Even with the most meaningful of public exhibitions, having a say in what your city or neighbourhood should be like can often feel like a complex and time-consuming process.

Recognising that community engagement has the propensity to also be dominated by those with the loudest voices, many applicants are looking at a new wave of digital tools to help make the consultation process a more interactive and inclusive one. Capitalising on the smartphone era, a range of new technological advances are being made within the community engagement space – with mobile apps leading the way.

It is fair to say that in the UK, the procedural logistics of notifying local communities of forthcoming new developments have remained rather similar since the system’s invention with the

[1]. Today, it can be the case that one of the first encounters local communities have with proposals in their neighbourhoods come in the form of a piece of A public notice fixed to a lamp post. Interested local residents must then navigate developers’ or local authority websites, sifting through often a multitude of documents, such as planning statements, technical drawings, and design and access statements (that are themselves often divided into multiple files) before forming an opinion and commenting on a proposed development.

Apps, modelled on gaming and dating applications, are increasingly being employed as a means of making the planning process more transparent, as well as allowing local residents to register their support for, or objections to proposals in their neighbourhood, more easily.

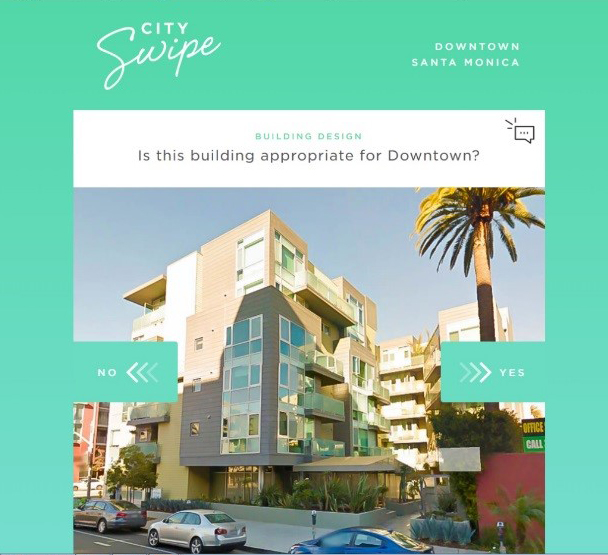

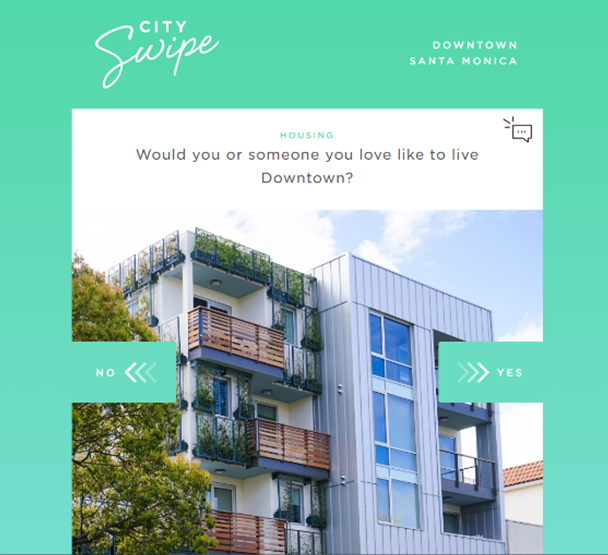

In Santa Monica, California, for example, the app

CitySwipe provides local residents with images of potential development scenarios – from street furniture and parking, to murals and market stalls. With simple “yes or no” questions being asked, residents are encouraged to swipe through and select their preferred options, accordingly. The Cityswipe engagement strategy runs alongside the usual formal City Council online survey as an additional way of shaping the emerging community plan and understand the local community’s aspirations for the area. The app is also used to reduce City Council costs of producing development notices in local papers and sending consultation letters.

Downtown Santa Monica City Swipe App (Source: dtsmcityswipe.com)

Downtown Santa Monica City Swipe App (Source: dtsmcityswipe.com)

Lichfields is continually exploring different means of engaging with previously harder to reach members of local communities and recognises the contribution apps can make. Closer to home, Greater Manchester is pioneering an interactive mobile-friendly map to highlight potential development sites city-wide. The

Greater Manchester Open Data Infrastructure Map combines various types of ‘big data’ - from water and transport networks to property prices and brownfield land - offering a comprehensive overview of the city’s infrastructure. Recently, an additional

map layer has been added, showing proposed development sites in the emerging Greater Manchester Spatial Framework. This layer combines sites allocated by the Council with those promoted by residents and developers. Users can also select specific sites to view the Council’s assessment(s) of each.

In Edinburgh, UrbanPlanAR, Linknode and Heriot-Watt University have produced a mobile augmented reality architectural visualisation platform for planners and local communities.

TrueViewVisuals is a commercial platform for architectural and infrastructural visualisation, which also attempts to better engage people in the planning process. The use of 3D data enables ‘in-field visualisation’ of proposed schemes. As such, users are able point their phone or tablet at a development site as if taking a picture and see a visualisation of the planned building on their screen – think Pokémon Go for planning! My colleague

Mark’s blog discusses this technique in further detail.

The use of apps in community engagement reflect the fast-paced world we inhabit, by allowing views to be given at a swipe or touch of a screen. Moreover, apps can simplify what might be otherwise regarded as long-drawn-out planning exercises into being something more tangible for local communities to grasp.

Technology, of course, is not the only way to improve and increase community engagement in planning, as not everyone is comfortable with using such platforms. However, it does present an additional tool for engaging with new groups – an opportunity which is constantly being tried, tested and refined.

[1] Town and Country Planning Act 1947.