The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government [MHCLG] recently announced that it would be postponing the results of the 2019 Housing Delivery Test [HDT] until after December's general election. This is due to ‘purdah’ rules, which forbid government departments from making political announcements during an election campaign

[1].

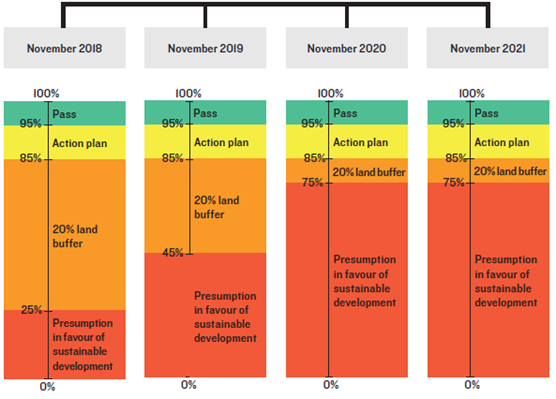

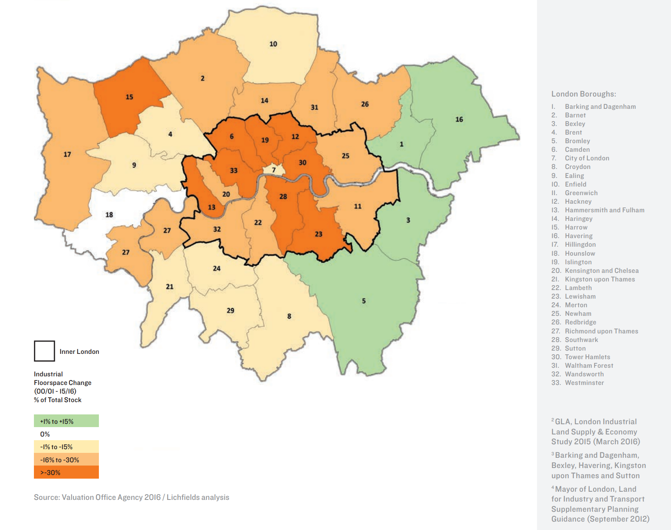

As many will now be aware, the HDT forms the basis for assessing whether Councils are delivering the homes they need, by comparing past housing delivery to housing need. A series of graded ‘penalties’ are imposed depending on the extent of any shortfall (Figure 1), with the bar continually raised up to November 2020.

Figure 1 Housing Delivery Test Thresholds

Source: MHCLG; Lichfields

If a Council falls below 95% of their required delivery, they will be expected to produce an Action Plan within 6 months which:

- Identifies the reasons for under delivery;

- Explores ways to reduce the risk of further under-delivery; and,

- Sets out measures the authority intends to take to improve levels of delivery.

However, it is unclear what the sanction will be for Councils that fail to comply with this requirement. The 2018 HDT results were published back in February 2019, and yet a number of authorities in the North West [NW] have yet to produce their required Action Plan.

This blog explores this lack of action in more detail and provides analysis of the Action Plans which have been produced in the NW so far.

Who has produced an Action Plan?

