Last week the GLA adopted its

Purpose-built Student Accommodation (PBSA) London Plan Guidance (LPG) which builds upon London Plan Policy H15. This is a document which those of us working in the PBSA sector have been eagerly awaiting. It is intended to facilitate and shape the next generation of London’s PBSA schemes.

London is suffering from a structural undersupply of PBSA accommodation relative to the growing full time-student population in the capital. Supportive GLA guidance could play an instrumental role in addressing this need. We give our verdict here on the LPG and whether it will help or hinder future PBSA schemes in the capital.

The Role of PBSA in London

A common planning issue encountered on some PBSA projects involves evidencing the need for student housing and demonstrating how PBSA can contribute positively to London’s mixed and balanced communities.

The LPG recognises the shortfall in PBSA supply against London’s burgeoning student growth and identifies the role of well-designed and appropriately located PBSA in meeting a defined need. It acknowledges the role of PBSA in meeting housing need on a ratio of 2.5:1 (in line with the London Plan). The role of PBSA in meeting housing need is twofold: (i) directly providing accommodation for students; and, (ii) indirectly alleviating pressure on traditional rented homes/HMOs (which could otherwise provide family sized homes to the wider market). This is explicitly acknowledged within the LPG.

The LPG also helpfully recognises the role PBSA can play in strengthening the capital’s mixed and inclusive neighbourhoods; helping diversify housing stock and contributing positively to vibrancy and character. It provides guidance on how to maximise the positive effects of student housing schemes in the context of overarching London Plan objectives.

The guidance discusses the wider economic and regenerative benefits of PBSA. It continues to position PBSA development as an important contributor to London’s knowledge economy; leveraging high-quality student accommodation to attract domestic and international students and, in turn, reinforcing and strengthening London’s world-class higher education offer.

The LPG’s explicit recognition of the pressing need for new PBSA, its contribution towards housing targets, its role in delivering mixed and balanced communities and its economic/regenerative benefits are all positive facets of the LPG. The guidance provides constructive material to strengthen the ‘benefits case’ supporting PBSA development in the capital.

Spatial Distribution of PBSA

It is important that PBSA is appropriately located, though locational considerations should be applied with flexibility reflecting the nuances of individual schemes. The LPG encourages positive planning for PBSA; directing student housing developments towards well-connected locations including metropolitan and town centres, the CAZ, Inner London Opportunity Areas and centres with high or medium residential growth potential. Helpfully, it also acknowledges that PBSA can also be appropriate outside these areas, where sites are well connected to university campuses, in medium to high PTAL areas or in Outer London Opportunity Areas.

Overconcentration of PBSA

London’s universities are disproportionately concentrated in central and inner London, particularly within the CAZ. PBSA development has typically been clustered in such locations. The LPG acknowledges that local-level concerns can be encountered regarding the dominance of PBSA in such areas, both spatially and in delivery pipeline terms. In our view, the spatial agglomeration of centrally located PBSA is partly a logical function of the expectation in Policy H15 for nominations agreements linking student housing to local higher education provider (HEP) campuses. Indeed, despite advocating against over-concentration, the LPG does also recognise the value of such clustering as opposed to the dispersal of PBSA schemes in certain Outer London locations remote from HEPs.

London Plan Policy H15 does not itself reference overconcentration of PBSA; however, in our experience it can often be cited by communities as a concern. The LPG suggests measures to address perceived over-concentration of PBSA (and by association dilution of conventional housing) both in Local Plan policy and in decision making. The guidance suggests, for example, that LPAs could introduce ‘thresholds of concern’ (i.e. ratios of PBSA to conventional housing stock); encourage separation distances between parallel/ cumulative PBSA schemes; or identify PBSA bedspace caps within a defined area to restrict overconcentration.

In the interest of developing mixed and balanced communities across London, it is of course important that PBSA (or any other single housing product/typology) does not become singularly dominant in a neighbourhood; however, the LPG guidance could be seen to give LPA’s free reign to introduce rigid and restrictive PBSA policy to limit an area’s student housing development. The GLA has helpfully set out the evidence required to support such policies, but it will be incumbent on PBSA developers and professional teams to actively monitor emerging Local Plans and guidance documents to ensure such thresholds do not curtail and stifle otherwise acceptable and beneficial new PBSA development.

