Image credit: Jamie Fobert Architects + Purcell

Our award winning blog gives a fresh perspective on the latest trends in planning and development.

Image credit: Jamie Fobert Architects + Purcell

What is cultural infrastructure?

Cultural infrastructure, whilst critical to London’s economy, is often ill-defined. The Plan states this infrastructure encompasses the buildings, structures and places where culture is either consumed or produced. With the recent announcement of the Creative Enterprise Zones – the first ones being designated in December 2018 – we are seeing an increasing emphasis placed upon the creative economy; a sector which generates ‘£52bn for London each year, is the reason most tourists visit, [and] employs one in six Londoners’.[2] Our cultural spaces, beyond contributing to ‘cultural wellbeing’, are critical in terms of job creation, sector growth and maintaining London’s position as a world leader in cultural capital.

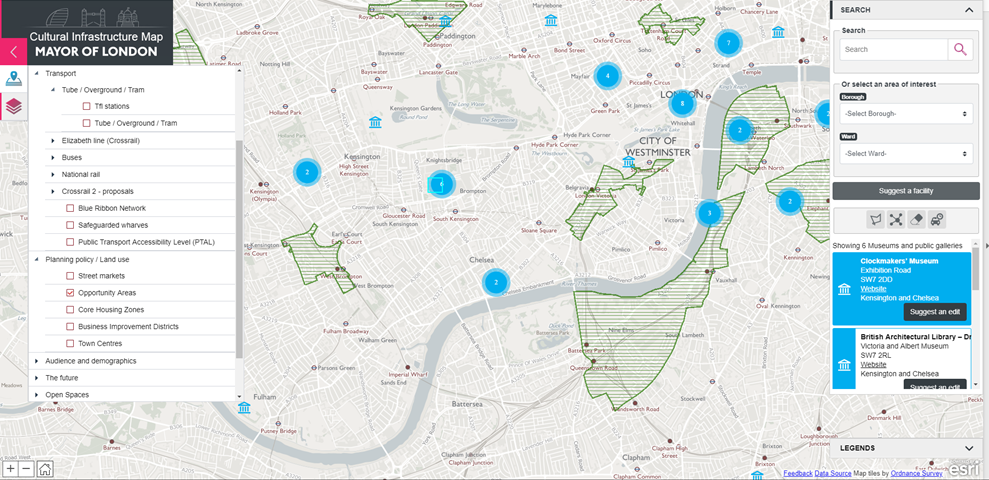

The Mayor’s Plan stresses the need to map this cultural infrastructure across the Capital to plan effectively. The cultural infrastructure map allows users to choose from 36 indicators (spanning from artists workspaces, community centres, dance halls, heritage at risk, pubs and theatres) to explore different locations across the Capital. The map (see extract, below), allows cultural spaces to be viewed at both Borough and Ward level. This can then be combined with context layers such as transport, planning policy, audience and demographics, and open spaces. For instance, the map below shows the results of combining the museums indicator with the Opportunity Zone context layer. Developers, planners and architects proposing new developments are encouraged to consider cultural spaces, particularly those deemed to be at risk, and seek to incorporate these spaces within their proposals.

Source: The Cultural Infrastructure Map (2019)

Planning for cultural infrastructure

Whilst we are already seeing a number of co-operative solutions being implemented across the Capital, more is needed to sustain our world class cultural assets which are vital to both London’s economy and our sense of cultural wellbeing. The Mayor seems resolute that planners must play a key role in delivering future cultural spaces to enable our creative economy to thrive and for all of London to enjoy. As the Cultural Infrastructure Plan states, a first step must be for planners to answer this call to action.

[1] National Planning Policy Framework, (2019), paragraph 8[2] The Cultural Infrastructure Plan, Greater London Authority, (2019) p.7[3] The Cultural Infrastructure Plan, GLA, (2019), p.35[4] The Cultural Infrastructure Plan, GLA, (2019), p.38[5] The Cultural Infrastructure Plan, GLA, (2019), p.40

Lichfields is currently monitoring the draft London Plan Examination in Public (EiP), which is scheduled to last until May 2019, and will report on relevant updates as part of a blog series. The seventh blog of the series focuses on some key further suggested changes proposed by the Mayor.

