In January 2021, the Minister of State for Housing, the Rt Hon Chris Pincher MP, set out clear guidance that local planning authorities [LPAs] should continue plan-making despite the challenges presented in 2020/21 by Covid-19 and pending policy changes signalled by the Planning for the Future [PftF] White Paper. In his Written Ministerial Statement, Pincher once again impressed upon LPAs the importance of ensuring Local Plans are up to date, stating that they are critical to “help ensure that the economy can rebound strongly from the COVID-19 pandemic. Completing Local Plans will help to ensure that we can build back better and continue to deliver the homes that are needed across England.”

As many planning professionals will be well aware, the West Midlands has been struggling (unsuccessfully) with the significant strategic challenge of meeting the unmet housing needs of Birmingham for a number of years. Many authorities within the Greater Birmingham and Black Country Housing Market Area [GBBCHMA]

[1] have been undertaking Local Plan Reviews to grapple with how they can best assist Birmingham in addressing its stated housing shortfall of c.37,900 dwellings by January 2020, as was established in the adopted Birmingham Development Plan [BDP] (2011-2031).

However, like many of Lichfields’ clients across the West Midlands, I have spent the last few years watching, exasperated, the glacial pace of plan-making within the region. This is not just about numbers in a theoretical Position Statement – this is affecting countless real households who cannot access the housing needed because simply not enough homes are being built in this sub-region.

In the last few months, we have seen a resurgence in plan-making in this part of the West Midlands, with several Regulation 18 consultations and Local Plan submissions to the Secretary of State. And finally, the Inspector’s Report for the North Warwickshire’s Local Plan, originally submitted under the National Planning Policy Framework’s [NPPF] transitional arrangements way back in March 2018, has been published.

[2] Interestingly, and building on Simon Ricketts’ unusual planning metaphor

[3], this would have allowed sufficient time for the birth of at least two elephants, or three camels. Even so this recent uptick in plan-making can do little to cover up the fact that the region has been plagued by housing shortages for years, and is still failing to plan for these needs either strategically or promptly.

The publication of the Draft Black Country Plan in July 2021 (in advance of its formal consultation

[4]) has once again brought this issue to the fore. The emerging plan has identified an extremely high housing shortfall in the order of 28,000 dwellings up to 2039 across the Black Country. This is

on top of the existing shortfall in Birmingham up to 2031, which the other districts were already struggling to meet. The inability of the main urban centres of the GBBCHMA to meet their minimum housing needs is therefore a recurrent strategic planning issue, which is unlikely to resolve itself without significant bold intervention.

Birmingham City Council [BCC] remains steadfast that there was no need for the Council to review its BDP, as the GBBCHMA authorities had made

“significant progress” towards meeting Birmingham’s unmet needs

[5]. Indeed, the July 2020 Position Statement concluded that the unmet need was now ‘just’ 2,597 dwellings to 2031. However, having reviewed the outcomes from the recent spate of plan-making activity across the GBBCHMA, I think it is pretty clear that that this is not the case. Indeed, several of the assumptions underpinning BCC’s position on supply have not actually materialised. Having reviewed each Council’s stated housing contributions, my view is that the acute level of unmet housing need up to 2031 will not be addressed, even before we factor in the emerging needs of the Black Country up to 2039.

Birmingham’s unmet housing need saga

1. How much?

Given the complexity of the debate, it is perhaps worthwhile to first set out how Birmingham’s unmet housing need has evolved.

