The provision of safe, stimulating and inclusive play space is a critical planning issue that can often be the making of or… breaking of… a successful planning application. When done right, play can help support children and young people’s development and mental and physical health, as well as delivering high quality placemaking that benefits all ages.

In London (home to over 2 million residents under the age of 18

[1]), play space needs to be delivered within the limitations of spatially constrained sites, requiring design imagination and a careful balance with other space demanding design and policy requirements within a scheme. When it comes to play space provision in the capital, quality is as important as quantity.

At a strategic level, the policy requirements for play are set out within Policy S4 (Play and informal recreation) of

the London Plan (2021) and the somewhat dated

[2],

Shaping Neighbourhoods: Play and Informal Recreation SPG (September 2012). At a local level, more detailed policy criteria is provided within Local Plans or SPDs.

Given that 2023 marks the 2-year anniversary of the London Plan, and in anticipation of a new London Planning Guidance (‘LPG’) document

[3] on play space to supersede the 2012 SPG

[4], we reflect below on the key planning issues that are commonplace with the delivery of play space for London’s development and provide our insight on best practice and lessons learnt.

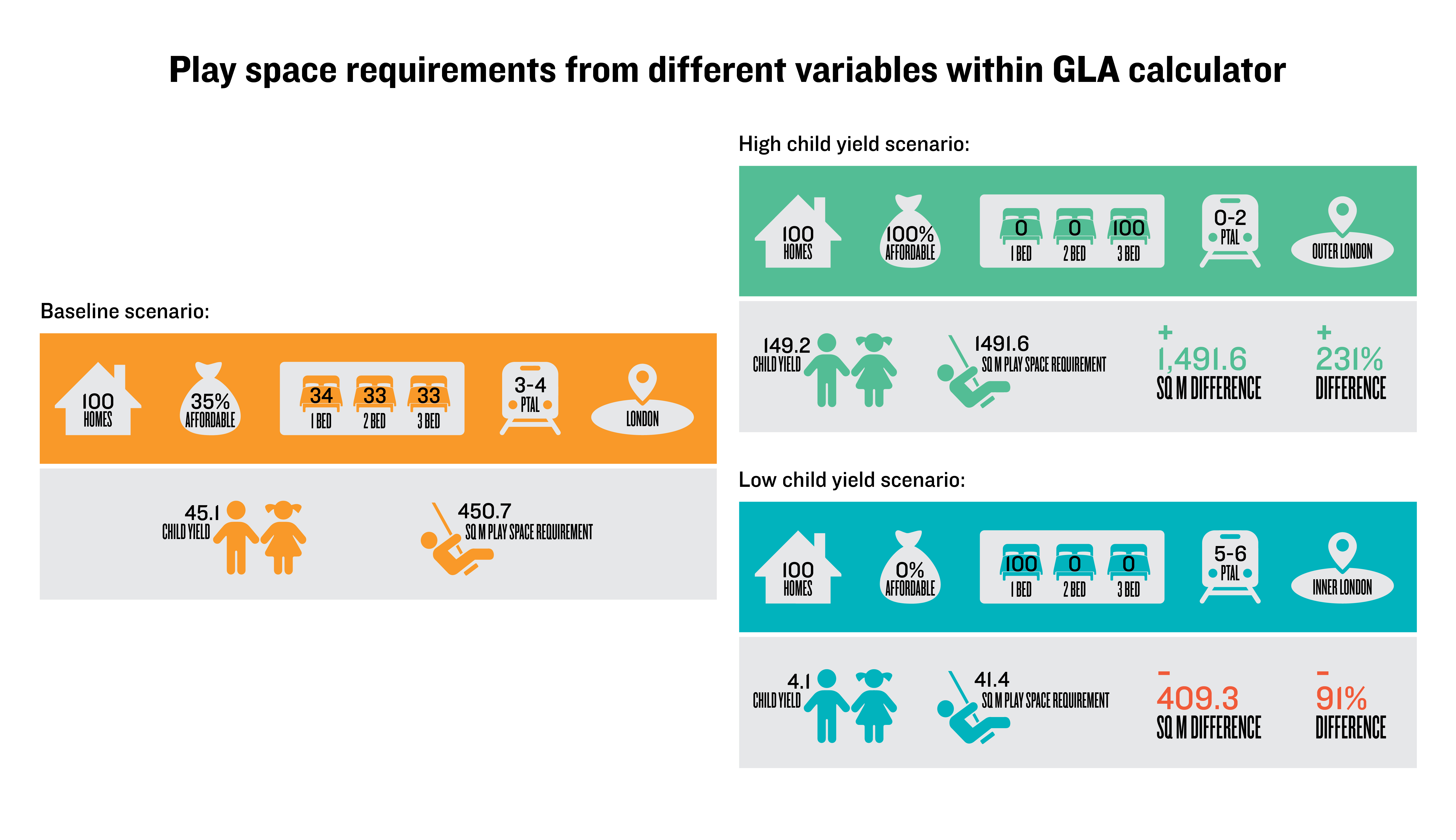

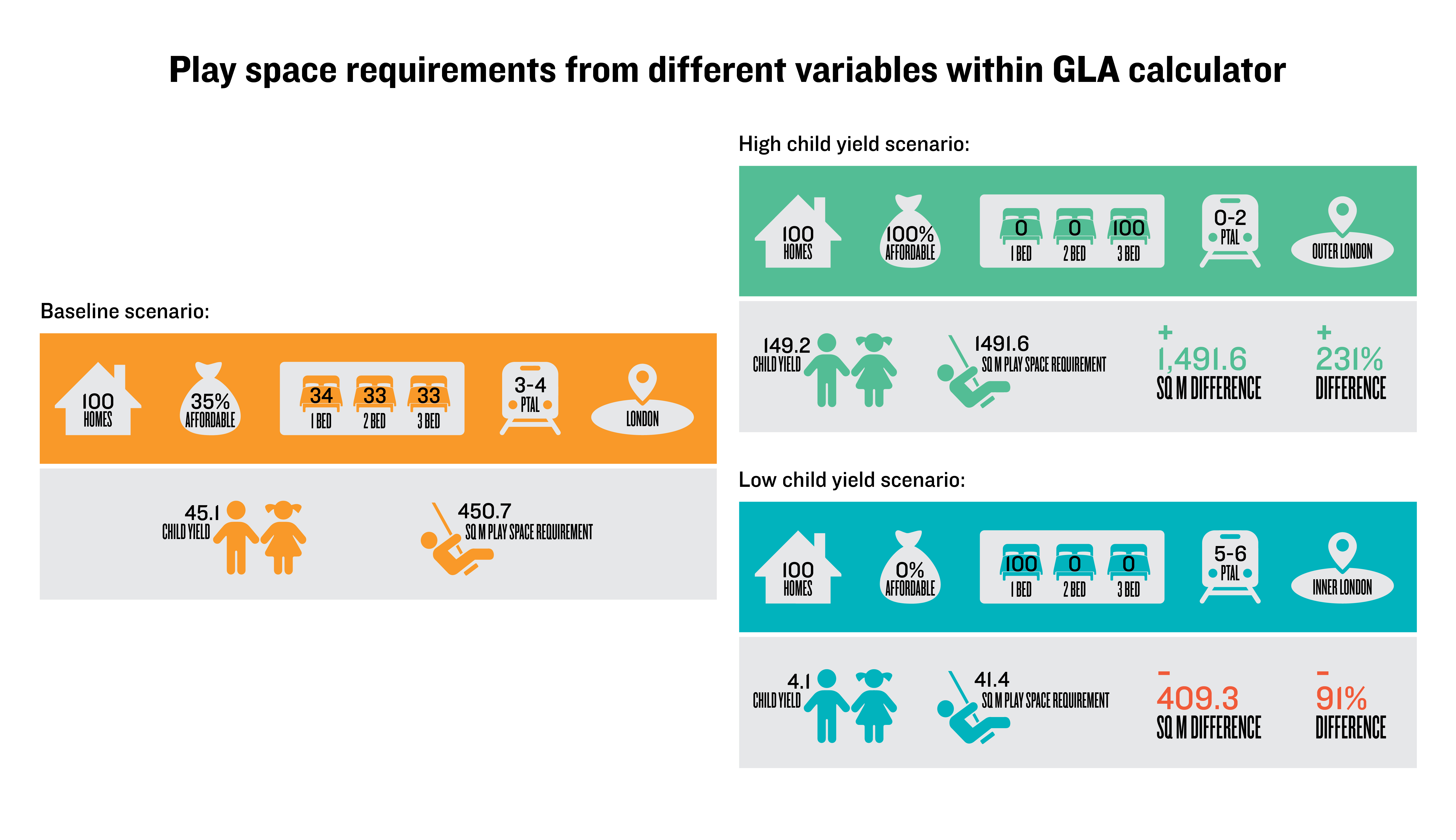

The Population Yield Calculator

You cannot have a conversation on play space without first understanding the GLA’s Population Yield Calculator (which superseded the previous GLA Play Space Calculator). In short, it works by modelling the variables listed below to produce a child yield and play space requirement (based on 10sqm per child), split by age group.

- Number of homes

- Unit mix (1 bed (inc Studio), 2 bed, 3 bed, 4 bed+)

- Tenure mix (note- intermediate homes are counted with private homes)

- Geographical aggregation (London, Inner London, or Outer London)

- PTAL (0-2, 3-4 and 5-6).

