Following changes that came into force on 1 September, this blog reflects on our experience working with Class E six weeks on.

As reported in our

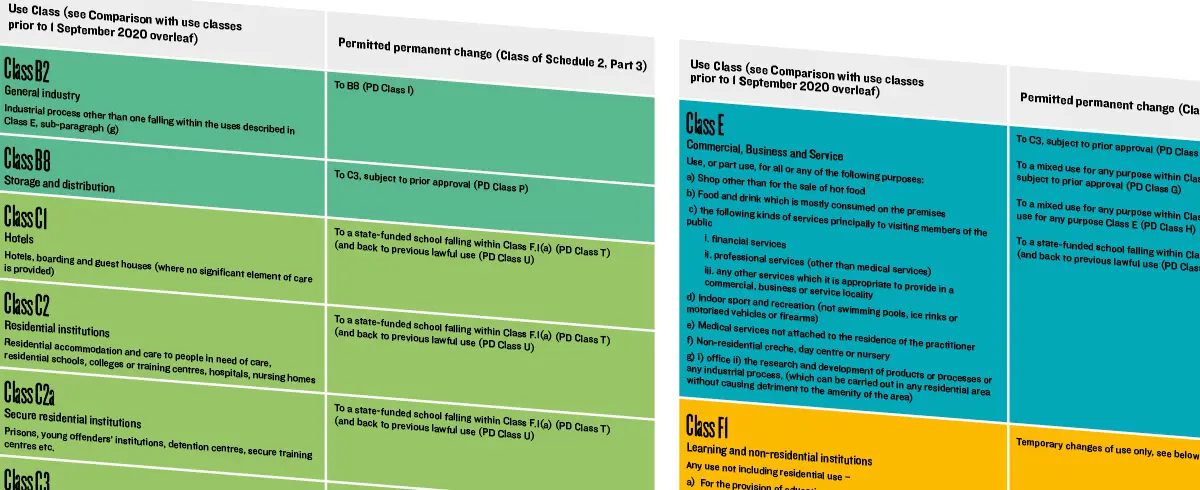

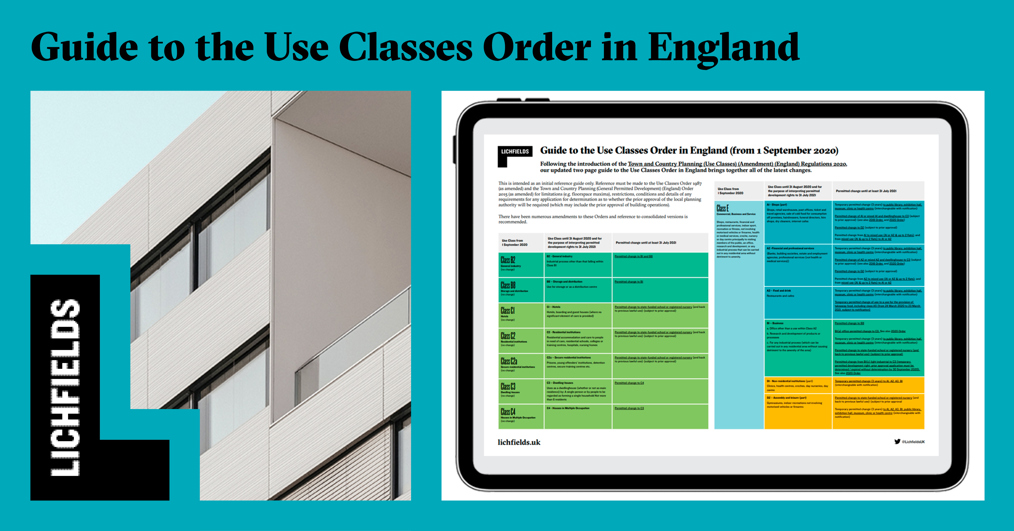

blog at the time of the Government’s announcements, these changes represent the most fundamental change in town centre planning for over 30 years. Combining Use Class A1, A2, A3, B1 and parts of D2 into a new Class E. Creating a new F.1 and F.2 encompassing education and community type uses and making more uses Sui Generis (including pubs) introduces both new flexibilities and restrictions.

So far, the new flexibilities seem to have been broadly welcomed, but there are already some unforeseen consequences emerging to be mindful of.

The need for an overhaul

Those working in town centre development had recognised for a long time that the Use Class Order (1987, as amended) was outdated, inflexible and needed to change. The planning system simply could not keep pace with changing trends and operators.

Operators have struggled to fit neatly into use classes. The Use Classes Order did not account for blurred boundaries with a range and mix of uses within units. Coffee and bakery shops, had the potential to be A1, A3 or A5, depending on factors like the amount of seating, the proportion of takeaway sales and whether food is cooked or reheated on the premises. This lead operators to apply for a combination of A1, A3 and/or A5 use.

Image credit: @1ookmumnohands

The rigid approach to categorisation also failed to keep up with the diverse mix of uses emerging within single units. For example, cycle shops blending workshop, bar, café and events space; or yoga classes and cookery classes taking place within a retail store. Whilst the high street was trying to respond to shifting consumer demands, the creaking system was deterring experiential and enrichening uses aimed at drawing customers in to centres and creating vibrancy throughout the day and into the evening.

