Update 22 December 2022: The Government has now published a consultation that advances the plan-making proposals in the Bill and the policy paper published in May 2022; Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill: reforms to national planning policy

The Planning White Paper (2020) saw the Government propose major changes to the planning system, with a focus on increasing the delivery of new housing, while ensuring new development would be well-designed and accompanied with the necessary infrastructure.

Reforming the role and nature of plan-making was a key component to achieving these objectives. As a recap, the White Paper proposed that all local planning authorities (LPAs) must have up to date plans in place, while plans themselves would be shorter, simpler, and more effective. Generic development management policies would be set out in national policy, while the number of homes that LPAs should plan for would also be determined centrally. A zonal approach to planning (of sorts) was also proposed, with all land designated for growth, renewal, or protection. Local plans were to focus on setting out detailed area and site-specific requirements, making use of web-based policy maps with design codes setting out detailed design requirements for key character areas.

Almost two years later and after a huge amount of speculation as to the shape and extent of the reforms, the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill has landed. Further changes to national policy and detailed regulations are expected to come, with an overview of these (relatively substantial) changes set out in an accompanying Further Information policy paper. While the proposals for ‘zoning’ have been abandoned, and the details of a new standard method remain to be seen, many readers will be surprised at how much of the 2020 White Paper may be set to come forward.

This blog focuses on the changes to development plans put forward by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC). Please see our other

blogs which cover the other areas of planning reform and regeneration set out within the Bill.

The development plan – a change in status?

The Secretary of State will now write National Development Management Policies. The purpose of this is to reduce the size of plans by removing generic development management policies which are largely the same across England, hopefully leading to greater consistency as to how these are applied in practice.

The starting point for decision making, s38(6) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 (PCPA), would be revised under the Bill, fundamentally changing the way planning decisions are made, by inserting the word “strongly”. Where determining applications for planning permission, decision makers would now have to give regard to the “development plan and any national development management policies, unless material considerations strongly indicate otherwise" (our emphasis). The potential policy and legal implications – intended or otherwise - of the introduction of “strongly indicate otherwise” will no doubt be discussed at length during the passage of the Bill. The Bill states that, where there is a conflict between a policy in the local plan with a national development management policy, primacy would be given to the national development management policy.

The changes would give greater weight to the development plan than is currently the case, while also immediately elevating the status of national development management policies above other national policy. These national development management policies, as directed by the Secretary of State, would not be a

material consideration, but would have the same weight as development plan policy. It is not yet clear what matters these national policies would cover, though heritage, Green Belt, and environmental policies such as Biodiversity Net Gain seem like possible contenders. It is also unclear as to what might be

“strong reasons to override the [development]

plan” [1].

The Government has said it will set out a new vision for the NPPF, “detailing what a new Framework could look like, and indicating, in broad terms, the types of National Development Management Policy that could accompany it”. This might see the NPPF being broken up into two distinct sections, with one section setting out specific development management policies designated as part of the statutory development plan, and other parts setting out national policy on plan-making, which would remain a material consideration.

Getting local plans in place… and keeping them up to date

Despite local plans currently being the starting point for decisions, recent research from

Lichfields has revealed that only 42% of LPAs outside of London had a fully up-to-date local plan to the end of March 2022. The Government expects that shorter, simpler plans will vastly increase number of LPAs with sound plans in place that are also kept up to date.

The Bill’s

Further Information policy paper confirms that local plans will need to be prepared within a 30-month timeframe and will be expected to be updated at least every five years. Given the lengthy timescale it currently takes for plans to be prepared (74 LPAs have not adopted a local plan in the ten years since the NPPF was first published in March 2012), many (including the

LUHC Select Committee) questioned how achievable this timeframe was when the White Paper was originally published.

It may be more realistic than when proposed in the White Paper, because plan-makers will not need to contend with dealing with the zonal system the White Paper proposed. Furthermore, the existing Duty to Cooperate is expected be dropped (more below). In its response to the Select Committee’s report the Future of the Planning System, the Government has said it will also seek to “reduce the evidence burden”, as well as changing the “soundness tests at examination”. The detail of these additional changes is expected to be set out in regulations.