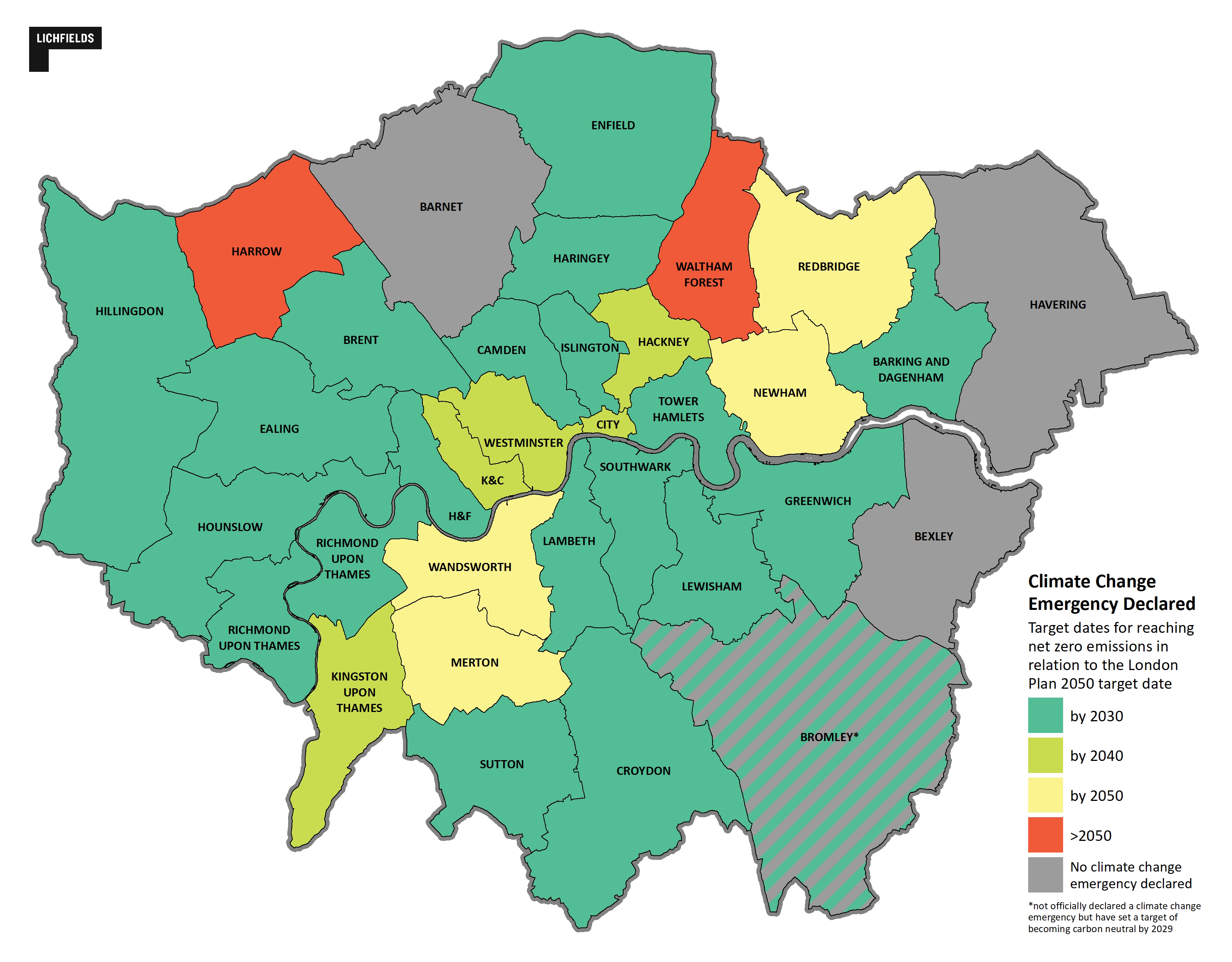

BCC’s position has primarily been set out within the ‘2018 Strategic Growth Study’ (‘the 2018 SGS’), The ‘Housing Need and Housing Land Supply Position Statement’ (September 2018) (‘the 2018 Update’) and most recently the ‘Greater Birmingham and Black Country Housing Market Area (GBBCHMA) Housing Need and Housing Land Supply Position Statement’ (July 2020) (’the 2020 Position Statement’). A summary of the concluded shortfall is shown below. The chart compares how the original 37,900 unmet need identified in the original BDP has been gradually whittled down by successive supply reviews, driven by BCC.

Figure 1 Comparison of GBBCHMA Unmet Housing Need Positions

Source: Lichfields’ analysis, based on GBBCHMA Position Statements

Each of these positions has featured very different land supply positions, generally reflecting either changing supply evidence or differing assumptions on densities.

[6] Indeed, the latest position reflected BCC’s ‘

Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) 2019’ data, which concluded that completions over 2011 to 2019 had exceeded the requirement by c.1,374 dwellings and that the Council’s supply of land has increased by c.14,300. It would be interesting to explore whether

all of the 14,300 additional dwellings identified are developable.

Setting that to one side, this seems to indicate a downward trend in Birmingham’s unmet need, even though no Local Plan has passed examination which has formally committed to meeting Birmingham’s unmet need. Taking the 2020 Position Statement at face value suggests that this significant unmet need challenge has been met. However, the raft of position statements above all use an unmet housing need figure derived for the whole GBBCHMA (i.e. Birmingham and the Black Country) which has not been tested through the examination process.

So, what is the unmet housing need figure GBBCHMA authorities should be addressing? Arguably, the only adopted – and examined – shortfall is that which has been set out in the BDP. Therefore, the actual figure BCC ought to be considering the contributions against remains the adopted 37,900 shortfall.

