In recent years, London has seen a surge in Co-living, Build-to-Rent, and Purpose-Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) developments. But what exactly are these housing types, and how do they differ from traditional shared rooms in Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs)? In this blog, I will explore the key differences between these new urban living products and conventional HMOs, highlighting their benefits and role in London’s housing market —from offering tenants relatively affordable, high-quality living experiences, to easing pressures of the housing market and creating new development opportunities in suitable locations.

Finding good-quality accommodation to rent in London is a significant challenge for recent graduates like myself, and many young professionals starting their careers in the city. As a student studying in London, I’ve experienced the convenience and reliability that student accommodation can bring. A professional management company ensured that any issues, such as a faulty boiler or broken appliances, can be resolved promptly, often by the next day. Communal spaces like hallways, lifts, and shared amenities such as kitchens and lounges were consistently well-maintained, thanks to regular visits from professional maintenance team.

However, after graduating and moving into the private rental market, I quickly discovered that high quality management is not always guaranteed. Unlike professionally managed student housing, HMOs are not always maintained to the same high standards. For instance, a faulty boiler might take a week to be repaired. Shared spaces are often minimal because landlords convert living rooms into additional bedrooms to maximise rental income. These communal areas are frequently neglected, sometimes left untidy or unclean by other tenants, with little to no intervention from the landlord.

What I experienced was not an isolated incident. Data from the English Housing Survey (2021–2022)

[1] revealed that 23% of private rental properties in England fail to meet the Decent Homes Standard. This standard requires a property to be in a reasonable state of repair, offer modern facilities, and provide a reasonable degree of thermal comfort. The situation is particularly severe in HMOs, given that landlords are often reluctant to invest in maintenance, as HMOs tend to incur higher upkeep costs by wear and tear than traditional buy-to-let properties due to a higher number of occupants.

Living rooms in shared houses could also be converted into additional bedrooms, and in some cases, multiple occupants share a single bedroom in order to reduce their rental costs. This significantly reduces the availability of shared amenities, creating cramped and uncomfortable living conditions. An article by the Guardian

[2] highlighted that as many as 11 people could be living in a four-bedroom house. Analysts estimate that there are at least 32,000 hidden large-scale HMOs across the country, underscoring the widespread nature of the problem.

Furthermore, many HMO properties are often created as a result of repurposing existing family homes, decreasing the available family homes in an area. News reports

[3] have shown that in certain highly sought-after areas in London, entire streets have been converted into HMO properties, causing serious concerns among existing household residents about noise pollution, waste disposal, and insufficient parking spaces, and ultimately, leading to fewer large properties being able for families to rent or buy.

