The new government has hit the ground running when it comes to changing the previous government’s policy approach to housing delivery. In this blog, I explore what these changes will mean for the West Midlands.

The introduction of the National Planning Policy Framework’s [NPPF] standard method [SM], and subsequent revision in December 2020 with the introduction of the 35% urban centres uplift, raised some practical issues for the delivery of housing across the West Midlands.

For many local planning authorities [LPAs], the current method generated housing need figures lower than the adopted Local Plan requirements, often suggesting fewer homes than historically built. The current method would increase the housing needs in the West Midlands by about 30% compared to the adopted plans, driven largely by Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton being subject to the urban centres uplift, rather than the other LPA's needs increasing. However, there were also concerns in the region that relying on the 2014-based household projections was inappropriate (e.g. Coventry), but this will change as the proposed new SM moves away from this, towards a stock-based approach – we have set out a blog explaining the new SM in detail

here.

The West Midland’s new standard method figures

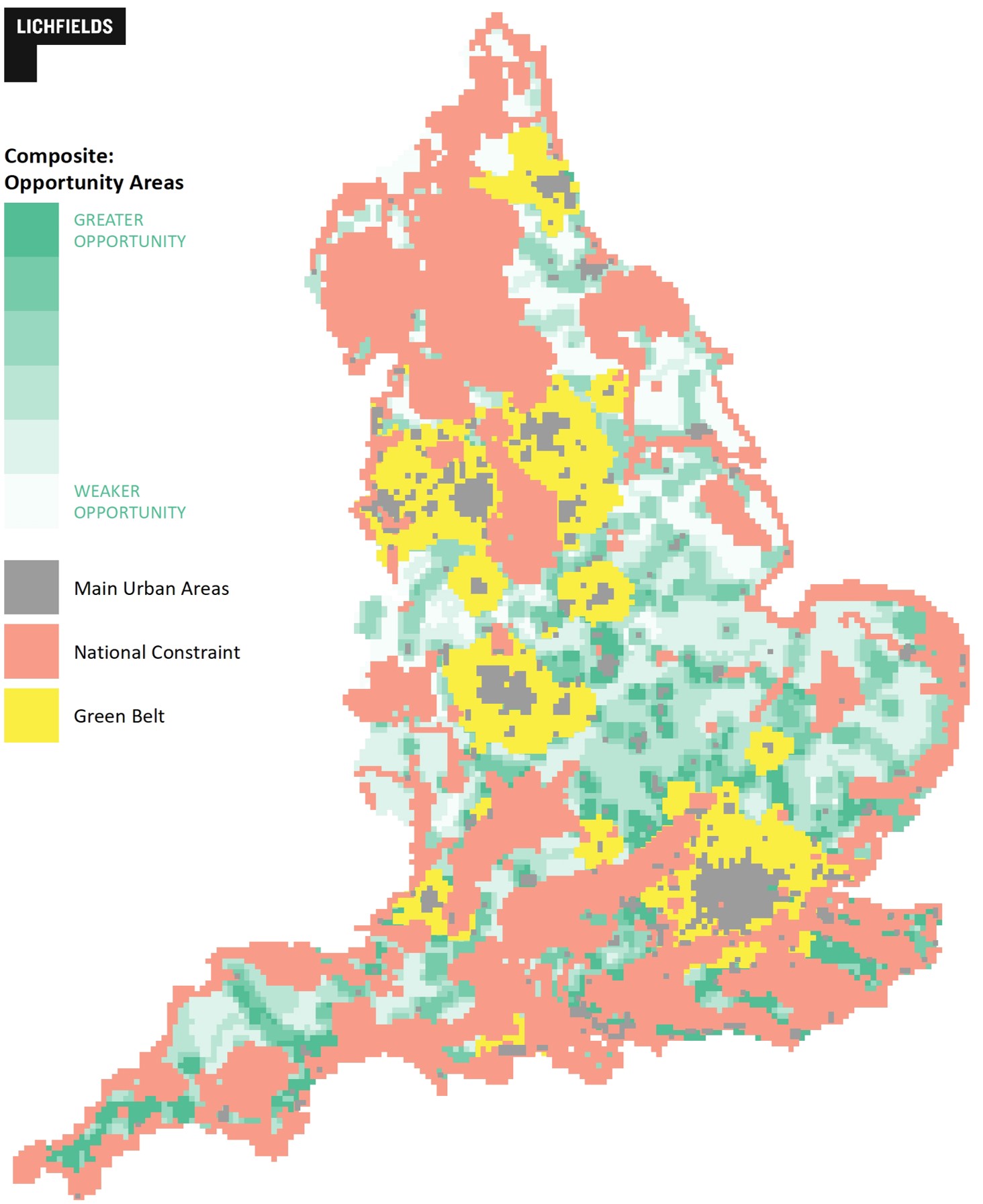

What are the implications of the Government’s proposed new standard method for the West Midlands? Lichfields has examined the new local housing needs figures for all West Midlands LPAs under the proposed method, including average delivery rates over the past three years and compared these with the current method's figures. These are shown in the map below:

Percentage change between current SM and proposed SM

Source: Lichfields analysis

Most interestingly, 90% of West Midlands authorities will see an increase in their Local Housing Need [LHN] figure under the new method; save for Birmingham, Sandwell, and Coventry who will see a decrease due to the removal of the 35% urban centres uplift. Despite these decreases, the West Midlands would be expected to deliver 31,751 dwellings per annum, a c.28% increase compared to the current method, amounting to a 47% boost over recent delivery levels.

