With the stroke of the prime minister's pen at the bottom of a letter to the President of the European Council, Article 50 of the Lisbon treaty was formally enacted and the curve of British history was changed forever. In spite of all of the discussion of what lies ahead, very little is known for sure: when the terms of negotiation are up for negotiation, certainty remains thin on the ground.

Given its relative economic position, and reliance upon £680m of EU funding each year, the potential impact of Brexit upon Wales may be even more significant than upon the rest of the UK. Many questions are being asked about what will happen, with a common theme relating to the impact upon housing need. It has been said many times since June that national sovereignty and migration were central to the outcome of the referendum. The follow-on argument is that a reduction in migration will result in a need for fewer new homes to be built.

The recent release of a new set of Welsh Government household projections provides a timely opportunity to revisit the merits of this argument. Through a careful consideration of this data, and the population projections that underpin it, some conclusions can be drawn.

The main focus of the discussion about the impact of Brexit upon population growth and housing need appears to have focused upon in-migration. The assumption being that greater controls on in-migration will result in a reduction in the number of people that move into this country, resulting in a consequential reduction in housing need. This perspective entirely overlooks out-migration. In order to fully understand the impact of Brexit upon population change in the UK, we must therefore focus on net migration (the difference between the number of people moving in from overseas and the number leaving the UK).

The 2014-based Welsh Government projections anticipate that net international migration will amount to 3,315 people each year (14,100 in, 10,800 out). This is 28% lower than the net international migration level projected by the 2011-based population projections, a significant change that is likely to have been influenced by a number of issues, including changing international migration patterns during the recession (which affected Wales slightly later than the rest of the UK). The split between EU and non-EU international migration is 49:51, so on this basis, the EU component would represent a net in-flow of 1,690 people per year. This equates to just 1% of net EU migration into the UK. Given that net migration to Wales from the EU is already projected to be very low compared to past projections and as a proportion of net EU migration to the UK, the scale (and impact) of any further change may well be limited. As explained below, this is particularly the case given the expected reduction in out-migration to the EU.