Typically, the highest play space requirements come from schemes with more homes (of course!), larger unit sizes, a greater proportion of Social Rent homes, ‘Outer London’ Geographical aggregation and lower PTAL. The difference in play space requirements can be quite dramatic, even for a modest 100-unit scheme, as illustrated in the table below:

This notional example illustrates how developments that offer the greater public benefit from housing (e.g., more social rent homes/ family sized homes) must deal with more onerous child play space policy requirements (than an open market equivalent). This can mean that schemes which deliver a high proportion of affordable housing (including Estate Regeneration projects) must work harder to balance other policy requirements and deliver a viable scheme.

It is worth noting that some LPAs use their own versions of this calculator, with the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, for example, having a calculator that removes variable such as geographical aggregation and PTAL, applying a consistent standard across the borough, regardless of accessibility.

In this context, it can be useful for developers and the design team to consider the above variables at an early stage when working on the design of schemes and engage with planning officers at the earliest possible stage to discuss the challenges, particularly on schemes that will provide a high proportion of affordable housing or larger unit sizes.

Older Childrens’ Play Space (12+)

Play space requirements are not homogenous and are split by different age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15 and 16-17).

Understandably, the London Plan has an onus on ensuring that dedicated and integrated play space for younger age groups (0-4 and 5-11) are delivered on site, given the need for door stop play with easy access and passive surveillance. However, for older age groups (12+), there is greater policy flexibility with capability for offsite provision, particularly where there are existing facilities nearby (e.g., parks), given that delivering appropriate play facilities (e.g., a sports court) can be challenging and can lead to conflicts with the amenity of residents, particularly around noise.

Accordingly, the London Plan (para 5.4.6) supports the principle of off-site provision through an appropriate financial contribution (either via CIL or in the S106 agreement), stating:

“Off-site provision, including the creation of new facilities or improvements to existing provision, secured by an appropriate financial contribution, may be acceptable where it can be demonstrated that it addresses the needs of the development whilst continuing to meet the needs of existing residents. This is likely to be more appropriate for the provision of play facilities for older children, who can travel further to access it, but should still usually be within 400 metres of the development and be accessible via a safe route from children’s homes. Schools, school playing fields and other facilities can also provide an important contribution to play and informal recreation facilities and should be encouraged to allow community access to facilities out of hours.” (Lichfields emphasis)

Whilst we find that LPAs are typically supportive of offsite 12+ play provision, we would caution that satisfying the need for existing older play facilities to be within 400 metres of the development, can prove to be stumbling block for developers, particularly in areas of insufficient existing provision. We would therefore always encourage clients and design teams to explore local provision early in the due diligence process and design feasibility so the principle of an approach to older play can be agreed with an LPA during pre-app engagement.

Balancing play space with other policy requirements

The provision of play space, particular on small urban sites, can lead to design challenges and tension, when balanced against other competing policy requirements, including providing sufficient open space for residents to use, meeting Urban Greening Factor requirements (residential schemes in London should hit a score of 0.40) and, for schemes approved from January 2024, providing Biodiversity Net Gain of 10%+.

We find this can be a tricky issue as there is an inconsistency of guidance across LPAs whether dedicated and integrated play facilities need to provide on-site for all age groups and/or if more incidental play space provision can be delivered in public realm which can also be used as, and count towards, open space. Often green spaces are multifunctional in nature, providing space for play, recreation, biodiversity enhancement and visual amenity. In this context, there can be debate on how play space is counted within a multifunctional space.

We encourage all developers and design teams to carefully consider the feasibility of meeting children’s play space and other policy requirements early in the design process and look for any opportunity for these spaces to serve multiple purposes, where appropriate, without overloading the development and diminishing from the scheme benefits.

Design Considerations

Anther issues for residential schemes in London, particularly those schemes with tall buildings, is where to locate the play space?

This is arguably more straightforward for larger sites where ground floor or podium level provision is an option as it typically allows a safe play environment with passive surveillance from surrounding homes, however, this needs to be carefully balanced with any noise amenity issues of existing residents particularly, those with private amenity space facing out on the play environment.

It can, however, be more challenging for constrained sites, say where a single tall building is proposed, as provision at grade or podium level is just not feasible and therefore alternative play options need to be explored, including terraces, internal or roof level play. Whilst the London Plan does not stipulate a preference in location, there is a difference in the approach adopted by LPAs which need to be considered early in the design process; for example, some LPAs may not be supportive of roof level play due to fire safety concerns, access and microclimate.

In any design solution, careful consideration needs to be given to accessibility to ensure there is no segregation in access to play space by tenure; for example, in a mixed tenure scheme both affordable and market residents must have equal access to the same play spaces. If play space is located a podium or roof level this can sometimes be more difficult to achieve.

Build to Rent and Co-Living

As many reading this will be aware, there has been a pronounced shift in London’s residential market over the past couple of years with growth in the Build to Rent and Co-Living sectors, compared to traditional homes for sale. This in turn, raises questions for both developers and LPAs on play space provision requirements.