No details have yet been published on the new standard method for assessing housing need. Understanding how this will be calculated will be crucial to the success of any future changes to the plan-making process. Allocating land for housing is a fraught process, with arguments over the suitability and deliverability of sites taking a considerable amount of time during preparation and examination of plans. The issue is particularly acute in parts of the country where land is constrained by environmental protections or Green Belt policy, which has often led to stalled plans as a result of difficult local politics, which subsequently effect the delivery of new housing and development (see our

recent blog for more detail).

Another major change is the Government’s intention to remove the requirement for LPAs to maintain a five-year supply of (deliverable) land for housing, providing the LPAs local plan is kept up to date. As it stands, failure to demonstrate a five year land supply (with an appropriate buffer) has led to the operation of the presumption in favour of sustainable development regardless of the local plan status of the authority, leading to many LPAs with up to date local plans also failing to demonstrate a five year land supply and the presumption applying accordingly.

The Government appears to intend this change as a carrot to encourage LPAs (particularly long term avoiders) to get their plans up to date and adopted quickly. However, many long term avoiders of plan making are Green Belt constrained and without a change to Green Belt policy (including very special circumstances) there remains little incentive for them to adopt a local plan - even with this carrot.

Strategic thinking - Joint Spatial Development Strategies

As mentioned above, the Government wishes to abandon the Duty to Cooperate, the legal obligation introduced via the Localism Act 2011 that requires cooperation between LPAs. Instead, new powers are proposed that would allow for at least two LPAs to produce a joint spatial strategy. This would have a similar effect to strategic role to the London Plan, albeit across much smaller geographies.

Given that the proposed Joint Spatial Development Strategies are voluntary, some will question how many LPAs will choose to adopt this approach, particularly where this may require an LPA to take on the unmet need of its neighbours. That said, in areas with ambitions for growth, this could be an important tool, providing the necessary governance and decision making powers to make difficult choices on infrastructure and other cross-boundary issues - particularly if supported with financial incentives or other powers.

Lichfields’ own

research on the future role of Spatial Development Strategies (SDS) suggests that the London Plan has played a critical role in leading growth, while helping to secure important decisions on the future direction of travel in the capital. At the same time, the Mayor has also faced accusations of over-reach, with the latest London Plan interfering in matters deemed as non-strategic. Interestingly the Bill appears to have responded to this criticism, with proposed changes to the GLA Act 1999 to make it more explicit in defining the remit of SDSs.

Supplementary plans and area-wide design codes

The Bill would also provide greater flexibility as to how local policy can be brought forward. The Bill proposes a new power for LPAs to prepare ‘Supplementary Plans’, enabling a lighter touch route for LPAs wishing to introduce policies relating to specific sites, types of development, and for adopting local design codes.

During a briefing on the Bill to the planning and development sector by DLUHC, Director of Planning, Simon Gallagher, suggested that this would remove some of the ambiguity of supplementary planning documents, which do not carry the same weight as policy (sometimes leading to confusion as to what these documents can and cannot do). This system would allow policies for specific sites or types of development to be brought forward more swiftly than at present.

Supplementary plans would go through a process of independent examination which would be undertaken via written representations, though the Bill confirms that a hearing may be appropriate in certain circumstances.

The Bill also proposes that LPAs will be required to produce area-wide design codes; these supplementary plans would allow authorities to introduce design codes that set out the

“requirements with respect to design that relate to development, or development of a particular description”. In its

response to the Select Committee report on Planning Reform, the Government stated these will “

act as a framework for subsequent detailed design codes, prepared for specific areas or sites and led either by the local planning authority, neighbourhood planning groups or by developers as part of planning applications.”

The 2021 changes to the NPPF have already sought to encourage LPAs (as well as communities and developers) to produce design codes in their areas. Codes and other supplementary guidance are currently discretionary, and the pilot design codes being brought forward with support from the Office for Place predominantly focus on specific areas within an authority, such as urban extensions, neighbourhoods undergoing significant change, and strategic regeneration sites. Area-wide codes would represent a considerable step-change.

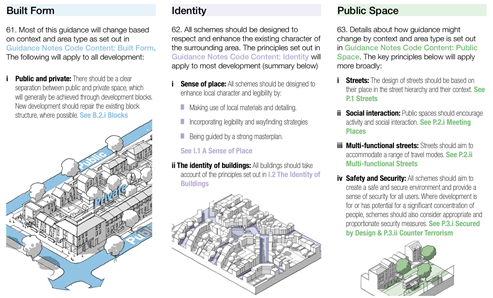

Design codes would be based on the existing framework set out in the

National Model Design Code (NMDC). This provides a template to support LPAs in producing their own codes, relating to area-wide guidance, alongside instructions for specific area/development types.