A more fluid and simplified approach to the categorisation of town centre uses was clearly needed.

Unprecedented deregulation

Previous

consultation by Government in 2018 discussed merging A1-A3 uses to support the high street. However, few foresaw that these changes would be introduced so quickly, and especially not taking an even bolder encompassing of B1 and parts of D2.

The Government seems to have been spurred on by coronavirus which has brought matters to a head earlier than anticipated.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

This is particularly important at the present time as town centres seek to recover from the economic impact of Coronavirus. Modern high streets and town centres have changed so that they now seek to provide a wider range of facilities and services, including new emerging uses, that will attract people and make these areas viable now and in the future.

Explanatory Memorandum to The Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2020 No. 757 1 |

|

| |

|

|

There was already the option to change between some town centre uses on a temporary basis,

introduced in May 2019, subject to conditions and limitations and in some cases prior approval, but the changes introduced really did go well beyond what we have seen before.

The radical nature of the changes possibly accounts for why so many are watching with interest for the outcome of the court challenge by Rights : Community : Action (RCA). The grounds of challenge included failure to properly consult before making the rules. Could the changes be quashed this month?

A change for the better?

Local authorities and developers alike are still getting to grips with the new flexibilities. Here are some of the examples we’ve experienced to date:

Is my business in Class E?

Article 7 of the 2020 Order, in terms of transitional arrangements, confirms that if premises were in use Class A1, A2, A3 or B1 of the time of the previous Order on 31 August 2020, the building or land is to be treated, after the 1 September 2020, as being used for the purpose specified in Class E as on 31st August 2020.

Updated Article 3 1(a) of the Use Class Order (as amended) importantly now states with regards to Class E (and F.1 and F.2) that the use of that building or that other land, or if specified, the use of part of that building or the other land ("part use"), for any other purpose of the same class is not to be taken to involve development of the land.

The changes however do not override planning conditions and legal agreements – so these still need to be checked and taken into account in terms of restrictions on use. This may mean premises do not benefit from Class E and its flexibilities.

In addition, for recently completed builds, if the unit has not yet been brought into use as permitted it would again not benefit from the flexibilities. Presumably the Government’s intention was to focus on bringing life back to older units in high streets - however this seems a notable flaw.

There also remains a degree of debate about whether a use falls within Class E. For example, is a gastropub (arguably A3/A4) to be considered within Class E? The new Order specifies that “drinking establishments with expended food provision” are Sui Generis. A gastropub could arguably be considered as A3 if it is more dining oriented rather than drinking. But where does one draw the line?

This distinction may be important for owners seeking to secure flexibility within Class E but others may require certainty for valuation or rating purposes. Certificates of lawful use may be increasingly be used to provide clarity and assurance in this regard.

How does one assess proposals for Class E?

Assessing an application for Class E, which would previously have been a single more tightly defined use is now potentially mixed use. Assessing the impacts of some development (economic and transport) will be more problematic. Local authorities are likely to consider the worst-case parameters or consider imposing restrictive conditions. Whilst Class E provides flexibility, applicants need to be mindful of the potential implications of this approach and may choose to self-impose limitations at the application stage in order to avoid extensive mitigation.

Should the planning application apply for Class E or a sub-category or activity?

In order to avoid assessing a range of impact scenarios, applicants may choose to apply for sub-categories or activities within Class E, in the same way applications refer to food stores or bulky goods retail warehouses within the old Class A1. This could be done without directly referring to the sub-category, albeit it would be referred to in a condition controlling the operation of the Use Classes Order. This approach could minimise the amount of supporting evidence and assist the planning authority’s consideration of the planning application.

How will the UCO changes affect the evidence base and plan making more generally?

Traditionally evidence bases studies such as employment land and town centre/retail studies have focused on floorspace capacity projections adopting the old use classes. The creation of Class E and other changes has blurred the lines and there are significant overlaps. This is likely to lead to confusion and planning authorities will need to revisit their evidence base. Nevertheless, the need for sub-categories of use within Class E will be required. A global floorspace projection for Class E is unlikely to be appropriate or provide sufficient detail for plan making purposes. We are already seeing local authorities at early stages of plan making consider how they might control Class E flexibilities in their Primary Shopping Areas.

For those already at advanced stages of plan making, changes to reflect the updated use class have had to be taken on board. For example, Brent in its

Proposed Modifications to its Local Plan now refers to uses i.e. comparison retail, restaurant, takeaway rather than use classes.

How can planning conditions be used to control development?

To address the issues outlined above, we envisage planning authorities and applicants will make greater use of planning conditions to control the type of development that is implemented. This approach is not new, for many years Class A1 retail has been restrict via conditions in relation to the type of goods that can be sold. In the same way conditions restricting potentially harmful activities within Class E are likely to be applied.

How has PINS responded?

In Richmondshire (appeal ref: APP/ V2723/W/20/3247987) a change of use for a florist to a café considered in conflict with the development plan (due to loss of retail) the Inspector afforded “considerable weight” to the Use Classes Order and deemed to be “a significant fallback position”. Although it is still early days, this decision may be indicative of the direction of travel.

Lichfields will be continuing to monitor the changes carefully and will provide further commentary as more experience is gained. If you would like to discuss any aspects of the recent changes of the Use Classes Order, please do

get in contact.