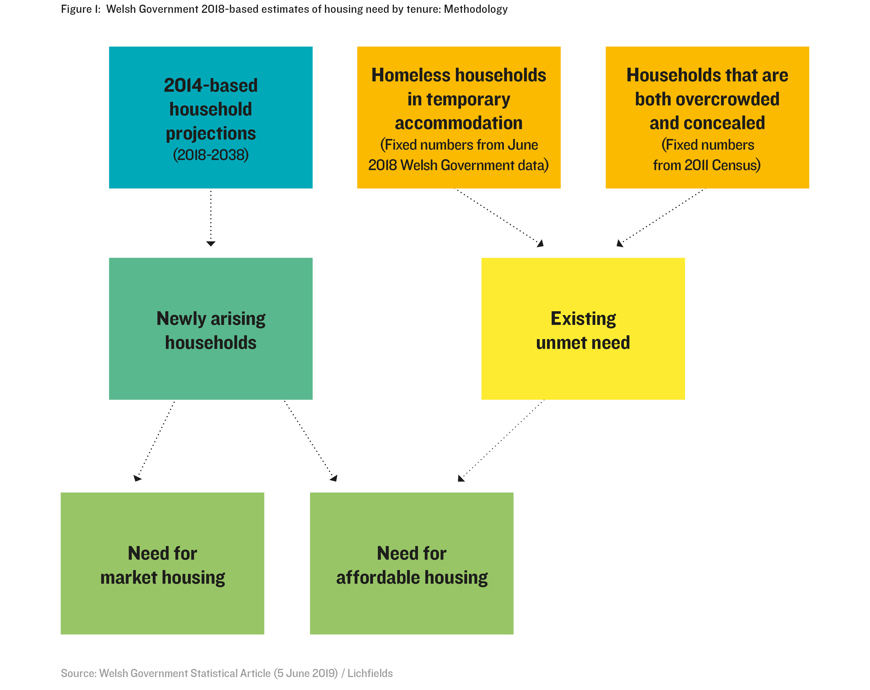

Source: Welsh Government Statistical Article (5 June 2019)

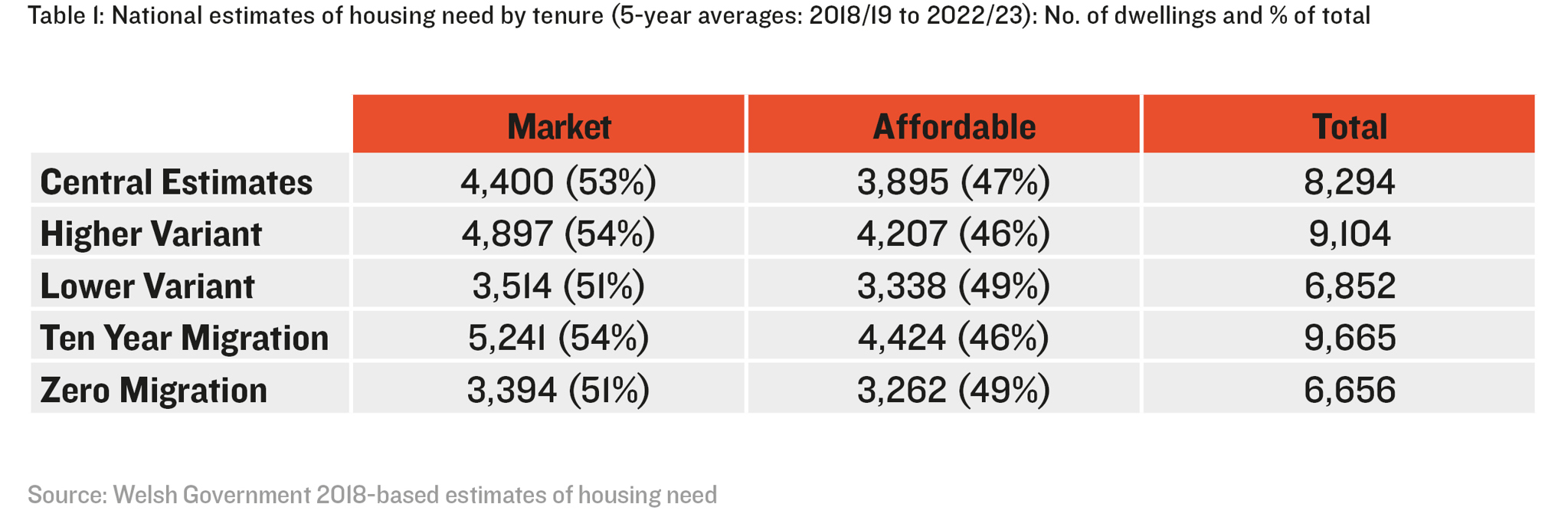

- 4,400 dwellings per annum (53%) as market housing; and,

- 3,900 dwellings per annum (47%) as affordable homes.

Source: Welsh Government 2018-based estimates housing need

These arresting figures indicate a need for almost half of all new dwellings in Wales to be provided as affordable housing. It is unclear how this level of provision could be met using existing mechanisms, given that a substantial proportion of affordable housing is delivered through section 106 agreements, where viability considerations will (to a greater or lesser extent) limit the proportion of affordable homes that can be provided. Experience from existing viability assessments demonstrates that even in the strongest market areas affordable housing provision is rarely higher than 25 to 30%. In many parts of Wales, the level of provision that can be justified is significantly lower.

By comparison, in the 20 years from 1999/2000 to 2018/19, affordable housing constituted only 11% of all completions. This indicates that a requirement for almost half of all housing delivery to constitute affordable homes is not realistic under current delivery mechanisms.