The chart below shows the spatial distribution of housing needs across the region compared to the current method. The new method significantly impacts rural LPAs adjoining Birmingham, Coventry, and Worcester, especially along the southern edge. The Black Country also sees a notable increase, with Dudley’s housing needs rising by 143%. Most authorities would see increases between 50%-99% and 100%-150%, whilst five authorities would experience a rise exceeding 150%, a marked increase.

West Midlands Comparison of Housing Needs

Source: Lichfields analysis

A sub-regional challenge

The main conurbations of Birmingham, the Black Country and Coventry have experienced longstanding issues arising from their tightly drawn boundaries, which when coupled with Green Belt constraints, has led to issues of unmet housing needs across their respective housing market areas [HMAs]. This was further compounded by the 35% urban centres uplift. Looking more specifically at these issues under the new SM, the proposed new method will lead to some significant implications for plan-making over the next two to three years.

1. Greater Birmingham and Black Country

The housing needs of the Greater Birmingham and Black Country HMA

[1] [GBBCHMA] have long been a subject of debate, which has largely revolved around Birmingham and the Black Country being unable to meet their housing needs. This challenge looks set to continue. The chart below compares these requirements across the GBBCHMA’s.

The new SM would result in Birmingham’s needs being reduced by c.31% compared to the current SM, which is likely to reduce their emerging shortfall of c.46,000 dwellings. In contrast, except for Sandwell, the Black Country authorities [BCAs] would see their needs increase – even with the removal of the urban centres uplift from Wolverhampton. This suggests that the BCA’s emerging unmet housing needs up to 2038 will persist and remain a critical issue for the GBBCHMA authorities to grapple with, alongside their own needs, through their current Local Plan Reviews.

Similar to the regional trend, a majority of the GBBCHMA would see significant increases in the number of houses they should be planning for under the new proposed SM. The most significant increases are expected in South Staffordshire, Tamworth and Redditch. Given the tightly bound nature of the latter LPAs, it is very possible that they will struggle to meet these needs in full, suggesting that other LPAs within the GBBCHMA may also report unmet housing needs as they progress their Local Plans.

