All the speakers established that new river crossings are required to support the current population growth in London. However, what stood out to me was that whilst TfL is considering the imminent ‘need’, has published a “River Crossings Plan” and undertaken long-term work with many stakeholders and expert groups, there was no consensus on the locations or form of said proposed crossings.

It is increasingly recognised that meeting infrastructure needs is vital to delivering housing, particularly as London’s population is due to increase to circa 11 million people by 2050. The Barking Riverside planning permission for 10,800 homes is a prime example of how proposed river crossings can release otherwise unviable brownfield land in Greater London for housing - the housing figure for this development is partially based on the London OvergroundeExtension to Thamesmead. Without significant transport improvements, the original masterplan permission in 2007 imposed planning conditions on the site to limit development to only 1,500 units.

Existing observed trips in London are higher than forecast in the latest Mayor’s Infrastructure Plan and transport capacity is becoming an increasing concern. As a starting point, there are a number of initiatives to increase capacityand shift transport mode within existing TfL assets, such as the new superhighway on Vauxhall Bridge.

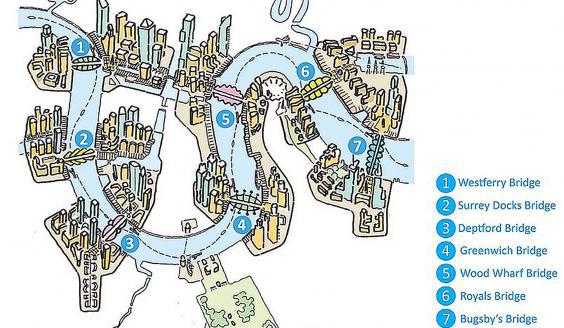

TfL’s Plan “Connecting the Capital” identifies thirteen new locations for river crossings, some of which are in place, while others are long term visions. These crossings fall into four categories, pedestrian/cycleways, passenger ferry opportunities, public transport crossings and highways all in the form of bridges, tunnels or boats:

- Jubilee Line (public transport)

- Crossrail 2 (public transport)

- Nine Elms to Pimlico (footway/cycleway)

- Garden Bridge (footway/cycleway)

- Rotherhithe to Canary Wharf (footway/cycleway/passenger ferry)

- North Greenwich to Isle of Dogs (passenger ferry)

- Silvertown Tunnel (highway)

- Charlton (passenger ferry)

- Crossrail (Public transport)

- Gallions Reach (highway)

- Barking Riverside to Thamesmead (public transport)

- Belvedere (highway)

- Lower Thames Crossing (highway) although this is outside of the Greater London area)

It was clear that there is an interesting conundrum – balancing north/ south accessibility and connectivity, with maintaining theeast/ west route along the river. It must also be considered that, if a bridge is required to be ‘raised’ too often for shipping to pass, then it is not creating a north-south connection as required by the general population. Unfortunately, the tide has no respect for rush hour and ships are bound by tidal movements. I’m confident that accessibility in all four compass directions is not an insurmountable problem but it was brushed over somewhat by speakers. Further concerns were voiced from the floor in relation to ‘too many proposals for highways’ when the national planning policy and government agenda clearly promote sustainability and use of public transport - another issue that was not discussed in depth.

Perhaps more radical thinking is required, such as that suggested by one audience member – a ‘Thames Barrage’ - producing a large freshwater lake. Although this may be easier for river transport and north-south connectivity, the Environment Agency may have some concerns! Perhaps we should learn from best practice, in cities such as Rotterdam. So many options to consider….there is no doubt that this issue will move higher and to the forefront of the Government’s London transport agenda in coming months and years.