It is exactly four years since the Independent Advisory Group (IAG) made recommendations to the Welsh Government that included making pre-application public consultations compulsory (in certain circumstances) and the question in everyone’s minds is whether or not the requirements will have the desired effect of enhancing consultation and engagement in the planning application process?

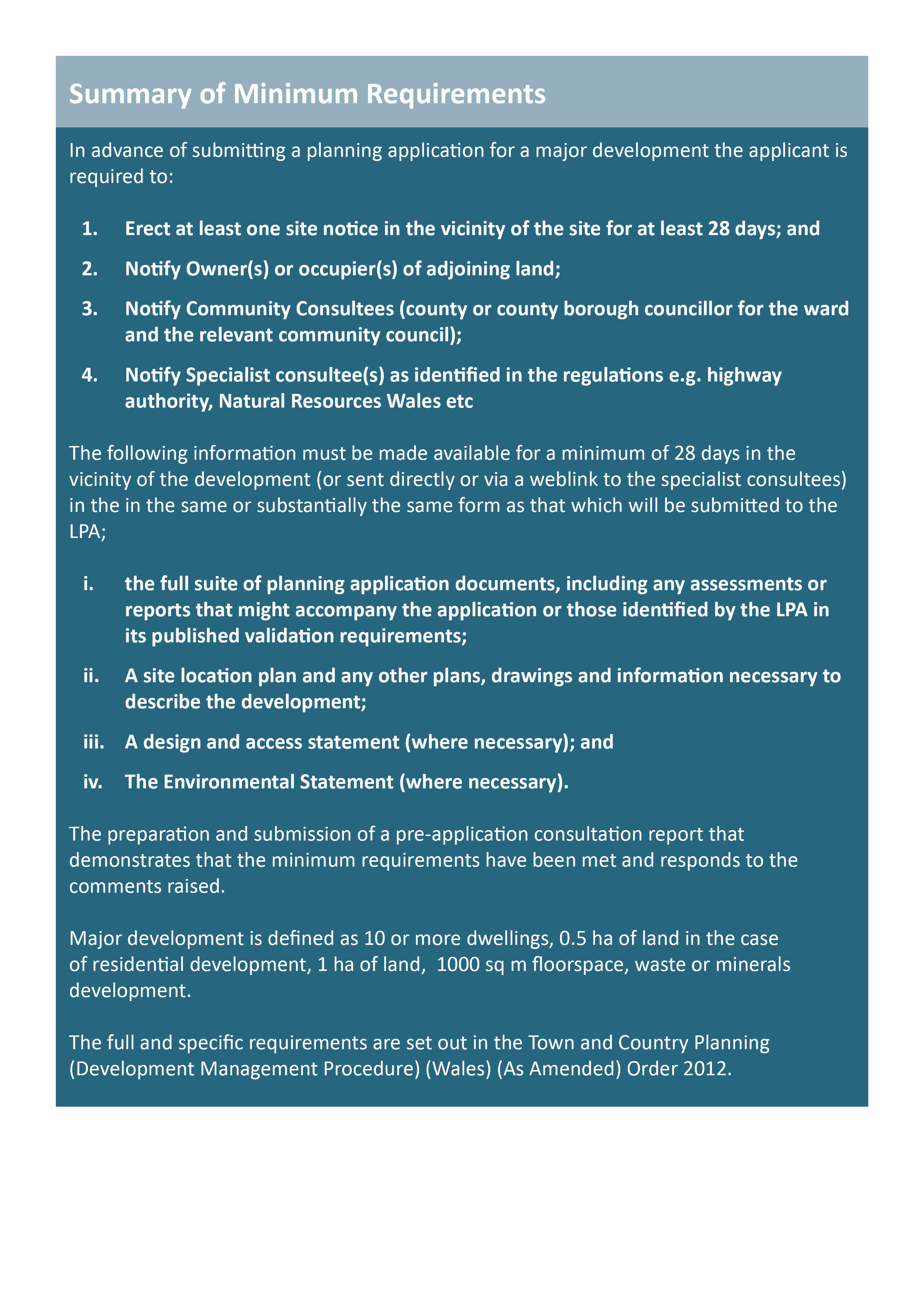

The new regulations (summarised below) require applicants to prepare a final suite of documents and then to consult with the local community as well as statutory stakeholders for a minimum period of four weeks, prior to making a planning application.

While there is certainly no zombie apocalypse on the horizon, there are grumblings and some surprise that the Welsh Government did not opt for compulsory engagement before the planning application proposals are fully worked-up. As a result, one suspects the changes will draw criticism from the community that the requirements fail to meet the recommendation of the IAG to deliver “meaningful public engagement at a time when there is an opportunity to influence design decisions”.

The new procedure has two main facets: to involve third parties (including stakeholders) at earlier stages and to seek substantive responses from specialist consultees prior to the submission of the application. The effect should be a more streamlined system in which applications can be determined within the statutory timescales and communities have an opportunity to influence the development before the submission is made.

For the applicant, will it also spell improvements to the planning system, in terms of increasing certainty? Theoretically, yes. Issues raised by the community, possibly hitherto unknown, would be considered earlier while specialist consultees are required to make substantive responses. These should result in a shorter, more certain, determination period. However, it remains to be seen whether a reduced overall programme between initial site appraisal and the completion of development (and with it, the achievement of economic and sustainable growth) will materialise.

If it results in more timely decision-making, reduces the overall development timetable and helps sustainable forms of development to come forward, then it should be welcomed as a means by which to address the continuing housing crisis and the need for other forms of development in Wales.

There are ways that NLP can help with the new pre-application statutory consultation and engagement process, in order for applicants to ensure they make best use of the changes in their development programmes:

- NLP can provide the full suite of consultation, engagement and planning services for an integrated service to our clients by applying our thought leadership as well as experience and knowledge of the planning system;

- NLP’s Smarter Engagement approach provides a focused and active strategy for consultation and engagement. It can be effectively adopted for the minimum requirements or it can be used to create a tailored strategy for any project’s needs and client objectives;

- NLP has an in-house, high quality graphic design service to produce bespoke consultation material where wider engagement forms an integral part of the planning strategy. This approach ensures that we can deliver innovative design solutions which help achieve differentiation and market advantage for our clients. Further, these can be combined with our GIS, mapping and data services that transform information and to communicate key messages effectively;

- NLP also has an in-house website design and hosting service which has a tiered approach to meeting the individual needs of any project. These range from an elementary yet client-branded display for the minimum requirements (to avoid excessive printing costs), through to fully interactive, dedicated websites updated throughout the development process for continued community engagement; and,

- NLP’s bespoke stakeholder toolkit for Wales is designed to take a systematic approach to ensuring the legal requirements of consultation are met, as well as creating efficient documentation of the process ready for preparing the Pre-Application Consultation report.