GBBCHMA Comparison of Housing Needs

Source: Lichfields analysis

2. Coventry-Warwickshire

Across the five authorities which make up the Coventry-Warwickshire Housing Market Area [C&WHMA],

[2] LHN figures would significantly increase under the proposed new SM. In absolute terms, Warwick and Stratford-on-Avon would see the most dramatic increases when compared to the current method. However, whilst the proposed new SM for Warwick would be well in excess of the level of delivery seen over the past three years, for Stratford-on-Avon, the proposed new SM would actually be c.190 dpa lower per annum than the level of delivery seen over the last three years. In percentage terms, North Warwickshire would see its LHN figure increase by 133% – the highest increase within the C&WHMA. This would be much lower than the adopted housing requirement; although it is noted that this requirement contains unmet need contributions to both Coventry and Birmingham in addition to their own needs.

As expected, the housing need of Coventry would decrease as a result of the removal of the 35% urban uplift; although this would still be c.300 dpa higher than the adopted housing requirement, and would equate to a c.22% increase in need when compared to the level of delivery achieved over the last three years. Given the Council’s emerging land supply, the city could still place pressures on the surrounding Warwickshire LPAs to accommodate its unmet housing needs.

For Nuneaton & Bedworth, the proposed new SM would result in an LHN c.42% higher than their emerging Local Plan requirement – which is currently at EiP – which was already higher than the current SM-generated LHN. Given the transitional arrangements – which I discuss below – they may well need to consider whether their emerging Local Plan will require a review post-adoption, in advance of the statutory five-year requirement, and under the new style Local Plan system.

C&WHMAComparison of Housing Needs

Source: Lichfields analysis

3. An emerging challenge for strategic planning

Alongside the Government’s consultations on the NPPF and new SM, they are also consulting on other changes to the planning system. As a part of this, Combined Authority Mayors will be expected to prepare Strategic Development Strategies, which will include a requirement to meet the cumulative housing needs of the authorities within the Combined Authority’s administrative area.

For the West Midlands Combined Authority [WMCA]

[3] the new SM would result in a 12% reduction in housing needs across the WMCA when compared to the current SM. Despite the marked increase in the needs within the Black Country, these are more than offset by reductions in the LHNs for Birmingham and Coventry. But with 6 of the 7 constituent authorities tightly bound, or with limited opportunities to expand even with Green Belt release, the WMCA may need to look to the non-constituent authorities

[4] and beyond

[5] to meet any unmet housing needs arising through the current round of plan-making.

The key to unlocking this challenge may be to instigate a regional approach to Green Belt review and release, and retain an effective Duty to Cooperate (or a future iteration) to secure agreements on distributing any unmet housing needs in the WMCA and beyond – both of which are strengthened by the proposed changes in the draft NPPF in respect of

strengthening obligations on cross-boundary working and

Green Belt release.

How soon will these needs impact on planning?

1. Plan-making

Alongside the consultation on the proposed changes to the SM, the Government has also published a draft NPPF. In this, it is seeking to introduce transitional arrangements in respect of plan-making to address the housing needs generated by the proposed new SM.

These are set out in paragraphs 226-229 of the consultation document and will apply from the adoption of the revised NPPF in Autumn 2024 plus 1 month. Simply put, they require that any LPA at the Regulation 18 stage of Local Plan preparation will need to immediately utilise the new SM for plan-making purposes and any LPA at the Regulation 19 stage whose emerging requirement is more than 200 dpa lower than the new SM will need to update and submit their emerging plan within 18 months of the adoption of the revised NPPF to address the new SM alongside any other new requirements from the revised NPPF. Even LPAs that have submitted their Local Plans will need to address their new SM needs in short order, where the adopted requirement is 200 dpa lower than the new SM via beginning a new-style plan immediately post-adoption. This is a challenging requirement and will place significant resource pressures on the LPAs affected.

Inevitably, the proposed new standard method will have immediate, and profound, implications for plan-making across the region. Despite LPAs across the region having progressed their Local Plan reviews, many will now need to revisit their proposed spatial strategies, and Green Belt assessments, and seek to markedly increase their proposed housing delivery numbers.