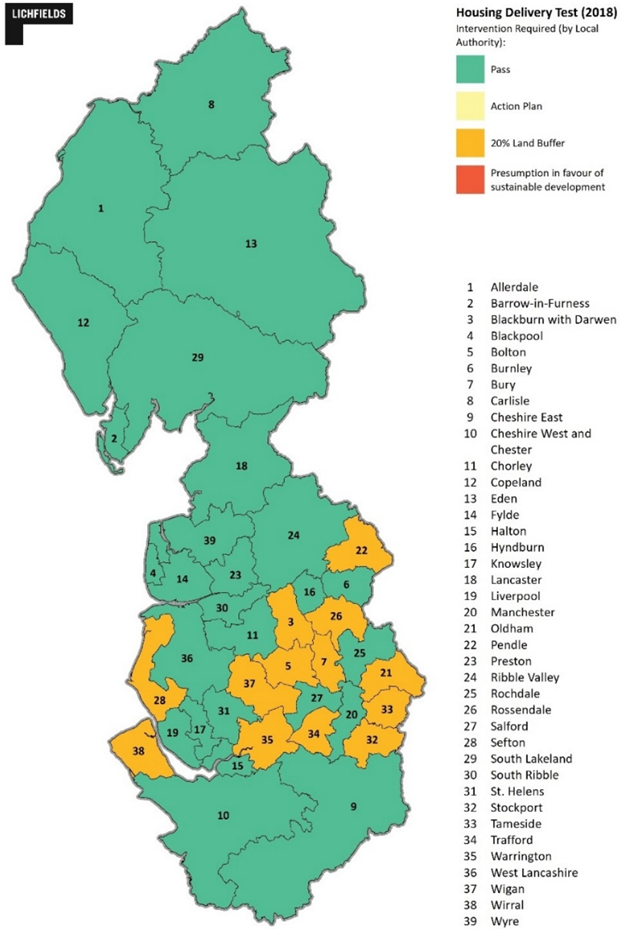

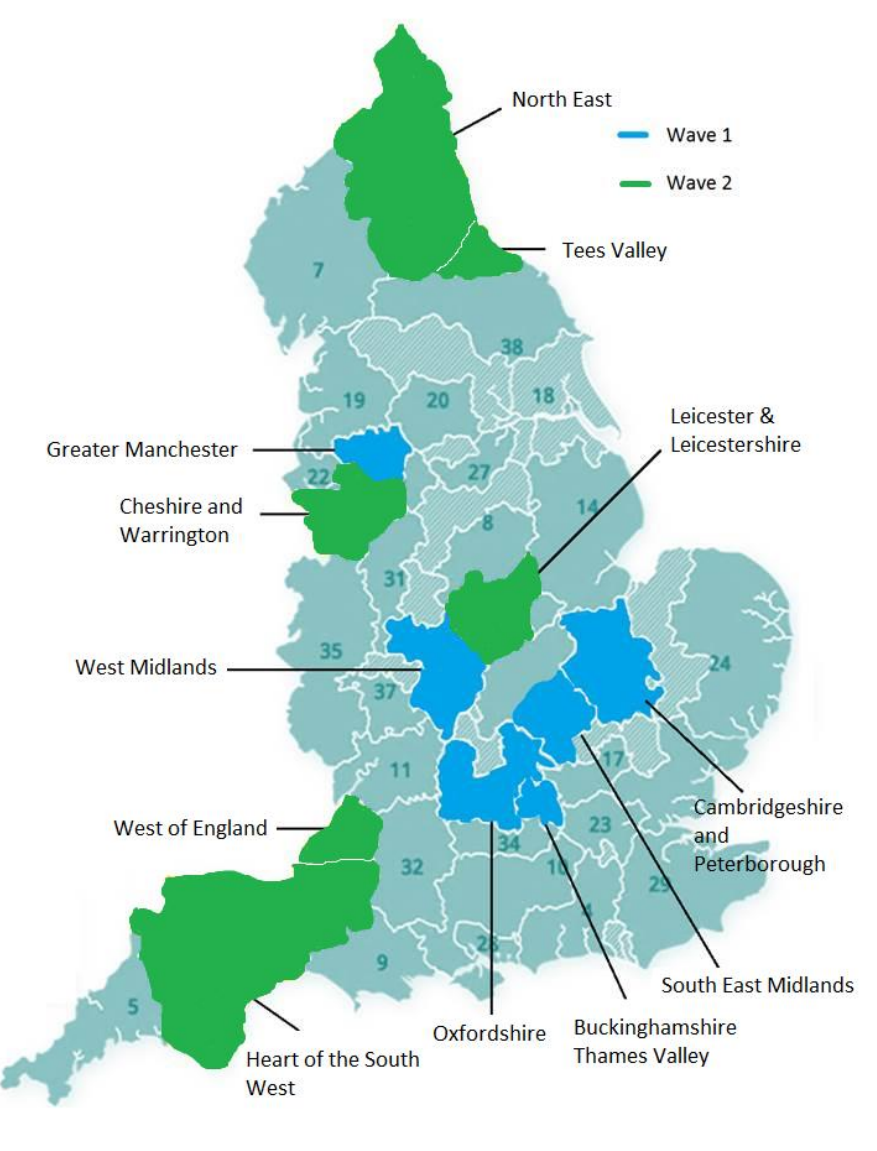

From a NW perspective, the region is generally not performing well against the HDT (Figure 2). No authority failed the test completely, though 13 of 39 Local Authorities fell below the 85% threshold in 2018, and should therefore produce an Action Plan (as well as apply a 20% buffer to their housing land supply).

Figure 2 Housing Delivery Test 2018: North-West Districts

Source: MHCLG / Lichfields

Based on analysis conducted by Planning Magazine

[2], of the 13 NW Councils requiring intervention, 4 authorities had not produced an Action Plan within 6 months as required by national policy (Warrington, Blackburn, Tameside and Rossendale)

[3]. Warrington in particular had not produced an Action Plan despite delivering just 55% of their LHN requirement.

On a national scale, of the 108 authorities required to produce an Action Plan, only 20% had managed to publish one by the August deadline. Considering the emphasis that the Government has placed on the HDT, this is a disappointing statistic, but one which should improve as Councils become more familiar with the process.

