The final version of the revised National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) was published on 24 July 2018, on the very last day before summer Recess and avoiding Parliamentary debate. In contrast, the draft version (published in March for consultation) had been announced by the Prime Minister Theresa May at a dedicated launch event.

Much has changed in the make-up of Government in the four months since the consultation started (not least, the Housing Secretary and Housing Minister); however, and notwithstanding the huge amount of responses received (almost 30,000), changes made to the final version of the revised NPPF focus on clarifications and re-wording, with very few more significant amendments.

Naturally, wider implications and potential impacts of the new policies will become clearer over time; for now, we have identified eleven points where changes have been made following the draft NPPF’s consultation and which are worth bearing in mind.

1. Using design policies as a key to boosting house building

The revised NPPF gives a new centrality to design policies, as they are considered instrumental in delivering new homes. In his Written Ministerial Statement announcing the launch of the revised Framework, Housing Secretary James Brokenshire said:

‘[…] Critically, progress must not be at the expense of quality or design. Houses must be right for communities. So the planning reforms in the new Framework should result in homes that are locally led, well-designed, and of a consistent and high quality standard.’

Chapter 12 ‘Achieving well-designed places’ is where this renewed rhetoric is translated into policy. Paragraph 124 specifies that ‘being clear about design expectations, and how these will be tested, is essential’ for achieving sustainable development. Effective engagement e.g. with local communities (including through workshops), the use of ‘local design standards or style guides’, and the refusal of permissions for developments of poor design are some of the ways the revised NPPF aims to achieve this objective.

Crucially, para 130 requires local planning authorities (LPAs) to make sure that the quality of approved developments does not materially diminish ‘between permission and completion, as a result of changes being made to the permitted schemes’.

2. Planning application viability assessments as exception to be justified

The front-loading of viability assessment at plan-making stage (rather than when determining applications) was already anticipated by the draft revised NPPF, as the expectation was to be for plans to set out the levels and types of affordable housing and other infrastructure that would be required from proposed developments.

However, changes included in the final version are quite significant when compared to both the original NPPF and the draft revision, particularly around paragraphs 34 and 57.

The revised NPPF’s paragraph 34 on development contributions removes the possibility for plans to set out circumstances when further viability assessment may be required in determining individual planning applications. The reasoning is in para 57: the revised NPPF puts the burden on applicants ‘to demonstrate whether particular circumstances justify the need for a viability assessment at the application stage’.

Furthermore, para 57 goes on to state that it will be for the decision maker to decide about the weight to be given to the viability assessment ‘having regard to all the circumstances in the case’ (including whether the plan/evidence is up to date, and potential changes to site circumstances).

3. Standardised methodology and Housing Delivery Test confirmed (for now)

The new standardised methodology to assess housing needs and the Housing Delivery Test are two of the most anticipated changes to housing policy that the Government is bringing forward, and they are reflected in the revised NPPF (and accompany documents).

Unsurprisingly, neither has been significantly amended when compared to previous consultation versions, probably reflecting the inherent complexities behind their ‘construction’. However, of interest in relation to the standardised methodology is the Government response to the draft revised NPPF consultation which highlights:

‘[…] it is noted that the revised projections are likely to result in the minimum need numbers generated by the method being subject to a significant reduction, once the relevant household projection figures are released in September 2018. In the housing White Paper the Government was clear that reforms set out (which included the introduction of a standard method for assessing housing need) should lead to more homes being built. In order to ensure that the outputs associated with the method are consistent with this, we will consider adjusting the method after the household projections are released in September 2018. We will consult on the specific details of any change at that time.’

In short, the methodology is confirmed for now, but everything may change, following the release of household projections in September 2018 (see this

Lichfields blog for further details).

4. Lower requirement for small (and medium) sized sites

The draft revised NPPF’s requirement for at least 20% of the sites identified by LPAs in their plans to be half a hectare or less has been changed and potentially made more achievable.

The final version of the revised NPPF now expects LPAs to accommodate at least 10% of their housing requirement on ‘small and medium sized sites’ (up to one hectare) through their development plans and brownfield land registers. Furthermore, it is recognised that the 10% target may not be achievable in all circumstances; in such cases, the preparation of the relevant plan policies should detail the ‘strong reasons’ that make the target unachievable.