As an aside, the LPG also recognises that positive local PBSA policy can facilitate a balanced housing stock. It notes that boroughs with a shortage of family homes should look to include policy advocating PBSA in Local Plans, cognisant of the benefits PBSA stock provides in releasing larger HMOs, which are often occupied by student sharers, back to the stock of single family dwellings.

Lichfields recognises the importance of ensuring PBSA is appropriately located and does not dominate a neighbourhood; however, student housing plays a positive role in London’s communities, and it is rare that the proportion of PBSA will become so singularly dominant that it harms an area’s housing stock composition. In this context, it is critical that the LPG’s guidance on the spatial distribution and agglomeration of PBSA is implemented at the local level through well-evidenced policy or guidance, and that it is applied in a suitably flexible manner. It should not be allowed to unduly suppress otherwise acceptable PBSA developments and curtail their housing, economic and regenerative benefits.

Neighbourhood Integration

PBSA can contribute meaningfully to place-making and regeneration objectives through a well-considered mix of uses, design and management strategy that serves to activate and enliven London’s neighbourhoods. The LPG acknowledges that incorporating publicly accessible uses, such as shops, services and community facilities, and open space, alongside PBSA, can contribute towards place-making objectives and capture student spending locally. Similarly, employment floorspace, including affordable workspace and co-working accommodation can be beneficial.

At Lichfields, we are well versed in managing PBSA-led mixed use schemes and producing bespoke PBSA community integration strategies to address these criteria and effectively communicate the benefits of complementary mixed use development including PBSA – one recent example being Devonshire Place, Southwark.

Affordable Housing

London Plan Policy H15 states that boroughs should seek to ensure that the maximum level of PBSA is secured as affordable student accommodation (ASA). Such provision can unlock the GLA’s fast-track affordable housing route, at levels of 35% ASA (or 50% ASA on public or industrial land).

Notwithstanding this, the LPG acknowledges that the inclusion of conventional C3 housing alongside PBSA can be acceptable on larger sites, and is often desirable. The LPG suggests that such mixed use schemes can be acceptable on sites where C3 housing delivery is subdued and on sites where C3 permissions have not been built out. The guidance identifies a number of considerations relating to the provision of, and the prospective balance between, ASA and C3 affordable housing.

On this basis, the LPG does provide scope to introduce C3 housing alongside PBSA, though the priority affordable component remains ASA. Indeed, the guidance states “it will rarely be acceptable for ASA to be entirely replaced by C3 affordable housing”. From our experience in the sector, however, the delivery of PBSA can unlock affordable C3 housing in a way that is unattainable through conventional private housing led schemes. The proportionally greater value of PBSA can cross-fund conventional affordable housing, which presents a greater strategic housing need than ASA. Whilst there is clearly a need for both ASA and C3 affordable housing across London, and the more flexible approach to affordable housing advocated in the LPG is a positive step, we wonder whether the guidance could have done more to facilitate and promote conventional affordable homes alongside PBSA – the benefits of mixed tenure development has of course been acknowledged in the recently proposed amendments to the NPPF.

Finally on affordable housing, the LPG recognises that ASA is not eligible for CIL relief. To overcome this, the LPG suggests boroughs may wish to consider applying nil or reduced CIL rates compared to market PBSA. This is helpful, though will clearly only take effect when a LPA updates its CIL charging Schedule.

Design, Functionality and Accessible Student Accommodation

The LPG provides qualitative guidance on design quality, functionality and inclusivity. It does not set specific design standards for PBSA development. The decision to not quantify explicit standards is considered appropriate and provides suitable flexibility as the PBSA sector in London continues to rapidly evolve and innovate.

The LPG is helpful with respect to inclusive design and meeting the needs of disabled students. Notably, it adopts a pragmatic approach that reflects the underlying need for this specialist accommodation, reducing the conventional C3 requirement for 10% wheelchair accessible dwellings (London Plan Policy D7) to 5% wheelchair accessible PBSA units, plus 5% adaptable accommodation. The GLA’s Wheelchair Accessible Student Accommodation Practice Note has been withdrawn in parallel; it is now superseded by the adoption of the LPG.

Nominations Agreements

London Plan Policy H15 seeks to align PBSA provision with established need through the use of nominations agreements. The agreements establish the right of the signatory HEP to allocate students to a majority proportion of PBSA bedspaces within a development (including all ASA). Nominations agreements have historically been rigidly imposed, though certain boroughs are now applying greater flexibility, particularly where PBSA schemes are delivering wider benefits (notably affordable housing) or where a development is not directly connected to, or in the immediate vicinity of, a single HEP.