If increased levels of affordable housing are to be delivered this will have to be accomplished in ways outside of the traditional section 106 approach. There is also a need to consider the extent to which overall housing delivery should be increased to help deliver additional affordable homes through section 106 agreements. For example, while the delivery of 3,900 affordable homes per annum would not be feasible under a requirement for 47% affordable housing (out of a total of 8,300 homes), it would be more likely as a smaller proportion of a larger overall housing requirement (e.g. 30% of a total of 13,000 homes). Increasing overall housing delivery would also have the added benefit of improving affordability of open market housing.

It is therefore imperative that policymakers heed the Welsh Government’s admonition that these figures should not be translated directly into housing targets. As is the case with the overall housing need estimates, the Welsh Government has clearly stated that they are merely intended to form a basis for discussion to aid policy decisions. If enacted in policy, the published figures would serve to choke off essential delivery of all types of housing, as development would simply be unviable.

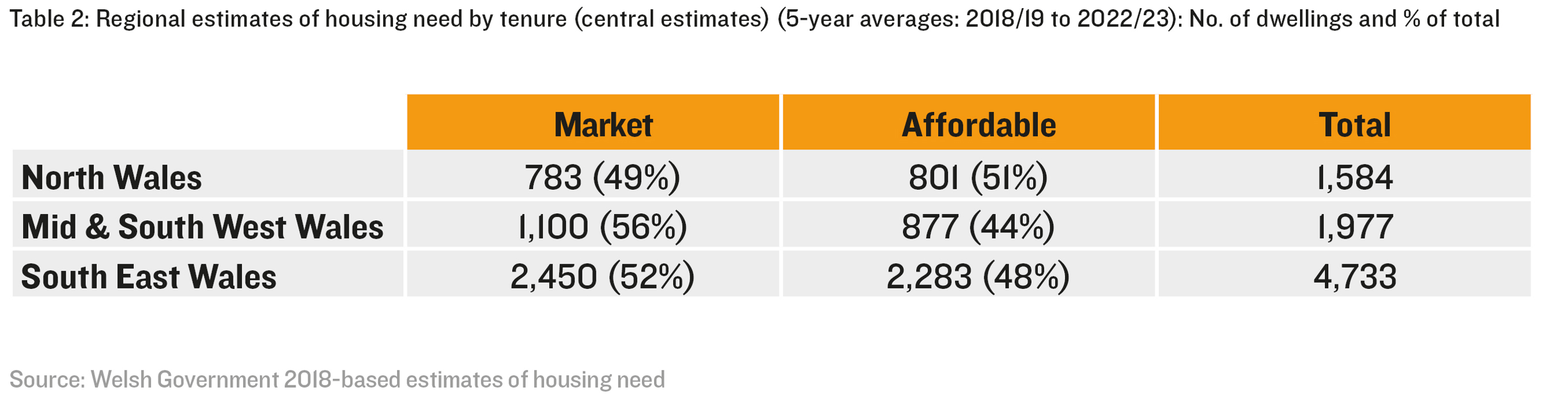

The tenure breakdown of the central estimates for the three identified regions of Wales (2018/19 to 2022/23) is indicated in Table 2.

Source: Welsh Government 2018-based estimates of overall housing need

The key assumptions that can be flexed include:

- Household projections (official projections or modelling provided by the user);

- Existing unmet need;

- Household income (current and future (and distribution));

- Private rental prices (current and future); and,

- Affordability criteria.

The tool also enables a further breakdown into a total of four tenures, with market housing split into owner occupied and private rented and affordable housing split into intermediate and social rented.

The Welsh Government has recognised that adjustments to the assumptions applied within each of the model’s criteria can make a significant difference to the estimates for Wales and its regions. For example, the default assumption is that households that can afford a 2- or 3-bedroom property based on spending 30% of their household income should be considered suitable for market housing. When considering this variable, policymakers should be careful not to assume that it is acceptable for households to spend large proportions of their income on housing out of necessity. If the affordability threshold is reduced from 30% to 25% of household income, the proportion of need for affordable housing would increase from 47% to 55% in the central estimates for Wales.

It is therefore vital that policymakers test a range of possible scenarios when setting housing requirements. This is particularly important given the current national context of economic uncertainty.

The publication of the estimates of housing need by tenure is to be welcomed as a credible starting point for the assessment of need that will inform housing requirements in the emerging NDF and forthcoming SDPs. More importantly, it is reassuring to see that the Welsh Government has acknowledged the need to test the impact of different assumptions and has highlighted a number of these sensitivities. However, it is vital that the estimates are treated as a starting point only.

What is noticeably absent from the analysis is a consideration of the links between homes and jobs, which are so important for the functioning of sustainable communities. In South East Wales, the Cardiff City Deal is seeking a step change to achieve “truly transformational change” in order to boost the local economy. This will rely on moving away from past trends (which are reflected in the 2014-based household projections) to result in different outcomes in the future.

Fundamentally, the estimates do not (and cannot, as policy-neutral statistics) seek to identify the number and tenure split of homes required to attract and retain workers to support the Welsh economy. It is therefore up to policymakers to take this next step to ensure that housing and economic objectives are aligned in the emerging NDF and future SDPs.

[1] Including Help to Buy and Intermediate Low Cost Home Ownership (e.g. Homebuy and Shared Ownership)

[2] This differs slightly from the Technical Advice Note 2 Planning and Affordable Housing (2006) definition of affordable housing, which includes intermediate housing for purchase, including via equity sharing schemes (for example Homebuy).