Update 25 May 2019:

On 3 May, the government published its response to the October consultation

‘Supporting the high street and increasing the delivery of new homes’. Amongst the changes, the government confirmed they are introducing new PDRs which will allow A1/A2/A5 uses to change to office B1, and A5 uses to change to dwellinghouse C3 (subject to conditions and limitations, including floorspace limitations). These amendments are being brought forward through under

The Town and Country Planning (Permitted Development Advertisement and Compensation Amendments) (England) Regulations 2019, which came into force today.

The Government has not combined the A1-A3 use classes and has not yet amended the A1 use class, but said in its response:

"We intend to amend the shops use class to ensure it captures current and future retail models, which will include clarification on the ability of the A use classes to diversify and incorporate ancillary uses without undermining the amenity of the area".

23 November 2018:

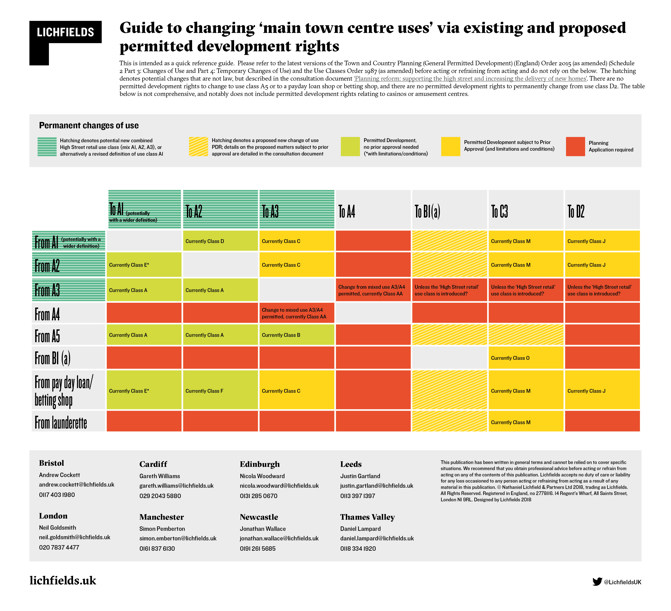

Lichfields'

Guide to changing ‘main town centre uses’ via existing and proposed permitted development rights shows the relevant temporary and permanent changes of uses that benefit from permitted development rights, and those currently being consulted on.

Alongside the Budget on 29 October 2018, the Government launched a consultation on “Planning Reform: Supporting the high street and increasing the delivery of new homes”, which includes (in Part 1) proposals to amend permitted development rights (PDRs) and retail-related use classes. The proposed changes could have a significant impact on the vitality of the country’s town centres.

That is the government’s intention. The Budget, the consultation’s webpage and consultation document clearly refer to “supporting the high street”, “taking a positive approach to their growth, management and adaption”, and at the same time “creating new homes” and “delivering new homes in the right places, without delay”.

The government is clear that the planning system has a critical role to play - rightly in our view - in “the future of our high streets and in underpinning the delivery of much needed new homes”. So the aspiration behind the latest PDR proposals is to “revitalise the high street, support businesses and deliver new homes”.

That is all unquestionably laudable, but will the proposals have the positive effects in practice, or will there be unintended negative consequences? And has the government thoroughly thought these through? We suspect that the consultation is seen as key input to that thinking process, to ensure the likely benefits clearly outweigh any potential harm.

Specifically, the proposed change of use PDRs would predominantly affect existing retail and leisure uses, and include the introduction of new PDRs to permanently change to office from retail. There is one new change of use PDR proposed that relates to housing: takeaways to residential.

Proposals to amend use classes and change of use PDRs

As the Lichfields guide shows, the changes of use proposed to be granted by PDRs from retail and other NPPF defined ‘main town centre uses’ (which do not require prior approval to change use permanently), would remain focussed on the “traditional” high street A class uses (with the exception of A4 pubs and bars), in what remains of the original change of use ‘ratchet’ from A5 to A1

[i] .