However, there appears to be no explicit sanction for failing to produce an Action Plan within the 6 month deadline (of the HDT’s publication). The Practice Guidance

[4] states that Councils are ‘expected’ to produce Action Plans. It is clear that Action Plans are not viewed as a punishment, but rather as a solution to under-delivery to redress poor performance. The question is, whether they contain ‘actions’ that will deliver any meaningful increase in housing delivery.

What do they contain?

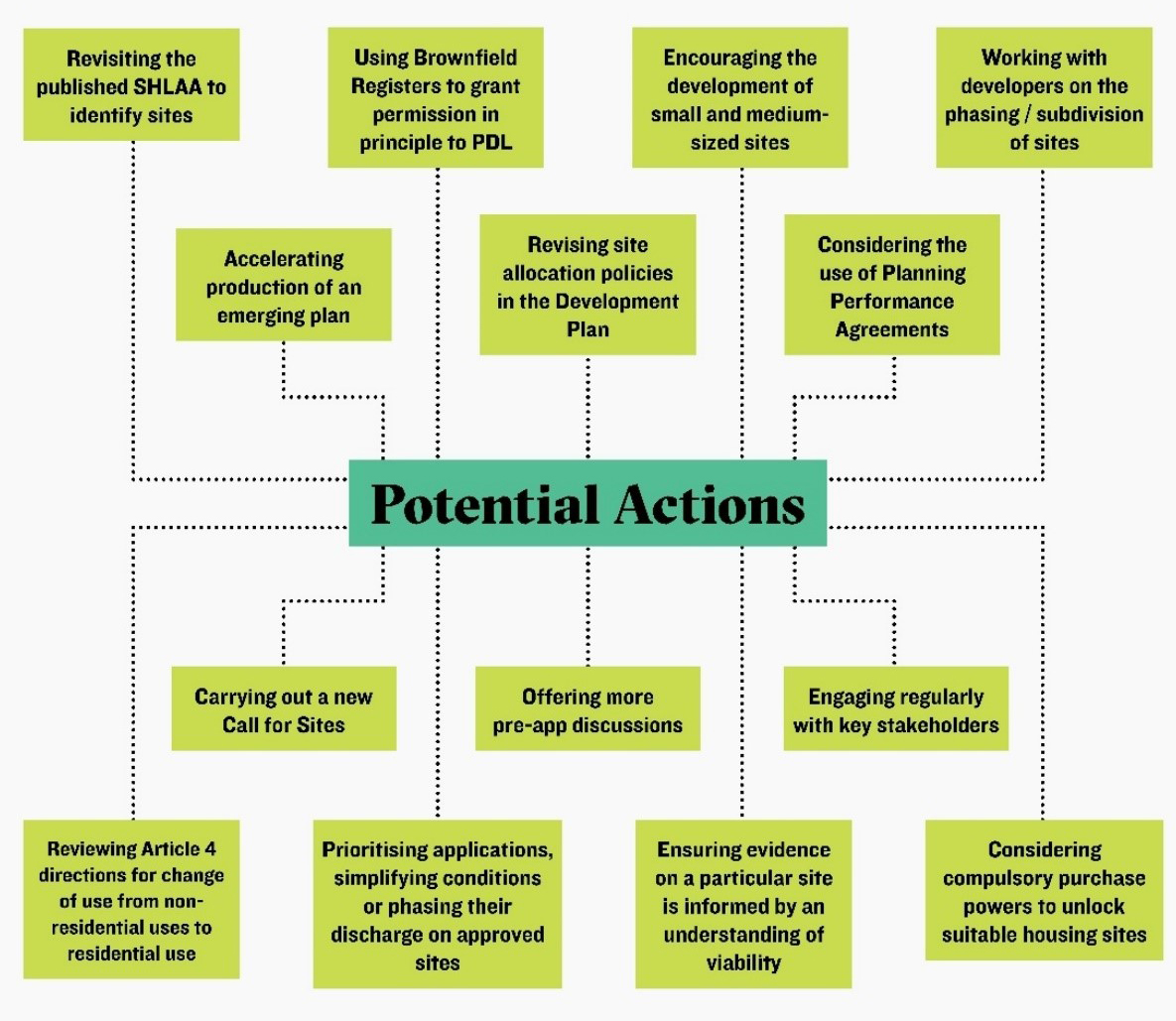

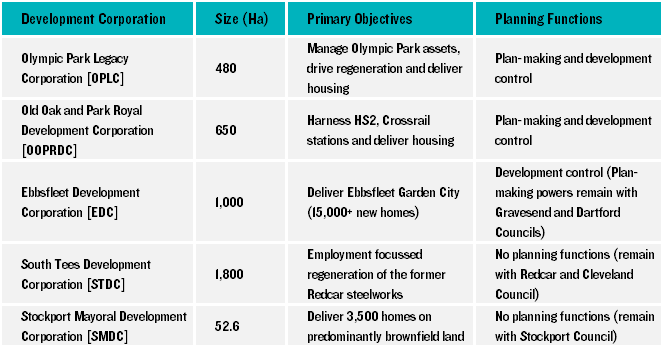

The Practice Guidance

[5] sets out a list of actions which Councils ‘could’ consider as part of an Action Plan (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Potential Actions