Based on Lichfields’ understanding of the region's current position on plan-making, and assuming the constituent LPAs follow their stated timescales for preparation, as of Autumn 2024, of the 26 LPAs undertaking reviews, some 18 plans that are at the Regulation 18 stage will need to factor in a higher LHN figure as a minimum. One plan, which is significantly advanced, will have 18 months from Autumn 2024 to re-visit their Local Plan proposals to address the increased housing needs. By way of example, assuming South Staffordshire adheres to its Local Development Scheme timescales (i.e. a January 2025 submission), it will need to revisit its Local Plan review to accommodate an additional 449 dpa – no small feat. Even authorities with a submitted plan may soon need to consider starting the process again. In summary, the new SM will impact most of the region's local authorities immediately, and within 2-years for the rest in terms of plan-making. The spatial implications of the transitional arrangements are depicted below.

Transitional Arrangements – Impact on plan-making

Source: Lichfields analysis

2. Decision taking

In the NPPF consultation, it is proposed to return to the previous governments’ (September 2023) NPPF’s approach to the requirement for LPAs to demonstrate a five year housing land supply (“5YHLS”). To this end, for those authorities whose Local Plan is over five years old and has not been updated, for the purposes of a 5YHLS, the housing need will be measured against the area’s LHN, calculated using the standard method.

This means that whilst some authorities may not need to grapple with the increase in housing through a Local Plan for c.18 months to 2 years, there may be an immediate impact on planning decision-taking due to that Council’s ability to – or not in some instances – demonstrate a 5YHLS in the context of planning application determination.

Lichfields estimates that just over three-quarters of LPAs in the West Midlands will see immediate impacts on their 5YHLS as of 1st November 2024. On average, the increase in housing needs resulting from the changes to the SM over a five-year period would equate to each of these LPAs needing to deliver an additional 2,092 dwellings on average (exclusive of buffers).

It’s not only the LPA with significantly less than a 5 year supply of housing that will suffer, even those authorities with relatively strong housing delivery may find themselves susceptible to decisions influenced by the

‘tilted balance’ mechanism. When this concern is coupled with the draft NPPF’s proposed changes to Green Belt policy, it will be in the interests of some LPA’s to progress their Local Plan reviews as quickly as possible. Overall, LPAs will be advised to carefully consider the implications of the new SM and its impact on their 5YHLS as a matter of urgency.

Transitional Arrangements – Impact on decision-taking

Source: Lichfields analysis

Summary

The significant increase in housing needs across the West Midlands under the proposed new SM will inevitably once again raise legitimate and cogent arguments about the availability of brownfield land and the need for Grey Belt/Green Belt release, in order to ensure sufficient land is available to deliver the homes that are needed. Consequently, the debate around where such land is to be found, alongside how these needs can be distributed across the West Midlands HMAs, looks set to continue for the foreseeable, but will at least operate under a framework that sets clear expectations on how this should be achieved (i.e. effective cross-boundary engagement and Grey Belt/Green Belt release).

[1] Comprising Birmingham, Bromsgrove, Cannock Chase, Dudley, Lichfield, North Warwickshire, Redditch, Sandwell, Stratford-on-Avon, Tamworth, Walsall and Wolverhampton; albeit, North Warwickshire and Stratford-on-Avon fall within the Coventry-Warwickshire HMA.

[2] Comprising Rugby, Coventry, Warwick, North Warwickshire, Nuneaton and Bedworth and Stratford-on-Avon

[3] Comprising: Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, and Walsall

[4] Comprising: Cannock, North Warwickshire, Nuneaton & Bedworth, Redditch, Rugby, Shropshire, Stratford-on-Avon, Tamworth, Telford & Wrekin, Warwickshire County

[5] E.g. Lichfield, Wyre Forrest, South Staffordshire, Warwick etc.