After months of hectic hearing sessions, lengthy written statements, endless words, minor suggested changes, followed by further suggested changes, we are now officially in the break-month of the London Plan Examination in Public (EiP), which will duly resume at the end of April.

In this context, you might well be forgiven for having lost the plot over where we are at with the draft London Plan, and the latest GLA position on some of the more contentious proposed policies. Whilst, we are still far from knowing any official recommendation from the Planning Inspectors (with the Inspectors’ report currently expected sometime in Summer 2019), the break creates an opportunity to look back at some of the changes the GLA has officially endorsed via published further suggested changes.

Below, I have listed six key policy changes (plus a little bonus) which are likely to significantly affect the development sector in London, if endorsed and confirmed by the Inspectors. All the references below to draft London Plan policies/paragraphs are taken from the latest version of the whole Plan (published August 2018, available here).

1. Housing targets and monitoring: a steep stepped approach?

One of the main concerns for London Boroughs has surely been the high annualised housing targets (set out in table 4.1 in the draft Plan) and their immediate application from April 2019. The GLA seems to have accepted that it is unrealistic (and procedurally questionable, given that the Plan is not yet adopted) for London Boroughs to step-up their housing delivery at the levels the GLA envisages from year one.

Accordingly, it proposes to allow Boroughs to increase their housing targets gradually, allowing them ‘to set out a realistic, and where appropriate, stepped housing delivery target over a ten-year period’ (Paragraph 4.1.3[1]). This might provide a short-term solution to address under-delivery in the first years, but the cynics among us might say that it will simply allow Boroughs to kick the can down the road.

Interestingly, the proposed change also touches on another very contentious point, this being the interplay between proposed housing targets, the Government’s standard method for assessing housing need, and the Housing Delivery Test. Boroughs wishing to opt for a stepped housing delivery target are to clearly articulate ‘how these homes will be delivered and any actions the boroughs will take in the event of under-delivery’; the draft Plan now notes that a ‘clear articulation […] would also fulfil the requirement of a ‘Housing Delivery Test action plan’’.

Notwithstanding the questions raised by London Boroughs on the potential impacts of this ad-hoc regime (with the new London Plan based on the 2012 NPPF, while Local Plans will be based on the 2019 NPPF), MHCLG concerns about London’s deviation from the standard method for assessing local housing need, and the draft Plan’s reference to the Housing Delivery Test, the Mayor seems firm in his view that housing delivery in London should be assessed against his targets, rather than the standard method-derived housing requirements.

This makes for a policy area of the draft London Plan worth following, particularly to understand what the Inspectors will recommend in light of these differing views between the Government and the GLA, as well as for the potential practical implications it may carry.

2. Small sites: yet, not too small to contribute

3. Affordable Housing or employment land, that is the question

4. Industrial land: exempting from the plot (ratio)

Still on industrial land policies, significant debate emerged at the related hearing session on the introduction of a minimum floorspace plot ratio of 65% (industrial floorspace/total land) as benchmark against which the principle of ‘no net loss’ of industrial floorspace capacity should be measured. In the draft London Plan industrial floorspace capacity is defined ‘as either the existing industrial and warehousing floorspace on site or the potential industrial and warehousing floorspace that could be accommodated on site at a 65 per cent plot ratio (whichever is the greater)’[8].

However, the GLA recognises that not all industrial uses might be able to operate or being commercially viable if a strict 65% floorspace plot ratio were to apply. Accordingly, a further suggested change provides for exceptional circumstances, where ‘it should be demonstrated that it is not feasible to achieve no net loss of industrial floorspace capacity through alternative configurations, multi-storey industrial development, a wider mix of industrial uses, or other appropriate measures’ (Supporting text 6.4.5AB[9]). However, this exceptional approach will not apply to industrial developments proposed as part of SIL/LSIS consolidation processes, and for industrial/residential/non-industrial co-location schemes.