2. How much is not enough?

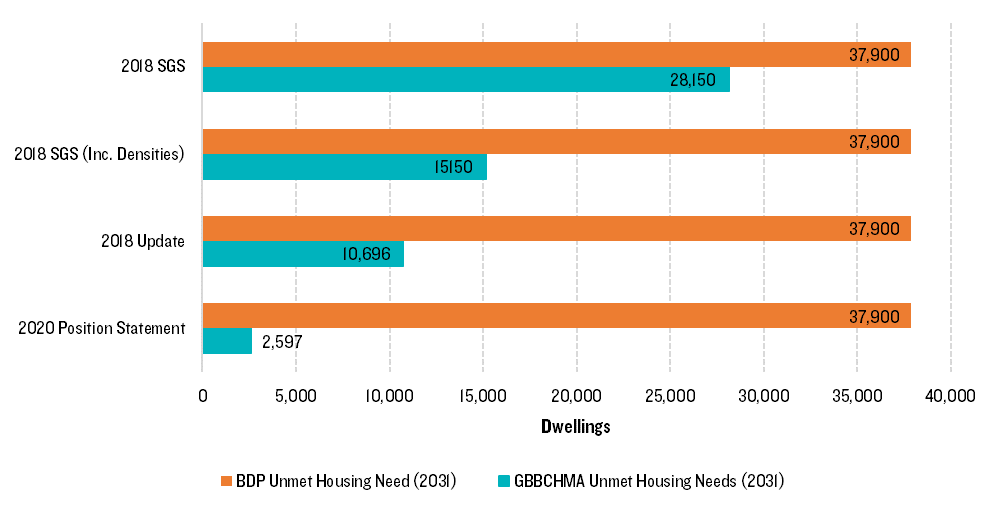

So, are the GBBCHMA authorities meeting this 37,900 need? Appendix 2 of the 2020 Position Statement sets out the allocated and emerging contributions made by the GBBCHMA authorities, which it says totals between 18,130-20,130 dwellings:

Figure 2 Summary of Direct Contributions to GBBCHMA’s housing shortfall

Source: Lichfields based on Appendix 2, 2020 Position Statement

This position is now over a year old, and the debate has moved on; furthermore, there are critical flaws in the assumptions underpinning the direct contributions summarised above. Firstly, BCC has ‘banked’

all of the commitments for the whole of the GBBCHMA, including any commitments for other GBBCHMA authorities. This is now particularly pertinent given the Black Country’s emerging unmet housing need of 28,239 homes up to 2039.

[7] Secondly, several of the contributions are now markedly less than stated. Looking at these points by district:

