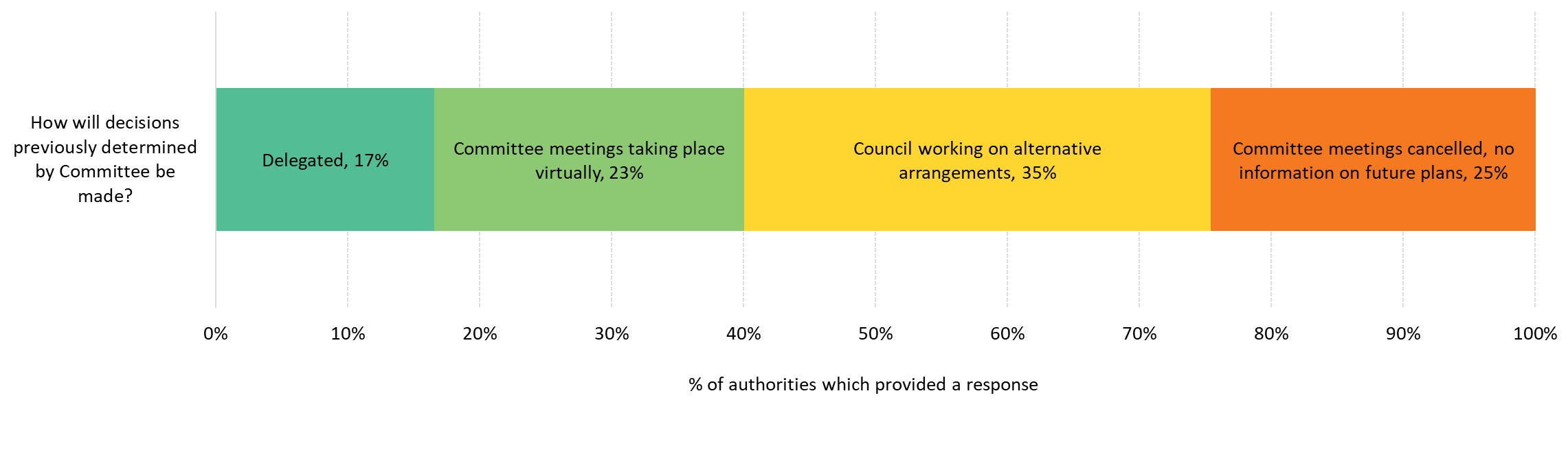

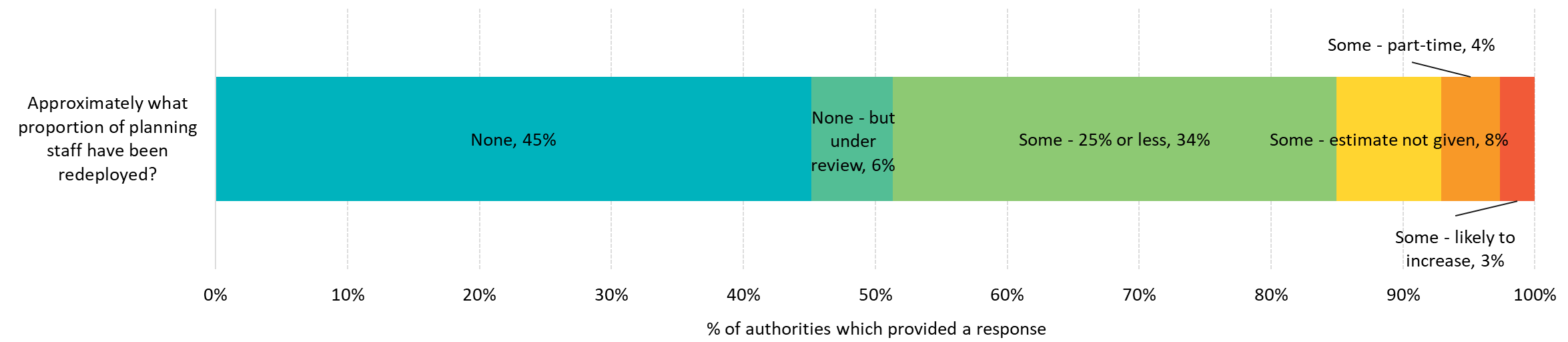

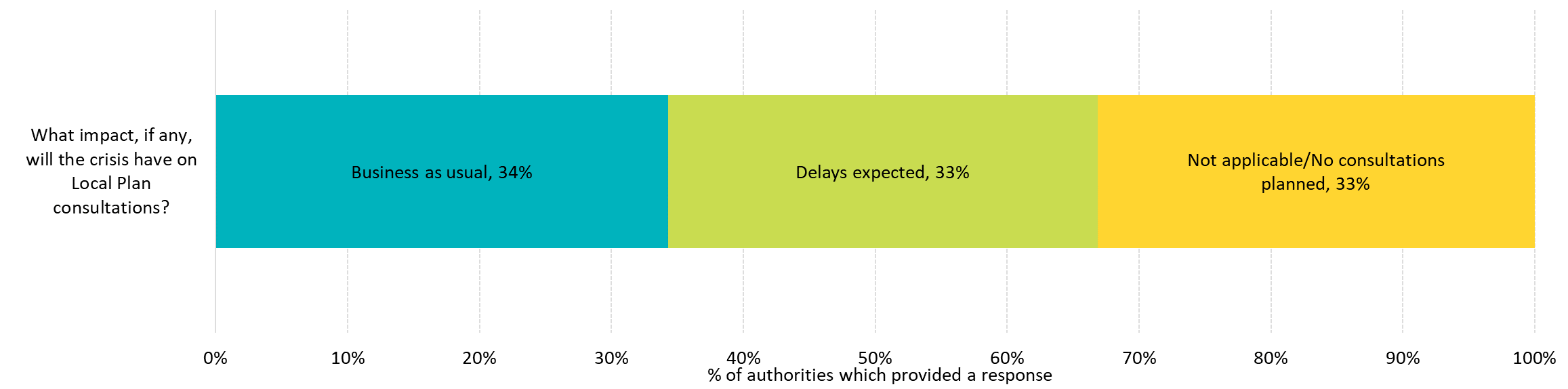

At local level we are seeing a tremendous response from many local planning authorities to Covid-19. Our Business as (un)usual live web tool gives up to date information about how over 90% of local authorities are responding to the challenges they face undertaking pre-application and decision-making processes, amongst other things, at the current time. Some are struggling with a lack of IT investment following cuts to budgets; others are requisitioning planning staff to work closer to the frontline, dealing with such things as business rates and supporting small businesses on the High Street by providing training on selling their products via on-line platforms to create new income streams whilst their shops are closed.

I am an independent member of the Planning Decisions Committee at the London Legacy Development Corporation and was involved in its first virtual committee meeting earlier this week. The Corporation is not covered by the Government's emergency legislation but no matter; urgency powers were invoked and decision-making authority was vested in the chair, informed by discussion with committee members. There were presentations from officers and public speakers, all curated via Skype for Business. No committees have been missed so it's (almost) business as usual and this is critical to ensure that those developers proceeding with schemes are not held back.

What we are seeing is more of the best of what local government has to offer. At a time of adversity we see new leaders come to the fore, driven by a strong sense of duty to do all that’s required to help those in need. Economic development departments are all hands to the pump and we have seen strong interest in our Covid-19 Economic Risk Index as minds turn to future investment planning. With town centres very much in the policy spotlight and money available from Central Government we will see this vigour carried forward in the planning arena. More action plans and investment plans will emerge and we will see a new wave of development coming forward when market conditions improve.