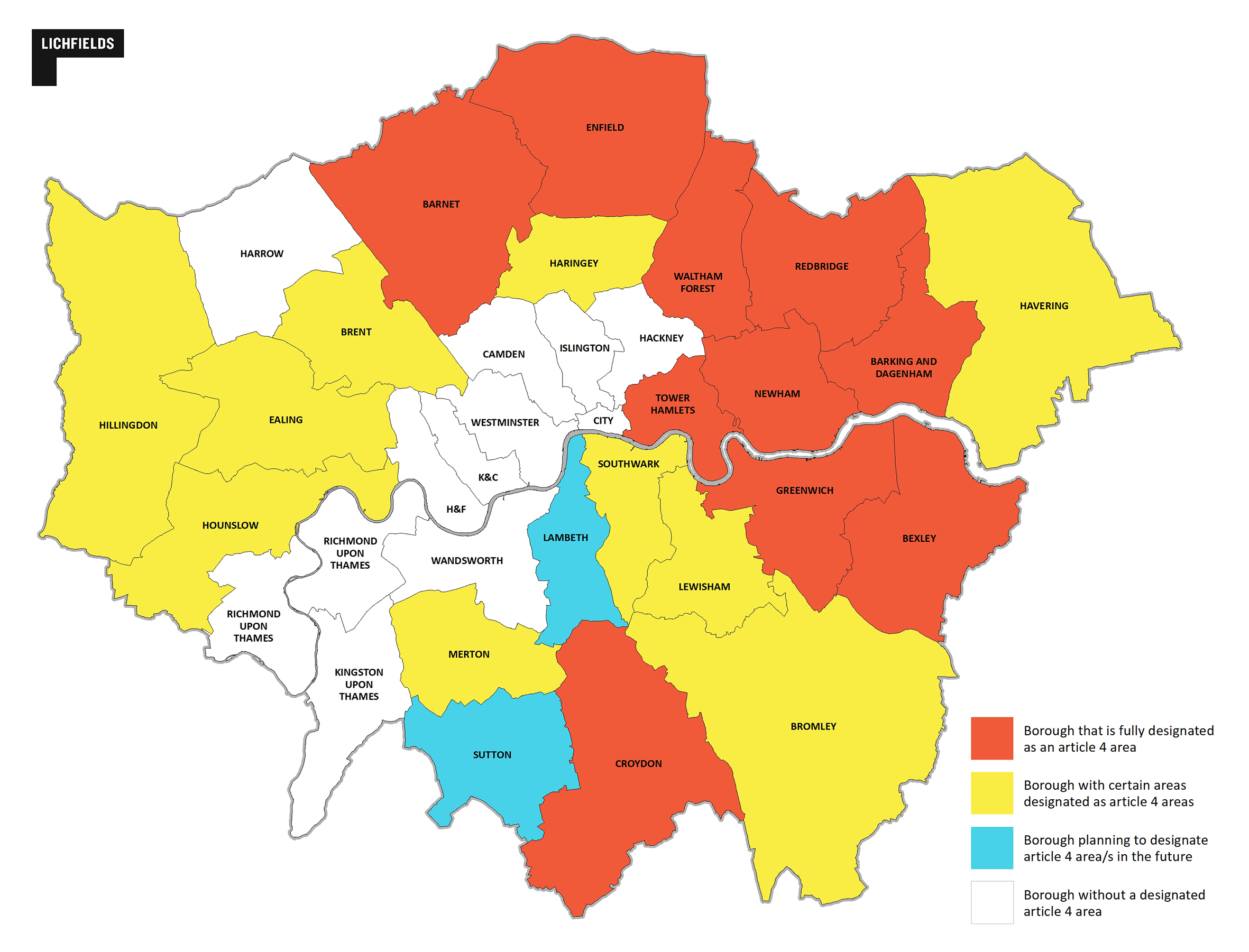

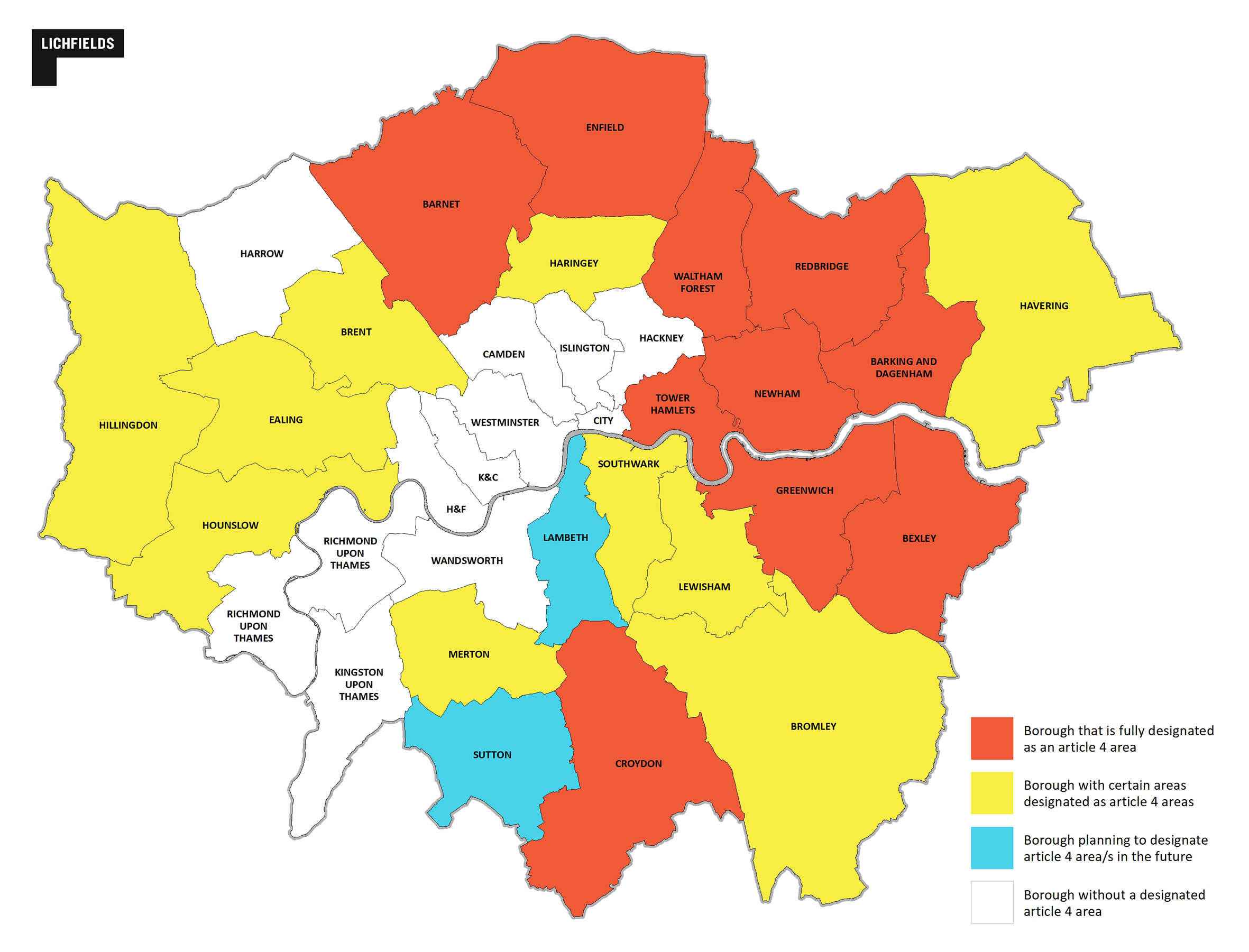

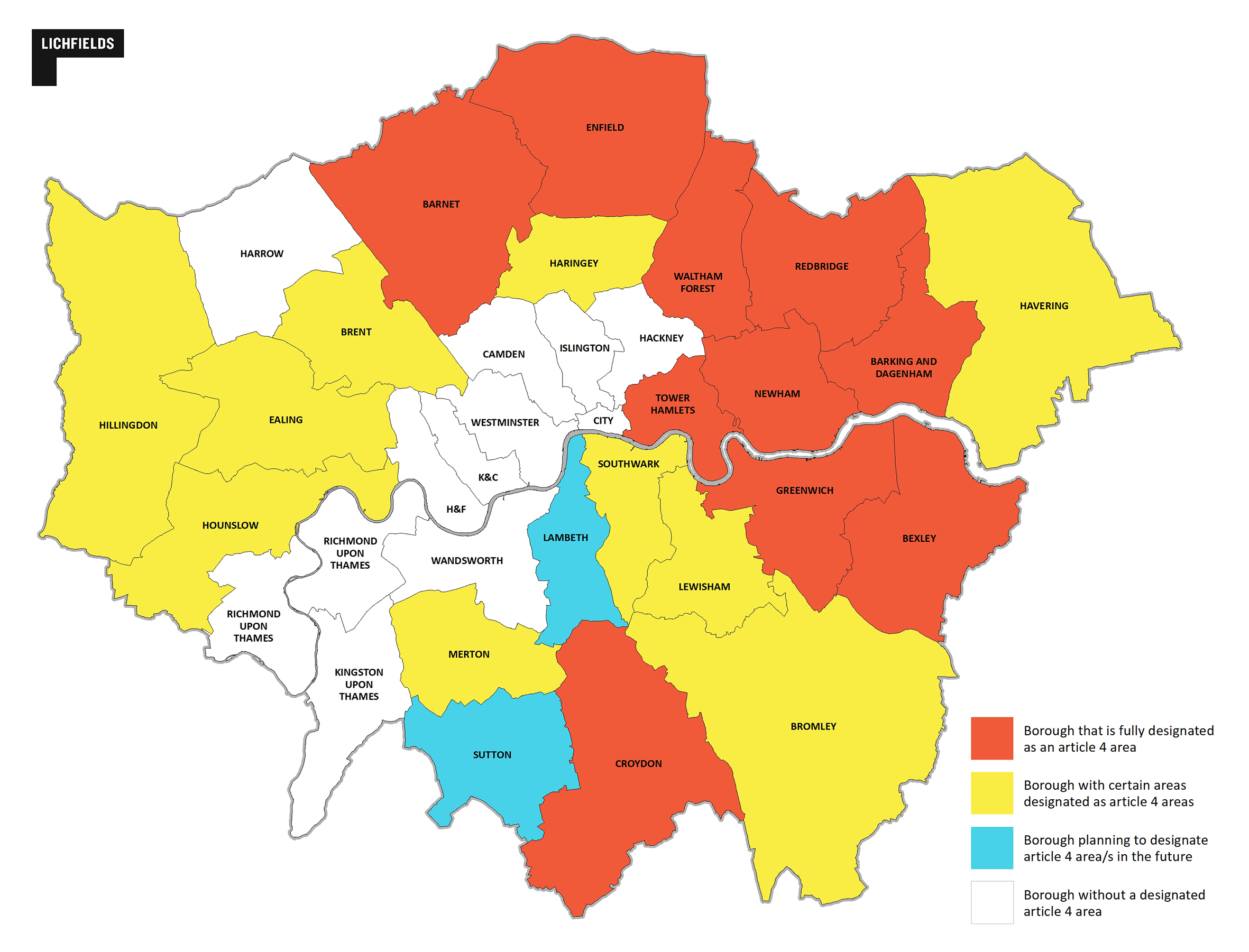

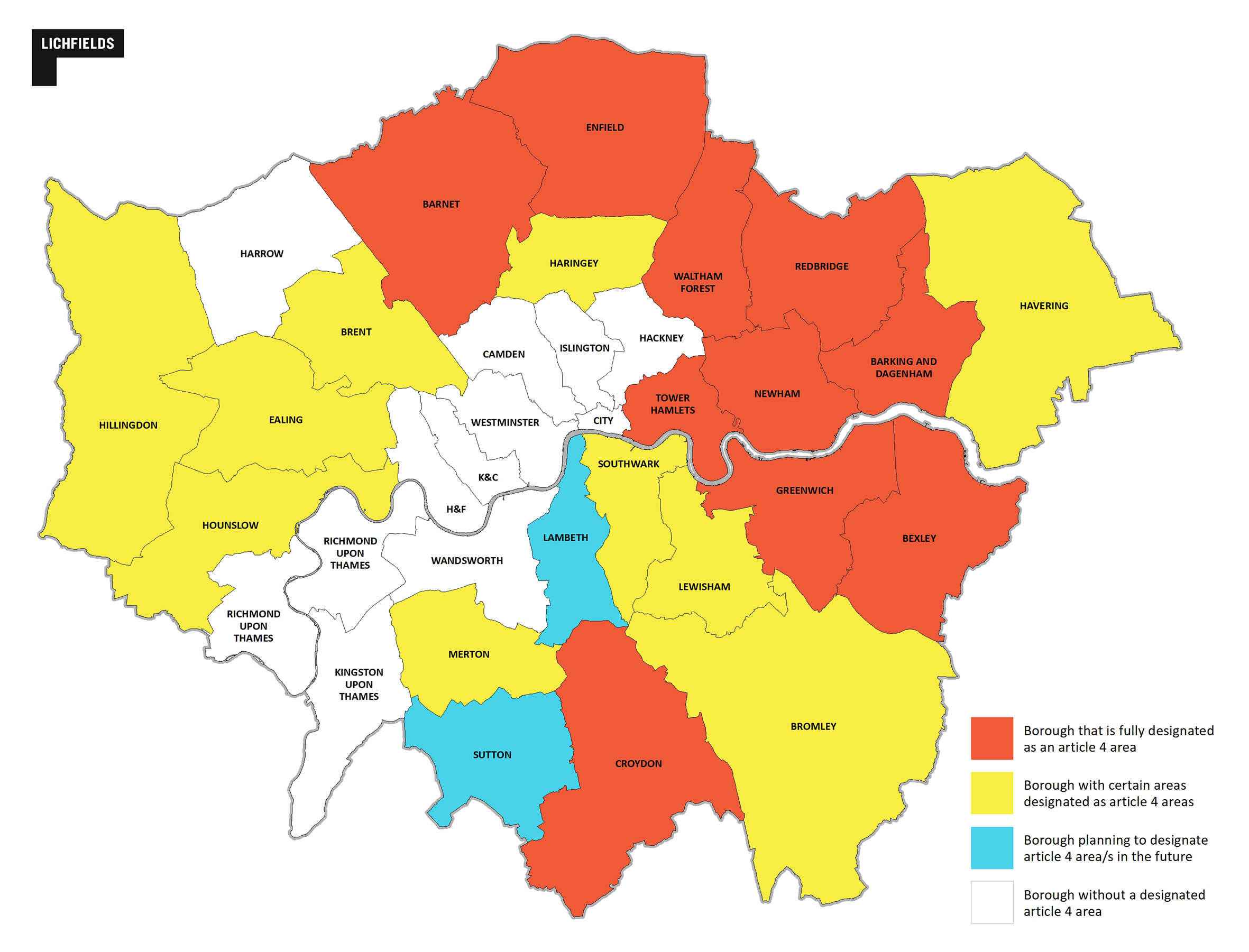

To manage and restrict the growth of low-quality HMO accommodation, many councils in London have enacted Article 4 directions, removing the permitted development rights of converting conventional housing (use class C3) into HMO housing (use class C4) under Permitted Development Rights Class L. As in London today, many boroughs have fully/partially adopted article 4 directions to restrict this conversion:

Figure 1 Status of Article 4 directions in London Boroughs that restrict the conversion from use class C3 to C4 housing.