5. More clarity on strategic and non-strategic policies

The draft NPPF’s reference to ‘strategic’ and ‘local’ policies - which caused confusion in relation to spatial development strategies, and appeared to undermine the need for local plans - has been clarified.

The final revised NPPF now distinguishes between strategic policies (which should look over a minimum of a 15-year period) and non-strategic policies (included in local plans, when these are not considered strategic policies, and in neighbourhood plans). Both ‘strategic’ and ‘non-strategic’ policies are defined in more detail in Annex 2: Glossary.

6. Town centre diversification promoted

The rapid changes that are affecting the retail sector and, as a consequence, England’s town centres are acknowledged and reflected in the final version of the revised NPPF. It recognises that diversification is key to the long-term vitality and viability of town centres, to ‘respond to rapid changes in the retail and leisure industries’. Accordingly, planning policies should clarify ‘the range of uses permitted in such locations, as part of a positive strategy for the future of each centre’.

The draft revised NPPF’s reference to town centres in decline has been removed, possibly because of its unclear wording and most probably in wider recognition of the effects that changed shopping habits are already having on town centres.

7. Land assembly and compulsory purchase

Reflecting wider debates about the role of LPAs in bringing forward enough land for housing developments to meet their identified needs (and the Government’s 300,000 homes/year target), paragraph 119 now details some of the powers that proactive LPAs should use.

These include specific reference to facilitating land assembly, where possible, and using compulsory powers where this is considered beneficial to ‘meeting development needs and/or secure better development outcomes’.

8. Green Belt: of course it’s here to stay

Unsurprisingly, Green Belt policies have not changed significantly from the draft version published for consultation; however, two minor changes in wording are of interest.

Paragraph 136 on exceptional circumstances to amend Green Belt boundaries now refers to these being ‘fully evidenced and justified’, an addition since the draft revised version. While this might appear to be a more stringent requirement, new para 137 specifies that, to justify the existence of exceptional circumstances, an LPA ‘should be able to demonstrate that it has examined [it was ‘should have examined’] fully all other reasonable options for meeting its identified need for development’; this might seem like a minor change, but it could give more flexibility and a clearer path for LPAs considering releasing Green Belt in exceptional circumstances.

9. Heritage policies retained and restored

Heritage and historic environment policies are generally in line with those proposed in the draft revised NPPF. Importantly, LPAs are now expected to maintain ‘or have access to’ a historic environment record (paragraph 187). One of its purposes is to be used to ‘predict the likelihood that currently unidentified heritage assets […] will be discovered in the future’.

Changes to the way the impact of proposed development on the significance of designated heritage asset is assessed, which were already anticipated in the draft revised NPPF, are now confirmed and further clarified; paragraph 193 states that ‘great weight should be given to the asset’s conservation […] irrespective of whether any potential harm amounts to substantial harm, total loss or less than substantial harm to its significance’.

Finally, where a development proposal will lead to less than substantial harm to the significance of a designated heritage asset, ‘this harm should be weighed against the public benefits of the proposal including, where appropriate, securing its optimum viable use’. The term ‘optimum viable use’ was included in the original NPPF but not in the draft revised NPPF.

10. A change to transition

The policies in the revised NPPF are material considerations to be taken into account in determining planning applications ‘from the day of its publication’ (i.e. from 24 July 2018).

Importantly, the policies in the 2012 NPPF still apply to examining plans submitted on or before 24 January 2019.

Interestingly, footnote 69 is amended to clarify that for spatial development strategies, ‘submission […] means the point at which the Mayor sends to the Panel copies of all representation made’; this is an amendment specifically made to reflect the stage reached by the draft London Plan, particularly when compared to the draft revised NPPF wording (which referred to ‘submission’ being a later stage, specifically the point in which copies of the strategies intended for publication are sent to the Secretary of State).

Accordingly, the new draft London Plan will be examined against the original NPPF policies – a relief to the Mayor no doubt.

11. ‘Social rent’ back in and starter homes loosen up

The revised version of the glossary at Annex 2 includes reference to social rent again, as an ‘affordable housing for rent’ product rather than in its own right; any reference to social rent housing was previously deleted from the draft revised NPPF’s definition of affordable housing.