There can, however, be a tension between the requirement for nominations agreements which direct development to specific locations surrounding HEPs and local concerns relating to overconcentration of student schemes. Will the LPG’s continued insistence on nominations agreements accentuate this tension and limit otherwise acceptable PBSA schemes that are more remote from HEPs?

From our own experience, HEPs are often cautious when entering into nominations agreements due to the commercial liabilities involved, with a low appetite for financial risk resulting in nominations agreements being increasingly challenging to secure.

The LPG does provide some flexibility around nominations agreements. It encourages s106 obligations to require ‘reasonable endeavours’ to secure nominations agreements covering the majority of student bedspaces, including all ASA (i.e. over 50% of net bedspaces). The LPG provides clear guidance on what is meant by ‘reasonable endeavours’ and how this can be evidenced. This includes details of constructive engagement, timelines, accommodation strategies and any suitable proxies.

In the event that a nominations agreement cannot be secured, the LPG allows for a fallback cascade mechanism of direct lets to be secured via the S106. Where applicable, this would apply to all unlet and un-nominated market rate bedspaces. Nominations agreements can also contain cascade mechanisms that could be invoked if a HEP is not able to nominate all allocated bedspaces by the end of the summer holiday period (by 31 August). Such a mechanism will enable HEPs to manage the risk of any unforeseen demand downturns.

In the absence of a nomination’s agreement for ASA, the LPG also clarifies that (as a last resort) the fallback position would be for the provider to allocate according to need, with an appropriate audit trail of the allocation strategy to be provided to the LPA on request.

Further guidance is also provided in the LPG on how best to evidence interest and discussion from HEPs during pre-application engagement on projects. For example, the guidance discusses how ‘letters of comfort’ and evidence that a PBSA scheme meets an institution’s requirements can assist in pre-application discussions and encourage LPAs to support the principle of PBSA.

Finally, the LPG provides guidance on a new process for applying to become an approved proxy for nominations agreement purposes. This will apply to charitable organisations and other collectives. We envisage such proxy engagement will be most beneficial for smaller schemes, essentially brokering the nominations process to lessen the disproportionate administrative burden encountered by smaller developments in securing such agreements. The GLA has prepared a

document covering process and eligibility criteria for proxy organisations and collectives.

The LPG’s additional clarity and detail on nominations agreements is certainly helpful. However, we do feel that it misses an opportunity to endorse greater flexibility in the application of nominations agreements to ensure development is not stymied. The guidance could have encouraged nominations agreements in appropriate circumstances in London, whilst also allowing a greater proportion of PBSA schemes without nominations agreements, perhaps where locational considerations support a more open approach to direct lets and/or to incentivise the delivery of wider planning benefits, including mixed tenure developments and C3 affordable housing on site.

Summary

In summary, London is facing a pressing need for well designed, effectively managed and suitably located PBSA accommodation. The latest generation of PBSA schemes have an important role to play in meeting an evidenced housing need, strengthening mixed communities and supporting London’s knowledge economy and globally renowned HE offer. The need for PBSA in London is greater than supply and the planning system has an important role to play in fostering and facilitating new PBSA schemes.

The GLA’s new PBSA LPG helpfully recognises this need and acknowledges the benefits that can be generated by PBSA schemes. Many aspects of the LPG are logical and helpful, providing clarity and detail to assist in the practical application of London Plan Policy H15. For instance, the guidance actively supports PBSA schemes in the right location and recognises the economic and regenerative benefits of student housing. It highlights the place-making attributes of PBSA and its prospective role in developing vibrant, mixed and sustainable communities across the capital. It strikes the right balance between clarity and flexibility in terms of design measures and accessible units. The LPG also includes some constructive guidance on the scope for mixed use schemes combining PBSA and affordable housing, and it provides further detail on the application of nominations agreement.

There are, however, some elements of the LPG which remain overly restrictive and certain aspects which could be more progressive. The measures suggested to address perceived over-concentration of PBSA in an area could, for example, give LPA’s ammunition to rigidly inhibit otherwise acceptable PBSA schemes. Similarly, given the opportunities for PBSA to unlock other uses and benefits for example C3 affordable housing delivery, the guidance could have done more to facilitate mixed tenure sites and conventional affordable homes alongside PBSA. We also feel that the LPG misses an opportunity to endorse more flexible approaches to nominations agreements in the right circumstances.