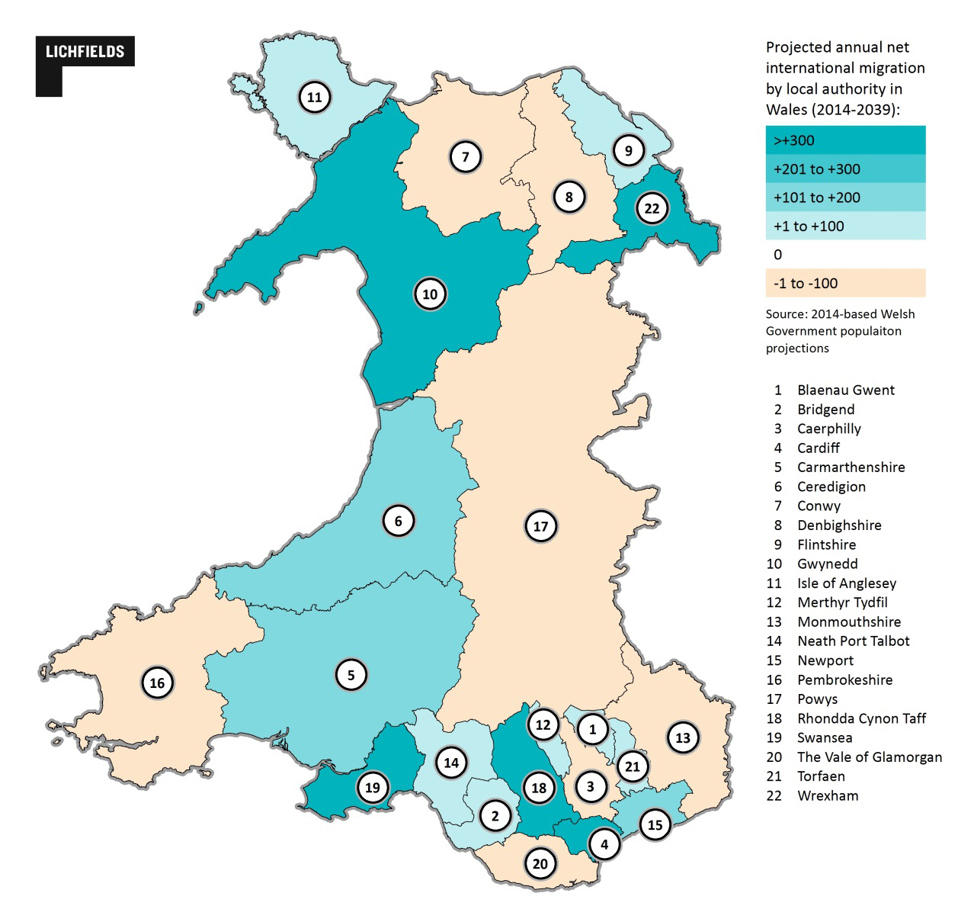

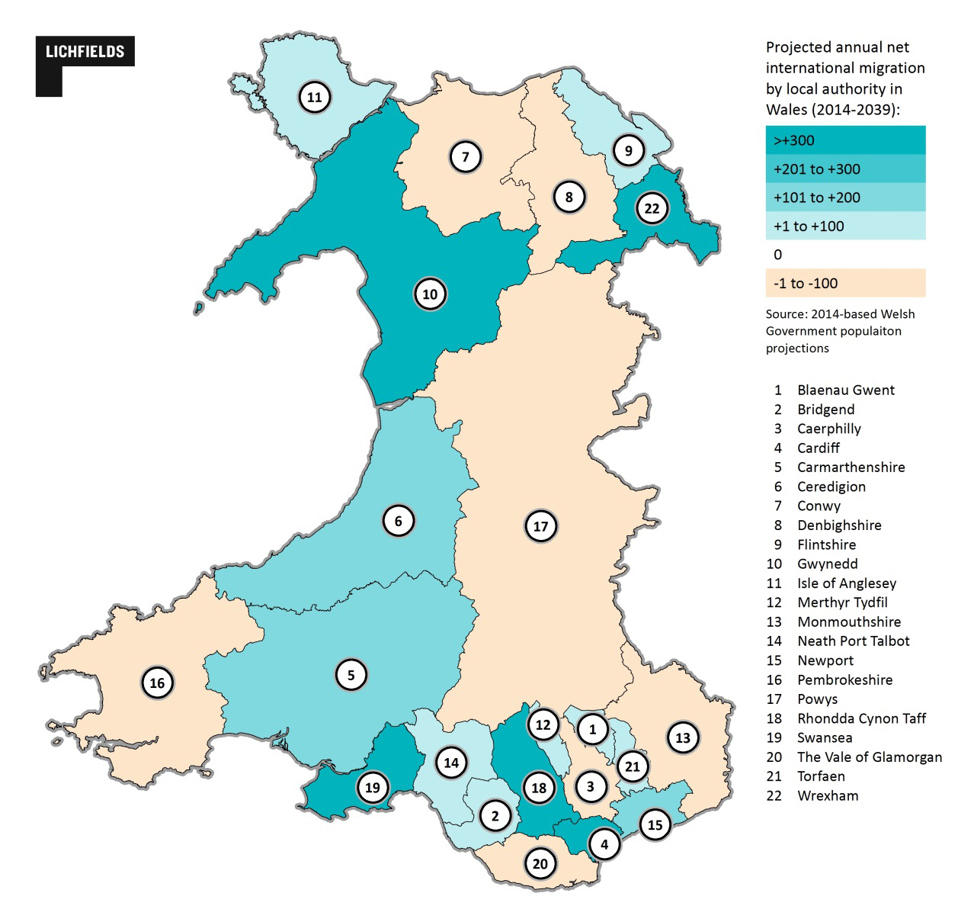

As one would expect, the picture across Wales varies markedly with Cardiff, Swansea, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wrexham and Gwynedd expected to account for 87% of net international migration to Wales (2,970 people). By contrast, seven authorities (Conwy, Denbighshire, Powys Pembrokeshire, Monmouthshire, Vale of Glamorgan and Caerphilly) are projected to have net international out-migration of 380 persons per annum.

Not only will any potential effect of Brexit upon net migration and overall population levels vary between different local authorities, the projections already anticipate a very different spatial distribution of international migration. This would have already informed the household projections and will continue to do so. Whilst the larger urban centres attract more net migration and are expected to see the highest level of household growth, there is not a direct correlation between the level of expected household growth in each local authority in Wales and the expected level of net migration. This is demonstrated by the fact that, with the exception of Powys, all local authorities in Wales are expected to experience household growth between 2014 and 2039, including those that are projected to have net out international migration. International migration is – and will remain – just one factor that impacts upon household change, alongside domestic migration, natural change, demographic profile and household formation rates are more significant in shaping household change in Wales.

The issue of demographic structure is also relevant when one considers the potential impact of Brexit upon out-migration. If greater controls are to be placed upon EU citizens moving into the UK, there might also be a similar increase in barriers to British citizens moving abroad. It is estimated that between ¼ and 1/3 of British migrants living in other EU counties are retired and there is no reason to believe that the proportion of people migrating from Wales for retirement purposes is any different to the national average. In addition to potential imposition of entry requirements (potentially relating to economic activity and employment), future restrictions in access to healthcare and pension payments might also deter people retiring in Europe.

The latest population projections show that, compared to a 5.1% increase in total population, the number of people aged 65 and over in Wales is expected to increase by over 42% between 2014 and 2039. If the future level of out-migration was to fall then the number of older people living in Wales would be expected to increase. The latest household projections show that older people tend to live in smaller households (commonly single person households or as couples) whilst younger people live in larger households.

Immigration from the EU will continue, just as it does from the rest of the world and the biggest controls are likely to be placed upon younger people that might not have a job to go to. The projections show that. The effect of this might therefore be to exacerbate the existing trend towards an ageing population. The result of fewer people living in larger households but more people living in smaller households will clearly not be a justification for a reduction in housing need. An increase in the number of older people will equate to a need for more homes. Arguments that we will need fewer homes are misguided. In the absence of any robust evidence to the contrary, we should continue with what we have and rely upon the latest Welsh Government household projections as the starting point of our determination of future housing need.