Further amendments have been made to the definition of ‘affordable housing’, particularly in relation to starter homes. Interestingly, previous reference to the maximum annual household income of eligible buyers (£80,000, or £90,000 in London) has now been removed and left as a matter for secondary legislation; this is to reflect the fact that the Housing and Planning Act 2016 does not explicitly refer to those income thresholds.

Might this signal the ‘resurgence’ of starter homes? Unlikely.

Overall, the impression is that the process of updating and reviewing the 2012 NPPF has been more complicated than many expected it to be, and the continuous changes in the Department and then Ministry surely have not helped (five Housing Ministers and three Secretaries of State since the NPPF review was first announced).

Perhaps as a result of it having taken a good while, the revised NPPF seems to better reflect the new approach taken by the Ministry, the renewed centrality that housing policies have within the Government’s agenda and all of the case law that has come about from testing the 2012 Framework in the courts. The new NPPF even reflects Sir Oliver Letwin’s emerging findings on housing delivery, by effectively recognising that the quality and design of housing development is crucial to ensuring greater community support.

Some reforms do seem ambitious, particularly around viability assessments and given the English plan-led system, and the practical impacts of these reforms ought to be tested and monitored over a longer period of time to understand whether Government has struck the right balance.

As acknowledged in James Brokenshire’s Written Ministerial Statement, the revised NPPF alone will not be enough solve the housing crisis; other reforms, the support of central Government, cooperation with/between stakeholders, local authorities and communities are all crucial elements in addressing the housing challenges the country is facing.

As usual in these cases, whether the revised NPPF represents a new beginning or rather a false start is too soon to be said, as its final judgement will be solely based on its achievements and/or failures.

See the ‘Revised National Planning Policy Framework’ suite of documents here

Lichfields will publish further analysis of the consultation on the draft revised NPPF and its implications.

Click here to subscribe for updates.

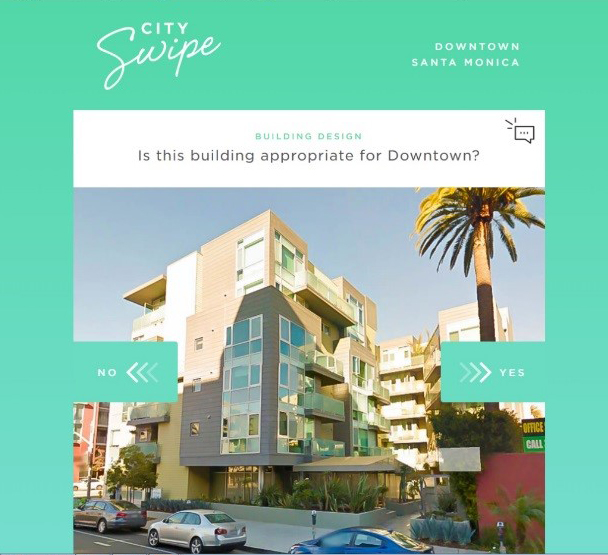

Downtown Santa Monica City Swipe App (Source: dtsmcityswipe.com)

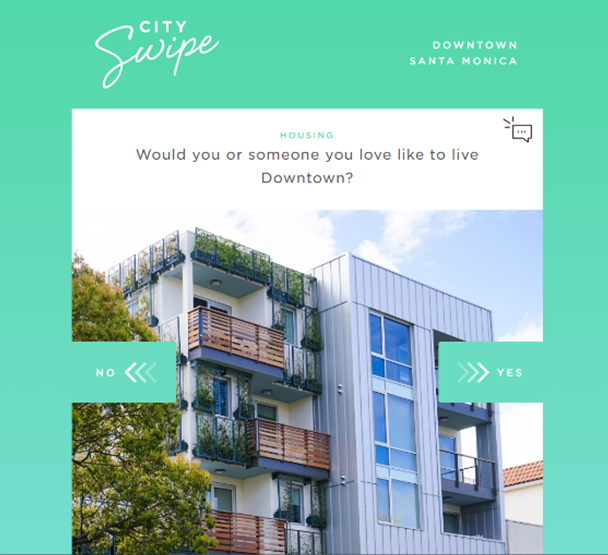

Downtown Santa Monica City Swipe App (Source: dtsmcityswipe.com)

Downtown Santa Monica City Swipe App (Source: dtsmcityswipe.com)

Downtown Santa Monica City Swipe App (Source: dtsmcityswipe.com)