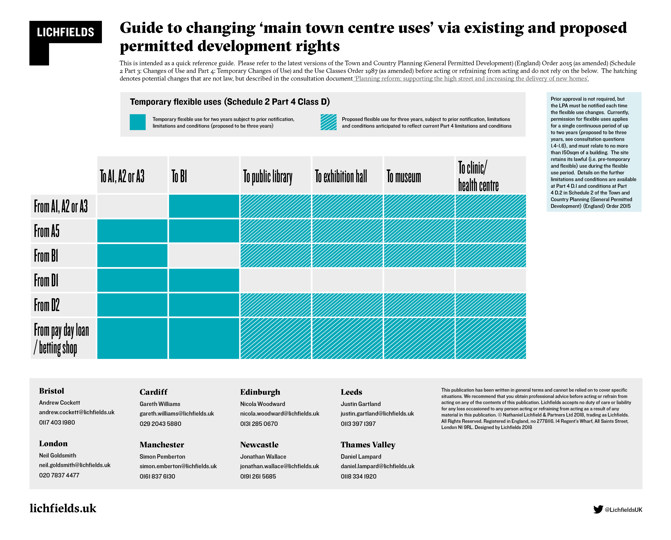

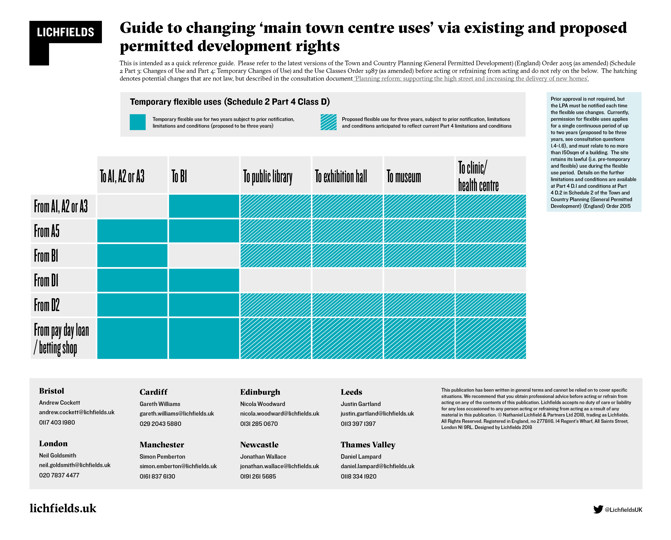

The government would like to introduce “a more flexible and responsive ‘change of use’ regime with new PDRs that make it easier to establish new mixed‑use business models on the high street”

[ii]. This objective reflects those of flexible temporary uses (see Image 2 below) when they were introduced five years ago

[iii].

Two alternatives are proposed to provide flexibility for retail:

- broaden the definition of use class A1 (shops), including removing the list of named uses “to ensure that it accommodates new and future business models and modern shopping preferences”; or

- create a new ‘High street retail’ class that would merge use classes A1-A3 (shops, financial and professional services, and food and drink) and potentially other uses

Providing a planning system within which town centres and other retail centres and locations can quickly adapt and accommodate market changes is certainly a way of supporting them. Although, beyond the protection of pubs, the system continues to seek to control lifestyles and there is no flexibility here: change of use to takeaways, pay day loan shops and or betting shops is not possible via either temporary or permanent permitted development rights.

Shopping centre owners are likely to welcome flexibility in the permitted retail planning use, as they can and do control and curate the tenant mix desired. For high streets though, it will be necessary for shop owners and local planning authorities (LPAs) to consider which centres and primary shopping areas are likely to benefit or not from the PDRs now proposed.

As the Lichfields guide shows, permanent change of use to residential, subject to prior approval, would be permitted from hot food take-aways (use class A5) , in addition to the existing PDRs to change from A1-A3 retail uses, pay day loan shops, launderettes, pay day loan shops and office, presumably still subject to a 150sqm floorspace limit. It is also proposed that all of these uses would be able to change permanently to office, subject to prior approval.