Despite the poor quality of accommodation in some HMOs, demand for these properties remains high due to their relative affordability. Data

[4] from the room-rental platform SpareRoom shows that as of March 2025, an average of 3.1 individuals are competing for a room to rent in London. Some boroughs like Barnet and Kingston Upon Thames have seen 12.6 and 8.5 persons competing for a room respectively, highlighting the significant mismatch between supply and demand. This stark imbalance demonstrates that there is a significant need for good quality rented accommodation, and the restriction of HMOs through Article 4 directions cannot be the sole solution to addressing issues of low-quality and poorly managed accommodation in London. A more comprehensive, alternative approach needs to be in place to balance between the objectives of providing more housing supply, while upholding the quality and standard of housing in London.

Co-living, Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) and Build-to-Rent

As the above demonstrates, there is an acute need to provide a diverse range of high quality housing options alongside HMOs in order to better meet the housing needs in the capital. Over the past decade, London has been at the forefront in the country for providing alternative urban living products, including Co-living, Purpose-Built Student Accommodation (PBSA), and Build to Rent developments. Many London boroughs are actively supporting these residential typologies, introducing broadly supportive planning policies designed to encourage their growth and guide appropriate delivery, as highlighted in our recent research and commentary on

Co-living,

Build to Rent and

PBSA.

A key differentiator of these alternative urban living products from HMOs is that they operate under unified ownership (a planning policy requirement) and benefit from professional on-site management. This offers advantages over traditional rental properties and HMOs, including greater tenancy security and flexibility—ensuring tenants are not forced to leave on short notice, and enhanced protection against risk of crime. Importantly, these urban living products help alleviate the demand on HMOs, thereby reducing the conversion of family homes and preserving much-needed housing for families.

For developers, these urban living products present a valuable investment opportunity if they are being developed in suitable locations, especially in well-connected locations with supportive policies and Article 4 restrictions on HMO conversions, reducing the reliance of low-quality HMO accommodation in the rental market. These typologies can also contribute to the creation of mixed and balanced communities through the communal facilities that is provided, fostering social interaction, thereby enhancing the overall well-being of local residents.

Co-living

As explored in Lichfields’ recently published

Insight Focus, Co-living is a type of living product that provides individual rooms with a size from 18-27 square metres

[5]. The development would provide a range of dedicated facilities, supplemented by a range of high quality communal facilities throughout the building which residents are encouraged to use, including large shared kitchens, various living, dining and working spaces, and often gyms, games rooms and cinema rooms. Unlike rental properties in the Private Rented sector (PRS), all units fall under a unified ownership, providing on-site professional management. These features make co-living appealing to a wide range of people from different ages, including those who are new to London and may be unfamiliar with renting in the city, people going through a change in circumstance or those looking to meet other people in a safe and managed environment as discussed below.

The rental price of Co-living units includes council tax, utilities, WiFi, and typically access to these communal facilities such as co-working spaces and gyms. When factoring in these amenities, Co-living units can be up to 20% cheaper

[6] than comparable studio flats or flat shares in the same area. This makes them a cost-effective option while maintaining high-quality living standards and security.

In planning terms, Co-living developments fall under the Sui Generis use class, distinguishing them from HMOs. Within London, Co-living schemes are subject to specific planning policy requirements set out under London Plan Policy H16 (Large-scale purpose-built shared living). These include locational criteria in well-connected areas, minimum space standards, room sizes, external spaces, cycle parking, and inclusive building design.

Co-living can play a significant role in expanding housing supply in the capital. This is acknowledged by the Large-scale Purpose-built Shared Living LPG (LPBSL LPG), which equates 1.8 co-living units to 1 home

[7].

Contrary to the common perception that co-living is primarily for young professionals and recent graduates, their appeal can attract a broad demographic. According to the research by Harris Associates

[8], the average age of a Co-living resident is 28, with over a quarter of residents aged 35 or older. The report also identified the main attractions of Co-living schemes as the convenience of all-inclusive bills (mentioned by 47.7% of survey respondents), opportunities for social interaction (21.5% of respondents), and flexible contract terms (12.3% of respondents). As such, rather than creating a demographic imbalance, co-living supports a diverse and well-balanced population in the areas where they are built.