Perhaps these are points which could be addressed in the forthcoming new London Plan, but until then it is important to remember that the LPG is guidance, not policy or law, so is not a strict rulebook but should be treated as a material consideration in the planning process.

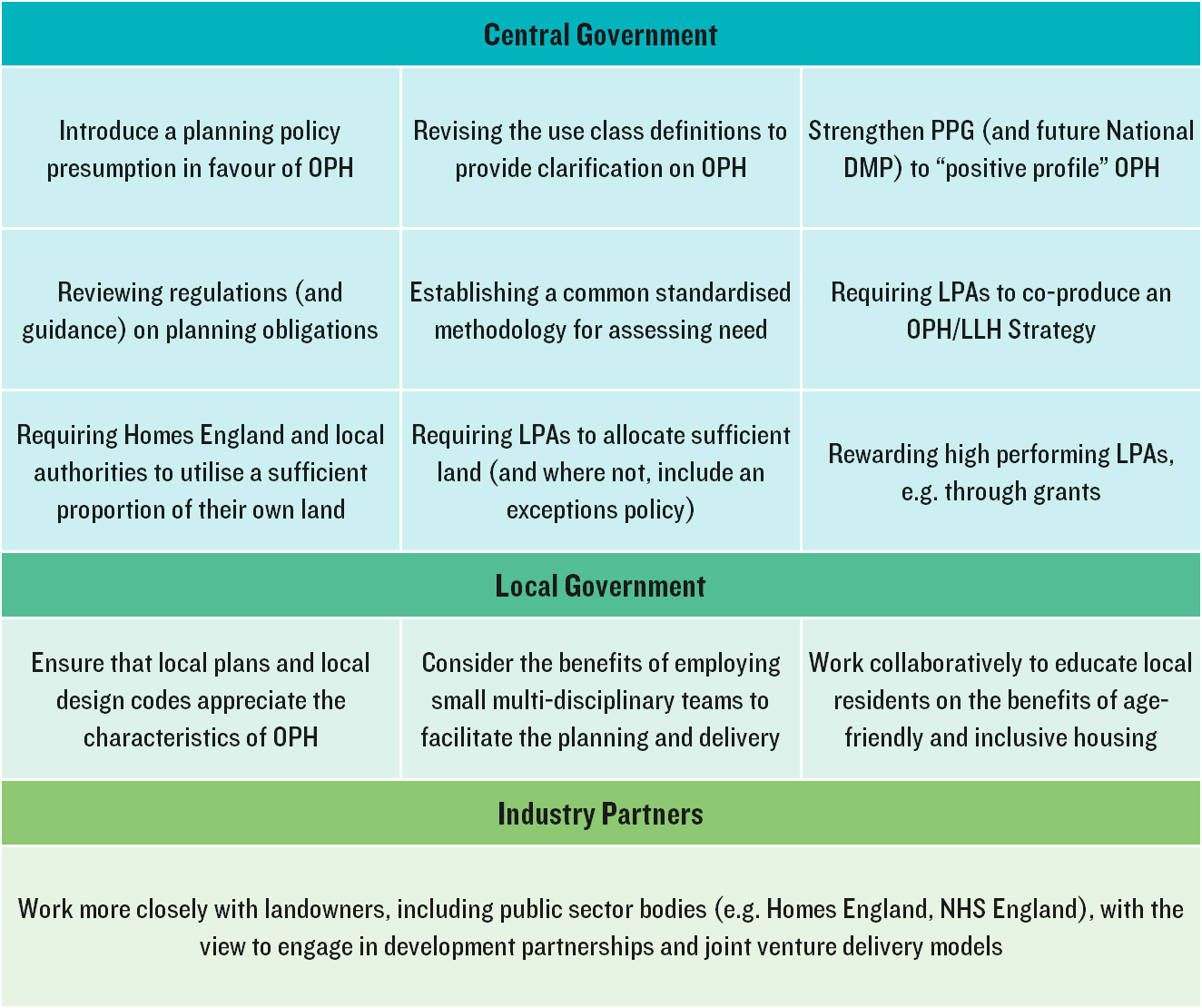

Source: Lichfields Analysis

Source: Lichfields Analysis