Without a doubt, the UK housing crisis is most acute in the capital. Not a day goes by without a story on prices, the need for housing, or how to / where to / why to build more homes in London. Most recently, an old, controversial topic was re-introduced – building homes on the Green Belt.

The context for this debate is crucially important - there is no one, single solution. But understanding the context within which the Green Belt debate sits is vital to building homes.

So, here are six key London housing issues to remember.

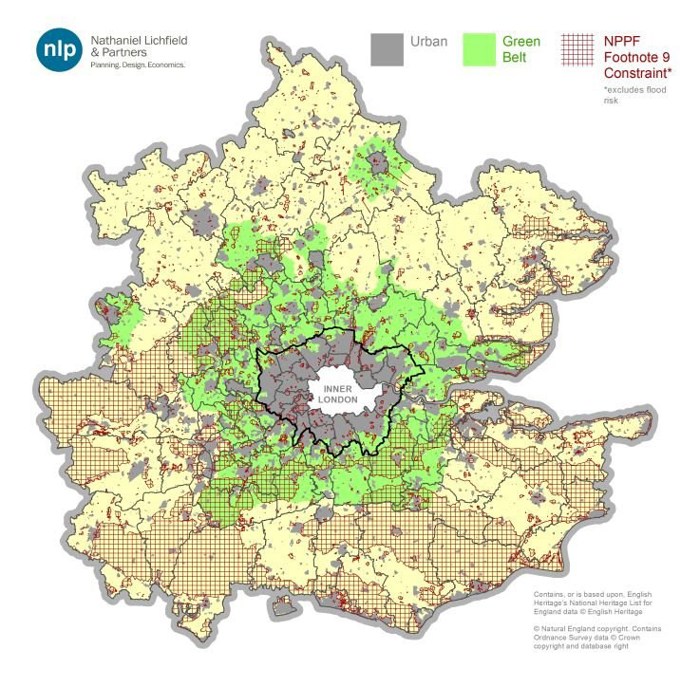

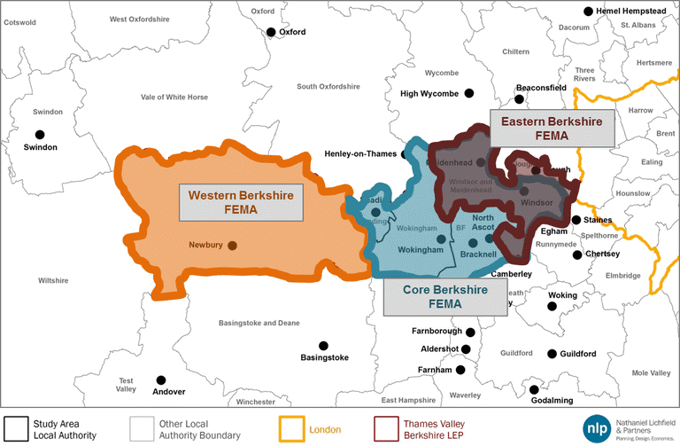

- The Green Belt is a significant area of land around London but there are other constraints on development too.

In outer London boroughs, 28% of land is Green Belt (which is a planning designation designed to prevent towns from expanding, not a landscape or ecological one), reaching as high as 54% in one borough. However, beyond the Green Belt 34% of land is covered by other constraints that national planning policy says may also restrict development, such as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and National Parks.

Figure 1: London, Green Belt and footnote 9 constraints | Source: NLP Analysis

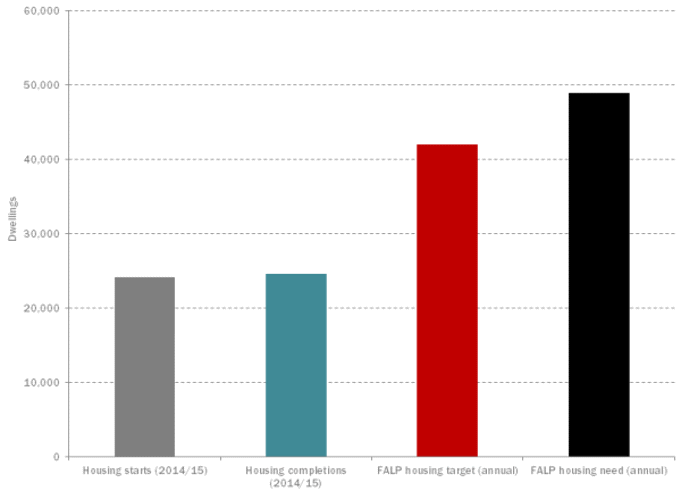

- Demand for homes inside London is high but supply is falling well short.