What form that development will take brings me on to the last matter for this blog. Despite the decline of retail in recent years the value - actual and perceived - wrapped up in shops and the car parks that serve them has been a barrier to re-development with appraisals having to deal with very large negative starting points. But the balance has now tipped. Just as the decline in retail values shows no sign of abatement the fundamental shortage of new homes will underpin demand, and values, in the residential sector, even if recession remains a short term challenge. Shopping centres are of increasing interest to residential and mixed use developers and local councils. Retail uses will shrink to a more sustainable core offer, a wider variety of commercial and community uses will be intertwined and new homes will sit on top and around them. But there will be regional variations and different strategies for different centres. In town centres where there is no market for residential development, we should plan for a renaissance in start-ups and independent businesses combined with the re-purposing of existing space and improvements to the public realm and basic infrastructure.

The commercial property industry is currently taking a massive kick in the teeth and its focus is necessarily a short term one overcoming an unprecedented situation. Representative organisations are representing their members and lobbying Central Government hard, with a noteworthy recent proposal by Revo, the British Property Federation and the British Retail Consortium for a Furloughed Space Grant Scheme (where the state would cover the fixed costs of businesses that have experienced falls in turnover), having received much publicity.

Just as there have been major challenges for local government over the last decade responding to massive cuts in their budgets, the property industry will need to strike out of its segmented silos, cross-fertilise knowledge and ideas, and rise to the epic challenges our town centres face and seize the opportunities that always arise out of adversity. There is hard work ahead but the High Street certainly isn’t dead; long live the High Street.