5. Green Belt and Metropolitan Open Land: national policy and no land-swap

Bonus track: live hub of planning data

The draft London Plan: a marathon, not a sprint

[1] Appendix 1: M19 Further Suggested Changes[2] Appendix 2: M20 Further Suggested Changes[3] ’For the purposes of part D, the presumption in favour of small housing developments means approving proposals for small housing developments which are consistent with the policies of the London Plan while recognising that local character should evolve over time to provide new homes’ (Policy H2 E, Matter 20 Further Minor Suggested Changes to Policy H2)[4] Matter 20 Further Minor Suggested Changes to Policy H2[5] Appendix 1: M29 Further Suggested Changes[6] Appendix 1: M24 Further Suggested Changes[7] Appendix 1: M24 Further Suggested Changes[8] Supporting text at paragraph 6.4.5 (The draft London Plan showing minor suggested changes, August 2018)[9] Matter 62: Land for Industry, Logistics and Services, Further Suggested Changes[10] Mayor of London Written Statement on M65 Green Belt and Metropolitan Open Land[11] Matter 65 Further suggested changes to be made to Policy G3 Metropolitan Open Land[12] Matter 60: Low Cost and Affordable Business Space Further Suggested Changes[13] A live hub of planning data for London – update (Medium)

Draft London Plan EiP: A new hope for industrial land?

Draft London Plan EiP: Heritage and culture are now dusted

Draft London Plan EiP, Affordable Housing: 3D snakes and ladders

Draft London Plan EiP: ‘Willing Partners’ or not?

Draft London Plan EiP: Design – fit for purpose?

This blog has been written in general terms and cannot be relied on to cover specific situations. We recommend that you obtain professional advice before acting or refrain from acting on any of the contents of this blog. Lichfields accepts no duty of care or liability for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting as a result of any material in this blog. © Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 2019, trading as Lichfields. All Rights Reserved. Registered in England, no 2778116. 14 Regent’s Wharf, All Saints Street, London N1 9RL. Designed by Lichfields 2019.

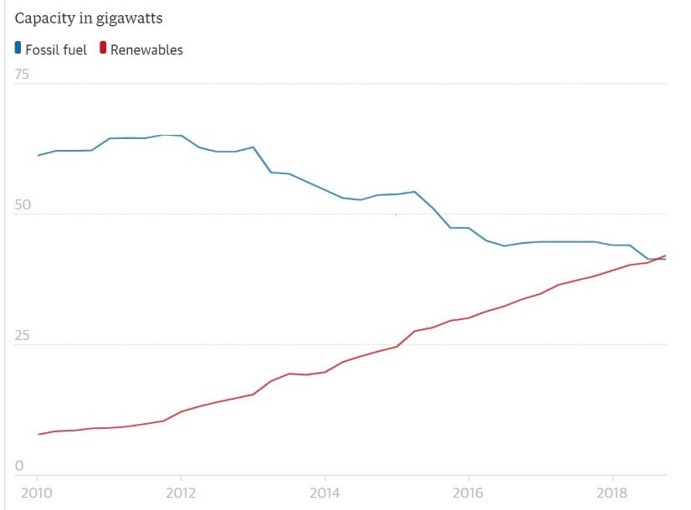

A Changing Energy Mix

The UK’s energy mix is undergoing a process of rapid change in response to the global ambition to drastically limit global warming this century. The dependence on traditional methods of energy production is decreasing, and renewable energy is growing rapidly as a source of power generation. The capacity of renewable energy overtook fossil fuels in the UK for the first time ever in 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Renewable Energy Capacity Has Overtaken Fossil Fuels in the UK

Source: Guardian Graphic, Imperial College London, Drax (6th November 2018)

However, an increasing reliance on intermittent renewables such as wind and solar energy provision can create problems. As we make the switch to a more intermittent and less flexible low carbon generation mix, there is an emerging need to ensure that energy supply is resilient. Planning has a vital role to play in facilitating the provision of energy infrastructure in a timely way to ensure a consistency of supply.