The Mayor’s most recent iteration of his London Plan set out a need for between 49,000 and 62,000 homes per year, but the planning inspector who scrutinised it, said current policies meant London would not be able to meet this need, and set a more realistic annual target of 42,000 homes. In 2015, just 25,000 homes were built, and although output is expected to grow for 2016, it will be below what’s required. If need is not able to be met in the capital it will ‘overspill’ to neighbouring areas.

Figure 2: Housing starts, completions, target and need in London | Source: DCLG; FALP; NLP analysis

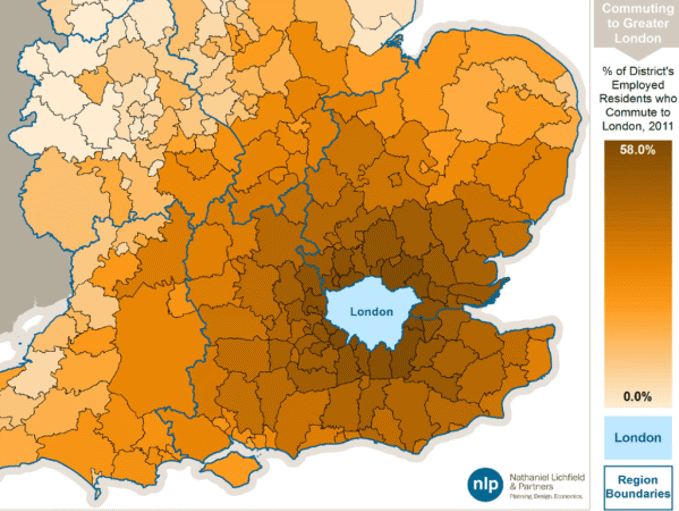

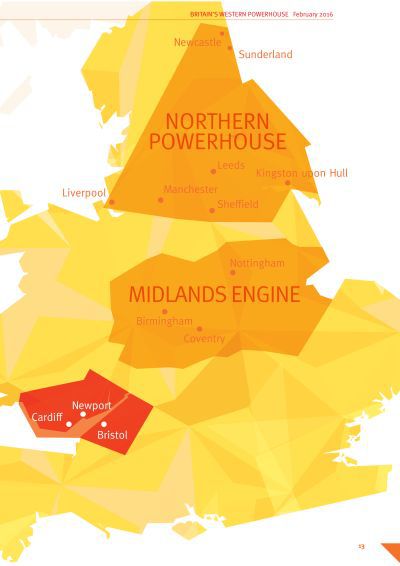

- London’s housing market influence reaches far beyond its outer boundary.

Because London is a magnet for people wanting to live and work here, household growth continues apace. London’s overspill needs puts pressure on surrounding areas in the commuter belt, but many of these places have their own housing needs which many already struggle to meet, due to Green Belt and other constraints. This raises prospect of the double overspill – pushing housing to locations even further out from London, with longer and more expensive commutes for many.