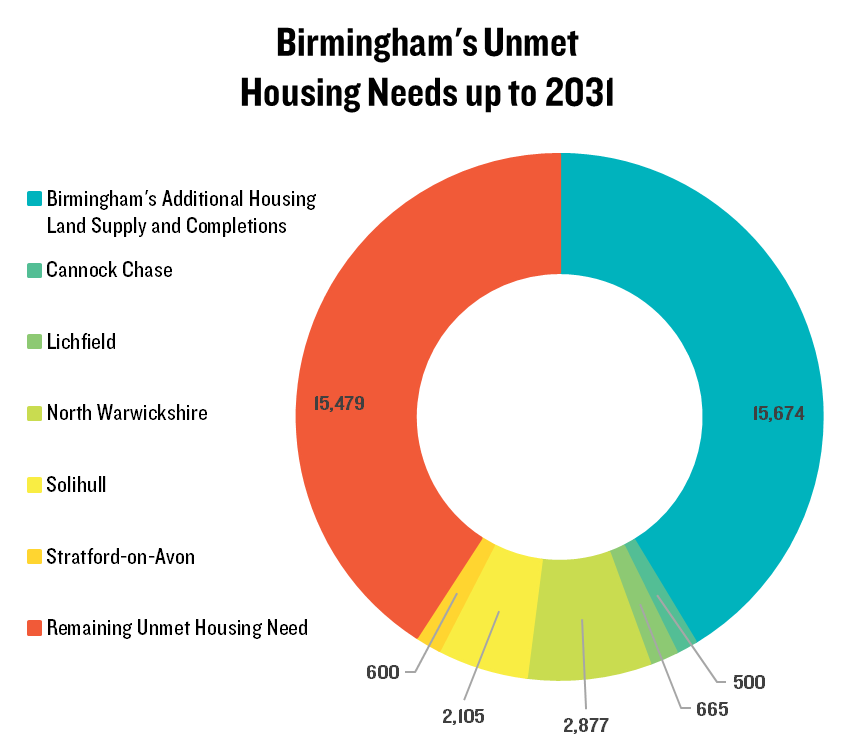

- South Staffordshire – ‘Up to 4,000’: It is not clear how much of South Staffordshire District’s emerging c.4,000 dwelling contribution can realistically be said to be exclusively Birmingham’s, given that even the most cursory glance at a map shows that the District wraps around Wolverhampton, Stourbridge and to a lesser extent Walsall. It will obviously have a major role in meeting the Black Country’s emerging unmet needs up to 2039. Furthermore, there are no signed Statements of Common Ground [SoCG] or Memorandums of Understanding [MoU] agreeing to this contribution for Birmingham. At best, only a small part of this 4,000 contribution is likely to be meeting Birmingham’s unmet needs, with the bulk going towards the Black Country’s;[8]

- Lichfield – ‘4,500’: In the Lichfield District Local Plan 2040 Regulation 19 consultation, Lichfield City Council has already reduced its contribution from c.4,500 to c.2,665. Moreover, the Council is apportioning 75% of this contribution to help meet the Black Country’s emerging unmet housing need, reducing its contribution to Birmingham from 4,500 to 665 (paragraph 4.22);

- North Warwickshire – ‘3,790 + 620’: The North Warwickshire Local Plan has now passed its examination. The Examining Inspector’s Report notes that the Memoranda of Understanding between “NWBC and BCC and TBC acknowledge that the ‘discrete’ figure of 913 homes is subsumed within the overarching figure of 3,790” (IR127). In essence, only 2,877 dwellings are actually going towards meeting Birmingham’s unmet housing needs; and

- Stratford on Avon – ‘2,720’: The 2020 Position Statement states that this c.2,720 dwelling contribution arises from the Coventry and Warwickshire MoU, which estimated that c.50% of the Council’s c.5,440 dwellings, above its demographic need, could be apportioned 50/50 between the GBBCHMA and Coventry and Warwickshire HMA. However, this is completely at odds with the Inspector’s conclusions at the Core Strategy Examination and the purpose of Policy CS.16, which is to provide a mechanism to meet these needs. Indeed, the Inspector was clear that the “MoU has identified a figure but this is based on an incorrect assumption that everything over and above the demographic need is ‘surplus’ and available to meet the needs of others.” (IR62). In essence, only the 600 dwellings being brought forward through the emerging Site Allocations Plan would contribute towards Birmingham.

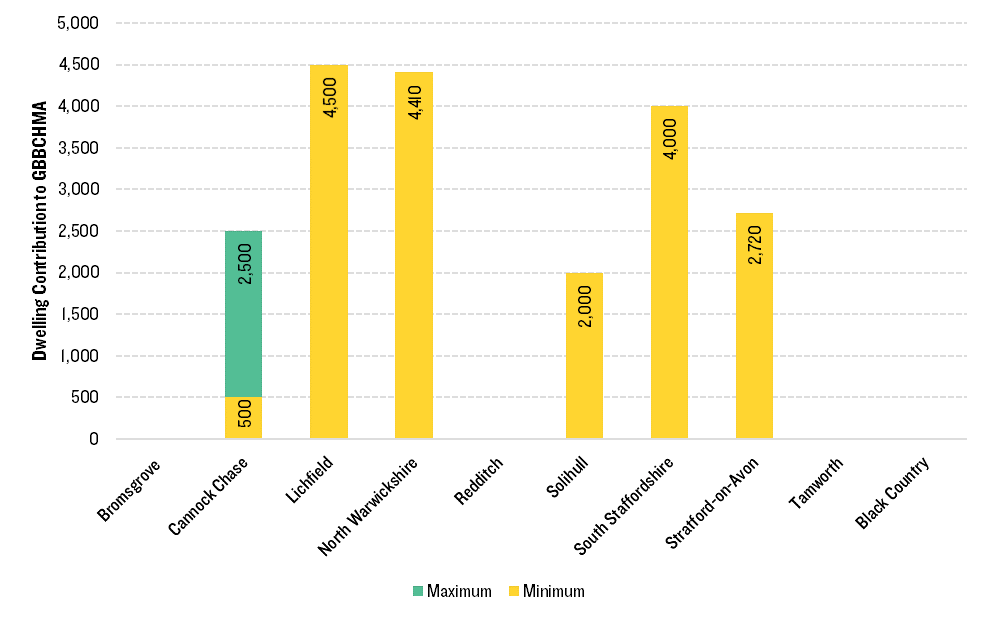

Taking all of this into account, whilst Birmingham’s unmet housing need has probably reduced from the original 37,900 in 2017, there remains a likely – and at present, unaccounted – shortfall of between

c.11,479-15,479 dwellings up to 2031.