Moreover, Co-living developments can play a key role in addressing London’s affordable housing needs. The higher values that these schemes can attract allows for cross-subsidisation that supports the delivery of much-needed affordable homes either on site or through a payment in lieu.

It is no wonder that the development of Co-living schemes are highly regarded and supported by the GLA and the LPBSL LPG, which highlights the critical role that Co-living plays in addressing the acute housing shortage in the capital and actively supporting future developments.

Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA)

Purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) developments are designed specifically to meet the needs of students, offering a variety of communal spaces such as large shared kitchens, living and dining areas, and study spaces, where students can both work and socialise. Similar to co-living developments, PBSA falls under the Sui Generis use class and is subject to a range of planning policy requirements outlined under London Plan Policy H15 (Purpose-built student accommodation) and the PBSA LPG (October 2024). This document includes detailed guidance on location in well-connected areas, design standards, management practices, affordable housing provisions, and nomination(??) agreement requirements.

With the UK student population reaching a record 2.27 million in 2021/22

[9] and is continuing to grow, increasing the availability of high-quality, high-density student accommodation is crucial. PBSA developments help alleviate pressure on the wider housing market, particularly for non-student renters, and contribute to preserving family housing by reducing the demand for HMO conversions.

The PBSA LPG supports the development of PBSA developments in appropriate locations, recognising the importance that PBSA play in providing accommodation for the needs for the rapidly growing student population and alleviating the pressure on the private rented sector and HMOs. Key points and analysis of the PBSA LPG can be found in this Lichfields’

commentary.

Build to Rent

Build-to-Rent developments provide a large supply of rental properties within a single development, offering comparable levels of affordability to the Private Rented Sector across all household types, significantly addressing the imbalance between supply and demand in the rental market. Unlike typical Private rented sector housing, Build-to-Rent developments need to comply with the policy requirements outlined in Policy H11 (Build to Rent), which includes unified ownership and on-site professional management. Additionally, these developments often offer communal amenities, enhancing the overall living experience for residents.

Although not specifically designed as a shared living product, according to the latest research on Build to Rent by the British Property Federation (BPF), Build-to-Rent properties are more likely have attracted a higher proportion of couples and sharers, with 59% of tenants fitting this demographic compared to 41% in the private rented sector

[10]. Moreover, Build-to-Rent housing is relatively more affordable, with tenants spending a lower average percentage of their gross household income on rent compared to those in the wider private rented sector, providing a more accessible and higher-quality alternative.

Summary

In my view, expanding the range of urban living options —is crucial to tackling London’s acute rental housing shortage. These types of living products can significantly increase the supply of high-quality rental homes, reducing reliance on often substandard and poorly managed HMOs. In turn, this shift allows HMOs to be reconverted into family homes, restoring them to their original purpose-built use.

In my role at Lichfields, I hope to contribute to bringing forward schemes which will genuinely contribute to easing housing pressures in the capital. Lichfields possesses extensive experience in securing permission for various types of Urban Living products in London and throughout the UK. We have been actively advising on many of London’s largest and most high profile co-living, PBSA and BtR developments, gaining unmatched expertise in the planning matters common to these urban living products in the capital. Our work has given us a strong understanding of relevant policies and the unique political dynamics of each borough.

For a more detailed analysis of Build to Rent, Co-Living, and PBSA please see our recently published Insights and commentary, and don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Footnotes

[1] One in four private rentals in England fail to meet decent home standards (The Guardian)

[2] ‘There’s no space’: rogue landlords double income by ignoring overcrowding rules (The Guardian)

[3] Residents of St Barnabas Road, Woodford Green, say HMOs are holding their 'whole street hostage' (The Guardian Series)

[4] Too many renters, not enough rooms in Smethwick, Solihull and Stockport (Spareroom)

[5] Large-scale purpose-built shared living London Plan Guidance - Feb 24

[6] The True Cost of Co-Living in London (Folk Co-living)

[7] Large-scale purpose-built shared living London Plan Guidance - Feb 24

[8] Co-living REPORT (Harriet Associates)

[9] Purpose-Built Student Accommodation: More than bricks and mortar (British Property Federation, 2024)

[10] Who lives in Build-to-Rent? (British Property Federation, 2024)