This blog will explore how the planning system can strengthen its enabling role both at national and local level, with battery storage providing an important emerging technology to support the diversification of the energy market.

What we mean with battery storage?

Figure 2 battery storage Facility in the UK

Source: Edie.net (Edie Newsroom - 15th January 2019)

What changes are proposed in National Policy?

Large-scale storage projects with a generating capacity of more than 50MW are currently considered under the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIP) regime, introduced by the Planning Act 2008, with smaller schemes decided by Local Planning Authorities (LPAs).

At national level in England, the way energy storage projects are assessed by the planning system has been the focus of a recent Government consultation titled ‘The treatment of electricity storage within the planning system’, which closed on 25th March 2019. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy’s (BEIS) consultation sought to determine how best it can alter planning regulatory frameworks to support developers and businesses seeking to build energy storage facilities in England.

Local Plans: unfit for purpose?

The main pre-requisite for Battery Storage schemes is a connection to the electricity grid, and the locational requirements of such schemes present a significant constraint for their widespread implementation. This is because a storage facility must either be developed within close proximity to an existing power plant or sub-station with spare capacity, or brought forward alongside renewable energy infrastructure.

Currently, local plans provide nowhere near enough support to effectively enable implementation, and are largely ill-equipped to efficiently deal with the requirements of this emerging technology. LPAs must consider the way their local plans approach Battery Storage development, with particular regard to increasing delivery through the following actions:

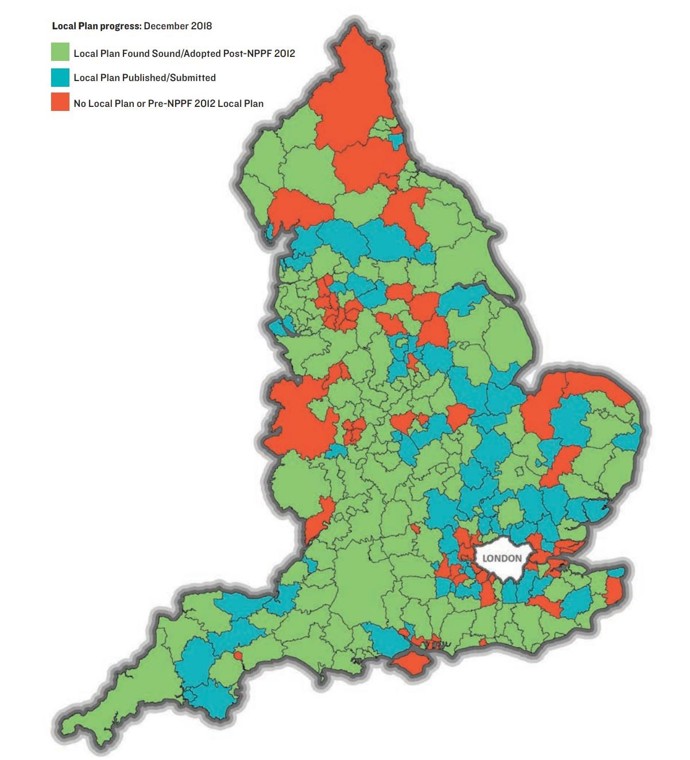

Scope certainly remains to improve and maximise the ability of the planning system to help deliver these facilities on a widespread scale. Though an ability to improve delivery also relies somewhat on LPAs having an up-to-date, ‘modern’ local plan in place, with many LPAs across England yet to adopt innovative policies in this field.

This particular issue is highlighted in Figure 3 below, which illustrates local plan status post- original NPPF (2012). Just over 55% of LPAs have a post-NPPF 2012 plan in place as of December 2018.

Figure 3 Local Plan Status post-NPPF 2012 by LPA as at 31st December 2018

Source: Lichfields analysis

Conclusions

[1] Science for Environment Policy: Towards the battery of the future (September 2018)

[2] Reuters: Britain outlines plans for 2025 coal-power phase out (January 2018)