Source: Planning Practice Guidance

Based on the Planning Magazine

[6] analysis, which assessed the content of all published Action Plans across England and Wales, it becomes clear that many authorities have chosen the easier of these options. The majority of the actions do not provide any real bite, with many actions containing soft buzz words such as ‘encourage’, ‘promote’ and ‘consider’.

Analysis of the first group of nine Action Plans published across the NW reveals that actions such as ‘member training’, ‘shifting resources towards planning departments’ and ‘increased engagement with developers’ appear with regularity. Crucially, there appears to be limited provision for practical improvements to boost supply, such as committing to release safeguarded land or delivering infrastructure or funding to bring forward / unlock stalled sites.

There are some good initiatives being put forward, such as policy requirements to build at higher densities and developing small sites, though these have not been consistently proposed across the North West. The creation of Council-owned development arms provides another potentially helpful initiative, with numerous Councils citing this within their Action Plans. Though realistically, this could only have a meaningful effect in the longer-term, and is unlikely to be a short-term solution. So far, the requirement to produce an Action Plan appears to be a mechanism simply ‘encouraging’ Councils to boost delivery rather than ensuring meaningful solutions.

Where an Action Plan has yet to be produced, we may begin to see Inspectors using the absence of an Action Plan at appeal as further evidence in the planning balance for or against housing, if Councils are not engaging with the process or demonstrating a commitment to boost housing delivery. If Councils are unable to demonstrate the implementation of their Action Plan, then this could also weigh in favour of a proposal.

Moving Forward

In 2020 the HDT thresholds will increase further. Unless delivery significantly increases we could see a number of Councils across the NW failing the test and triggering the presumption in favour of sustainable development. Based on an initial analysis, there is limited evidence to suggest that Action Plans will provide the boost to delivery required to ensure the presumption in favour is not triggered.

This is particularly worrying for Greater Manchester, as well as the Liverpool City Region, both home to a number of significantly underperforming authorities.

A number of the Greater Manchester authorities are constrained by Green Belt, and this has certainly compounded the issue. The timely adoption of the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework [GMSF] is widely seen as the long-term solution to the sub-region’s persistent under-delivery. Adoption of the GMSF remains a crucial way of unlocking sites and boosting delivery. However, the latest delay rules out a further draft of the GMSF being published before next year’s Mayoral and local elections taking place in May 2020.

With a continuing absence of tangible, alternative solutions to addressing the under-delivery of housing, alongside a clear reluctance to release Green Belt, it is likely that related issues such as housing affordability will continue to intensify across the region.

The delivery of robust, practical Action Plans where required can, and should, act as a remedy to help prevent this. However, the lack of bite to the penalties imposed by the HDT, and the absence of any meaningful sanction for either non-conformity or lack of progress delivering the Action Plan, is a clear concern.

Conclusions

The HDT represents a key monitoring tool for the Government to incentivise local Councils to deliver the homes they need. However, it is clear that the Action Plan process may lack any real teeth, and it is disappointing that across the North West some Councils failed to produce an Action Plan within the deadline. Although we may see some implications for Councils at appeal, there appears to be no formal sanction for non-compliance.

This prompts the question - are Action Plans really providing the level of incentivisation that already underperforming authorities require in the North West?

It is clear that the overall Action Plan process needs significantly strengthening, with publication of an Action Plan perhaps becoming a requirement rather than an ‘expectation’, with associated penalties for non-compliance.

It may be too soon for this to happen before the next round of (delayed) HDT results, but a process of reinforcement should certainly be considered before the 2020 results are published in November next year.

[1] https://www.planningresource.co.uk/article/1665194/housing-delivery-test-results-shelved-until-general-election[2] https://www.planningresource.co.uk/article/1663026/read-council-by-council-guide-measures-taken-boost-housing-delivery[3] Warrington and Blackburn had responded to Planning Magazine to state they are in the process of preparing an Action Plan, though Tameside and Rossendale had not responded as of 7th October 2019.[4] Paragraph: 048 Reference ID: 68-048-20190722[5] Paragraph: 051 Reference ID: 68-051-20190722[6] https://offlinehbpl.hbpl.co.uk/NewsAttachments/RLP/CauseCitedTable.pdf