[9] This is because several of the ‘banked’ housing contributions from other HMA districts are earmarked to help meet the Black Country’s needs.

A call to (regional) arms

Despite several years of plan-making, and ‘evidence’ suggesting it had, ultimately, it is clear that Birmingham’s unmet housing needs have not been fully addressed within the GBBCHMA, with between c.11,500 and 15,500 remaining up to 2031. With several authorities unable to help meet these needs, and several others already committed elsewhere, it is clear that GBBCHMA’s current approach to plan-making and strategically addressing these needs through the Duty to Cooperate is not working. At present, it is unclear as to how these needs will be addressed.

This is, of course, only one part of the problem. There is an emerging c.28,000 shortfall up to 2039 elsewhere in the HMA, in the Black Country. Further still, beyond 2031, there is likely to be a very considerable level of additional unmet housing need arising in Birmingham as a result of the City being subject to the Government’s 35% urban uplift

[10] on its local housing need figure, whilst the LHN figure will rise still further when the standard method Local Plan ‘cap’ is removed in January 2022.

[11]There is no single panacea to determine the proportion of unmet needs that LPAs should seek to accommodate from others. However, that is not an excuse to ignore the issue and the West Midlands urgently needs to grapple with this before the level of need spirals ever further out of reach (see for example, London and the Greater South East). My view is that a formal mechanism needs to be agreed to ensure that the LPAs in the HMA are compelled to work together to meet the unmet housing needs of

both Birmingham and the Black Country promptly. It needs an evidenced-based approach to distributing these needs amongst the authorities, perhaps one that is similar to the functional relationship approach taken by North Warwickshire

[12], to ensure that this need is distributed sustainably. But, at the very least, and as Zack Simons has said,

[13] we need to talk about the Green Belt. A regional review is long overdue. Whilst the need to regenerate brownfield sites is an important part of the mix, the release of large-scale Green Belt sites in sustainable locations, whilst politically difficult, is a logical (and sensible) approach to comprehensively addressing this critical issue.

Until then, all the west is laying plans, but in the meantime meeting unmet housing needs has gone awry..

[1] Comprising the seven Greater Birmingham districts, the four Black Country districts, South Staffordshire, North Warwickshire and Stratford-on-Avon (The latter two also fall within the Coventry-Warwickshire Housing Market Area). It can also be further refined into two sub markets: the Birmingham sub-market and Black Country sub-market.[2] Published 20th July 2021[3] Simoncity - Gestation Of An Elephant: Plan Making. Available at: https://simonicity.com/tag/local-plan-examination-soundness/[4] The formal consultation will start on the 16th August and run for eight weeks to 11th October 2021[5] Birmingham City Council (2020): Annual Monitoring Review 2020, page 3[6] The 2017 land supply data in the 2018 Update suggested that the land supply had increased by 5,629 since the 2018 SGS. However, the land supply figures are not quite directly comparable, as the 2018 Update removes the 5%-15% non-implementation discounts on supply. Furthermore, it does not apply the 13,000 additional dwellings resulting from the increased densities.[7] Para 3.21, The Draft Black Country Plan (July 2021)[8] A letter (dated December 2019) from the Association of Black Country Authorities requests that the whole contribution is made towards the Black County’s unmet needs, rather than Birmingham’s.[9] Dependent on how much of South Staffordshire’s 4,000 dwelling contribution can be attributed towards Birmingham.[10] Both Birmingham and Wolverhampton and subject to the 35% urban centres uplift, following the Government’s changes to the standard method in December 2020 as set out in the Planning Practice Guidance.[11] PPG ID: 2a-004: “Where the relevant strategic policies for housing were adopted more than 5 years ago (at the point of making the calculation), the local housing need figure is capped at 40% above whichever is the higher of: a. the projected household growth for the area over the 10 year period identified in step 1; or

1. the average annual housing requirement figure set out in the most recently adopted strategic policies (if a figure exists).”

[12] North Warwickshire’s Local Plan considered the proximity, connectivity and strength of functional inter-relationships with neighbouring areas (IR121), using the 2011 Census data relating to commuting trips between Birmingham and North Warwickshire to establish the scale of its contribution. This evidence-based approach was endorsed by the Inspector (IR127).[13] We need to talk about England’s Green Belt (Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/f240e825-eca0-4fba-8813-86dfaa0a6933)