Build to Rent is a C3 use and is treated the same way as traditional the homes for sale model. The only nuance is that the affordable housing requirements for Build to Rent comprise Discount Market Rent homes, a proportion of which is let at London Living Rent levels (i.e., an intermediate product); therefore, the play space requirements for such schemes would be lower than a mixed tenure for sale scheme providing social/affordable rented homes. Of course, BTR typically (but not exclusively) has a greater market demand for smaller unit sizes which in turn results in lower play space requirements.

Co-Living is markedly different given that is a sui generis use targeted towards single person households. As such, it does not attract a requirement for play space.

Gender Inclusive Play Spaces

Increasingly (and as touched on in my colleague, Georgia Crowley’s

blog) we are (understandably) seeing greater attention from architects, developers and local planning authorities in providing less gendered play environments that are welcoming for girls and young women, as well as boys

[5]. This is also reflected in the GLA’s Women, Girls and Gender Diverse good growth by design report

[6], albeit the focus of this report is focused on safety in public space rather than how play space itself is designed to be gender inclusive.

Examples of LPAs at the forefront on this include Tower Hamlets in their Regulation 18 consultation version of their emerging Plan (

here)- see Policy PS5 Gender inclusive design We would anticipate this policy direction to continue from other LPAs in their Local Plans and the GLA when they issue their updated SPG/ new LPG on Play Space.

We would therefore encourage developers to plan for this early in the design process and be cognisant of changes to policy both at a strategic and local planning authority level.

Conclusions

-

Play space important design consideration: The provision of safe stimulating, and inclusive play space is an important design consideration that needs to be designed into schemes at an early stage rather than as an afterthought. Developers should be aware of the implication of changes to housing numbers, mix and tenure on child play space numbers and requirements.

-

Offsite provision for older children: It is important to check early in the design process the location of the Site in relation to existing play space facilities and any identified under provision in the locality. Where necessary, we encourage agreement on the principle of offsite provision for older age groups is established through pre-app discussions with the LPA and any other relevant statutory bodies.

-

LPA variance in policy requirements: We recommend an early review of any local policy requirements and nuances on design and location of play space, particularly around rooftop and internal play options and acceptability of informal play provision in the public realm. We also recommend checking any LPA-specific play space calculators as these can yield different results to the GLA’s population yield calculator.

-

Alternate residential products: If schemes with Build to Rent are being explored, it is important to be aware that play space provision may be required and should be included in the scheme’s design.

-

Gender Inclusive Play Spaces: Consideration should be given at the earliest possible stage to providing gender inclusive play environments (especially for older children), that are welcoming to both boys and girls. We anticipate this will be the direction of travel for policy guidance going forward.

-

Possible update/replacement of the Shaping Neighbourhoods: Play and Informal Recreation SPG (September 2012): Finally, we would recommend keeping an eye out for any update to the GLA’s current play space Playspace SPG, to bring it in line with the London Plan 2021 and provide further guidance and direction for developers. We certainly hope that updated guidance encourages a focus on quality rather than the mechanistic application of play space standards.

The delivery of good quality play provision is increasingly recognised as a central tenet of successful housing schemes across London. London’s two million children and young people all deserve safe, stimulating and inclusive play space close to home. The planning system has a critical role to play in ensuring that good quality, appropriately located play is delivered across the capital. As ever, the Lichfields’ team is well placed to advise on your project’s play space requirements and on all other planning matters. Please do get in touch.

[1] ggbd_making_london_child-friendly.pdf

2] We understand from the ggbd ‘Making London child friendly’ that a new London Planning Guidance Document is on the way.

[3] There have been 17 draft or adopted LPG documents in the past 2 years.

[4] See London Plan (para 5.4.5) and the Making London Child Friendly, Designing Places and Streets for Children and Young People, Good Growth by Design Document

[5] For further information see: (for further information, please see my colleague, Georgia Crowley’s Blog: Breaking the biases in gendered urban environments).

[6] Safety in Public Space - Women, Girls and Gender Diverse People Revision A_0.pdf

Image credit: Ryder Architecture

Image credit: Ryder Architecture

This notional example illustrates how developments that offer the greater public benefit from housing (e.g., more social rent homes/ family sized homes) must deal with more onerous child play space policy requirements (than an open market equivalent). This can mean that schemes which deliver a high proportion of affordable housing (including Estate Regeneration projects) must work harder to balance other policy requirements and deliver a viable scheme.

This notional example illustrates how developments that offer the greater public benefit from housing (e.g., more social rent homes/ family sized homes) must deal with more onerous child play space policy requirements (than an open market equivalent). This can mean that schemes which deliver a high proportion of affordable housing (including Estate Regeneration projects) must work harder to balance other policy requirements and deliver a viable scheme.