Figure 1. example of area-wide guidance in the NMDC. (P32)

Local authorities may wish to set more detailed area-specific parameters on matters such as building heights, density and materials, though these would likely be targeted at specific character areas rather than being authority-wide (e.g. high-rise, town centre, urban neighbourhoods, industrial areas, suburban).

The changes proposed would represent a definite shift in the range of work undertaken by many LPAs, and would likely require some in-house design capacity and expertise. Previous

research from Public Practice suggested that 80% of LPAs considered they did not have the in-house capacity or skills required to deliver the White Paper proposals, while the average estimated costs of preparing, consulting on and adopting a design code for an area of approximately 1ooo homes was found to be £138,636.

Where local authorities fail to produce area-wide codes, provisions in the Bill allow for the Secretary of State to intervene and direct the authority to comply with any required steps.

Neighbourhood Plans (and Street Votes?)

Neighbourhood Plans would be retained under the Bill, though amendments proposed to S38B of the PCPA provide further detail on the scope of what neighbourhood plans can include. This includes matters such as the level of affordable housing, infrastructure requirements, as well as the design and characteristics of development. The Bill would also seek to prevent neighbourhood plans from restricting housing related development, where this is proposed in a wider local development plan.

The Bill also proposes a new tool for neighbourhood planners, allowing groups to produce a ‘neighbourhood priorities statement’ (NPS). The Department has stated that this “is designed to be a more accessible, cheaper and faster way for communities to get involved in neighbourhood planning, particularly in areas that currently have low levels of take-up. NPSs will allow communities to identify key priorities and preferences for their area and may potentially act as a launchpad to preparing a full neighbourhood plan, design code or another community initiative. NPSs would also be used as a formal input to the local plan process with local authorities required to consider them”.

The most hyped element of the reform by the media was no doubt the new ‘

Street Vote’ provision

. This is intended to

“allow residents to propose development on their street and hold a vote to determine whether it should be given planning permission”, this would allow for the intensification of existing residential areas, with proponents suggesting this would be based on locally popular design. Given its fanfare, there is surprisingly little to say on this measure yet, with the explanatory note to the Bill stating that the clause is designed as a placeholder for a more substantive clause which may follow later. An existing

Streets Vote Bill had already been put before Parliament as a Private Members Bill, on the back of the Policy Exchange report

Strong Suburbs; both provide an idea of what is likely to come.

Initial thoughts

While the Government is yet to publish a formal response the White Paper consultation (it is imminent), it is clear that it has listened to its own backbenchers at least. Planning will continue to be presented as a local affair, and there is now greater expectation that decisions on new development will be plan-led. However, until the scope and nature of National Development Management Policies is known, the extent to which local plans are truly local, beyond site allocations, design codes and detailed area specific polies, will not be known either.

Plans will be simpler and shorter, with the process of producing them to be expedited. The proposals would also provide additional flexibility as to how new policies are brought forward, while also granting additional strategic powers where groups of LPAs consider this expedient. These are all commendable objectives that would go some way in making the system more user-friendly.

There are a lot of moving parts, however, particularly when other reforms such as the infrastructure levy and the devolution provisions are added to the mix. Previous experience of planning reform has shown there is a real risk of inertia as LPAs and other parties get to grips with the changes. Hopefully a better funded system (through the proposed increase in planning application fees) may assuage this but, by itself, that is unlikely to be enough for LPAs to resource the suite of changes required.

Further, many will rightly question whether the changes have let some authorities off the hook, enabling them to avoid the difficult decision of allocating sufficient land to meet local needs. You will hear little on housing numbers in any recent statements from Gove, and perhaps this is part of the Government’s strategy.

In any event, the changes are probably more than a year away. The Bill will first need to make its passage through Parliament before being enacted – the Government is targeting Royal Assent by the year end or early next. Many of the provisions will also require changes to national policy and additional regulations brought forward via secondary legislation, as such there is still time for things to change considerably.

[1] As referred to at para 50 of the Explanatory Notes to the Bill

HM Government, Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill, Further Information policy paper