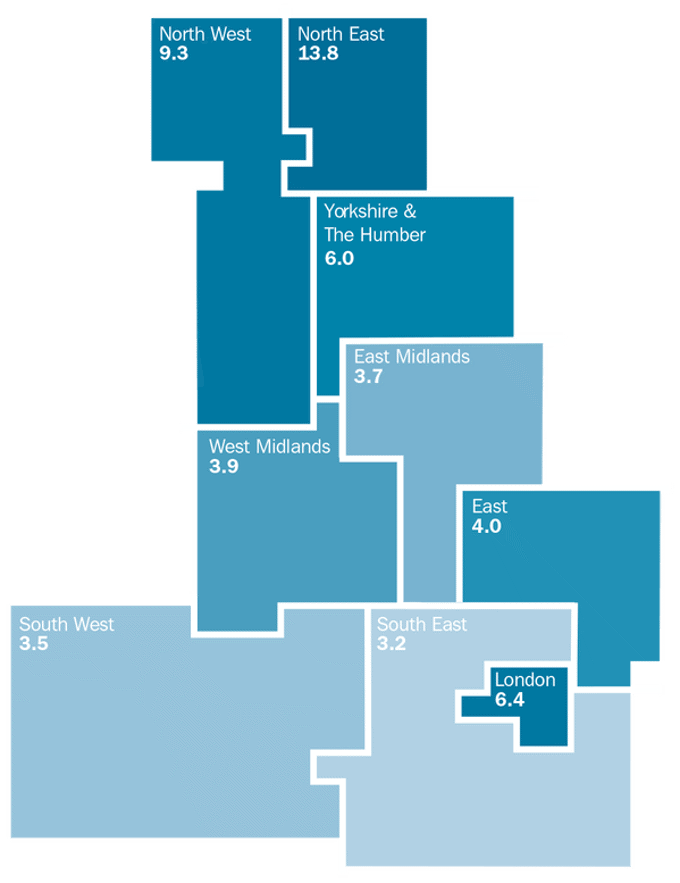

Figure 3: Proportion of district’s employed residents that commute to London | Source: ONS; NLP analysis

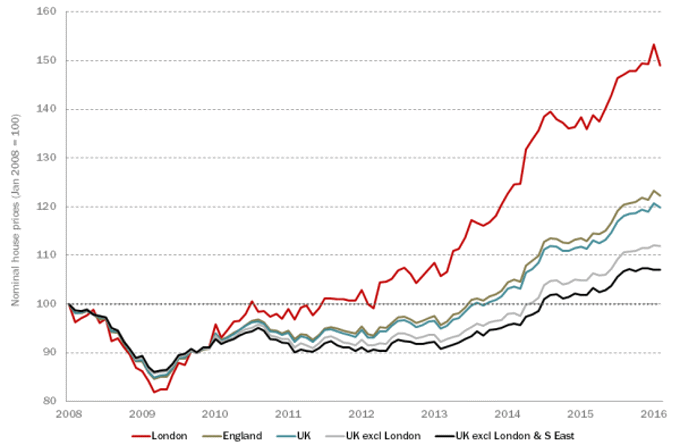

- Housing undersupply means London house prices are extremely high.

House prices in London are now almost 50% higher (in nominal terms) than the pre-crash peak – prices in the UK excluding London are only 12% higher.

Figure 4: Nominal house prices since the pre-crash peak | Source: ONS; NLP analysis

- Brownfield land isn’t a panacea.

While it is important to consider all types of land for development, brownfield land often has viability and remediation difficulties before houses can be built. It is not always in locations where people are willing to live, and is often currently used to accommodate London’s industries, who would need to be relocated. And, it won’t last forever: in London, even if we only used brownfield land to fully meet the capital’s annual housing need, we would run out completely in six years.

Figure 5: The number of years suitable brownfield land for housing would last if only this land met annual need | Source: NLUD-PDL; NLP analysis

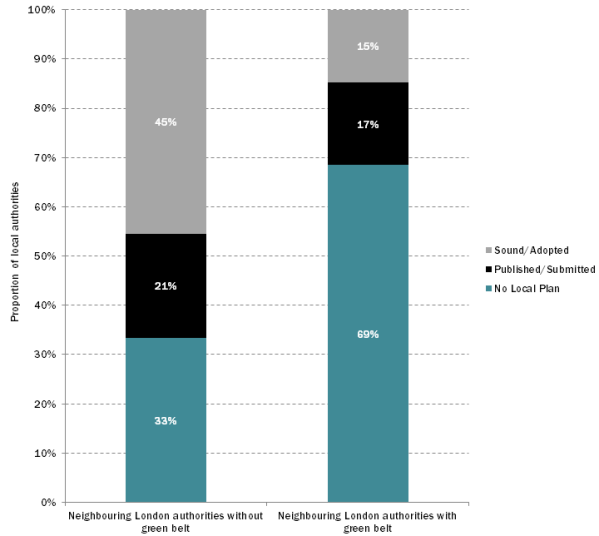

- Local plans progress can be slow.

The Government wants local councils to prepare Local Plans to ensure that land is identified for housing to meet needs. But progress is slow. Nationally, just a third of Local Authorities have an up-to-date Local Plan, and for those Green Belt areas surrounding London, the figure is a derisory 15%. The Government has said it expects Councils to produce new Plans by “early 2017” or risk intervention and is considering further reforms. No-one yet knows how this will play out, but until Plans are in place, London and its hinterland will fail to plan effectively for the homes that are needed.

Figure 6: Local plan progress in areas surrounding London | Source: PINS; NLP analysis

No-one yet knows how this will play out, but until plans are in place, London and its hinterland will fail to plan effectively for the homes that are needed.