The combined effect might be termed a ‘quiet revolution’ as the proposals effectively create a new ratchet system for retail and town centres, with the permitted changes reflecting the amount of noise and disturbance that the proposed uses might typically generate compared to the current lawful use. Except now the lowest impact use is residential, followed by B1, rather than A1, which may lead to noise complaints from future residents (unless noise impact on future residents is added to the list of matters to be considered at prior approval stage).

The impact of these PDRs is also likely to be quiet in terms of the number of homes delivered too: MHCLG statistics

[iv] show that the ‘any other’ category of permitted development right, which includes retail to residential, has delivered just over 2,100 homes in the last three years, or less than half of a percent of all net completions. By comparison, office to residential conversions, which can operate at a greater scale and with no floorspace limitations, delivered nearly 8 per cent of net completions over the same period.

If retail to office and take-aways to residential PDRs are to have similar conditions to those attached to existing retail to residential PDRs, then their take up is likely to prove to be limited. Where they are taken up, their impact could be significant and varied, depending on, for example, whether there is loss of existing retail frontage or the removal of a long term vacancy.

But noise might be a particular issue if use classes A1-A3 are merged, and change of use from retail to restaurant is no longer development. Those ‘living above the shop’ may notice negative amenity impacts – noise, smell, disturbance - that are significant, but not so significant as to breach environmental impact regulations. It would also mean that huge A1 stores could become huge restaurants. From this perspective, a merger of use classes A1 and A2 would probably lead to fewer unintended consequences, albeit that this would not be a big leap from the existing PDRs.

The water has been tested before. It is more than five years since the flexible change of use PDRs were introduced, allowing temporary use of up to 150sqm of assembly and leisure, non-residential institution, pay day loan shops, betting shops and Class A retail (now excluding pubs) premises for office space. While the lawful use of the premises in flexible use does not change, if those flexible uses have existed without detrimental amenity or retail impact for two years, akin to any other temporary planning permission, this would help to assess and support a planning application to change the lawful use.

The prior notification system for flexible temporary uses was intended to be a monitoring device, but any outcomes of that monitoring have either not been reported or not reported widely. The proposed extension of the flexible PDRs to museums, exhibition halls, libraries and exhibition centres suggests that there have not been widespread significant detrimental impacts. The addition of these uses to the range of temporary flexible retail uses, particularly given the floorspace limitations, is likely to be very positive in terms of ‘vibrancy’, provided that there is an actual demand for such uses.

The government considers that “permitted development rights for change from retail and other high street uses would provide a quicker more certain route to enable business to adapt and help town centres to remain vibrant”. Flexibility between retail and leisure uses is logical in this respect, but are the permanent PDRs to office and residential really improving vibrancy? And would the proposed PDRs do this to a greater extent? These PDRs are likely to help secure active uses, but not necessarily vibrant ones.

And does the introduction of retail to office PDRs allow local planning authorities to plan for the positive approach to growth, management and adaptation of town centres sought by the National Planning Policy Framework - particularly the requirement to “define the extent of town centres and primary shopping areas, and make clear the range of uses permitted in such locations, as part of a positive strategy for the future of each centre”?

Certainly, the fragility of many of our town centres at present means that we must think deeply about the positive and any unintended negative effects that might manifest and frame the PDR accordingly.

Local planning authorities are likely to be giving significant thought as to whether some centres, for example the most successful centres in less need of “support”, will benefit from a further extension of permitted development rights away from retail, and accordingly whether Article 4 Directions should be imposed in certain circumstances.

Perhaps local planning authorities should look again at whether local development orders (which grant planning permission to specific types of development within a defined area)

[v] made in conjunction with Article 4 Directions that remove some of the new flexibilities could provide a bespoke solution for some town centres?

The consultation runs until 14 January 2019.

For more information on change of use permitted development rights more generally please see the

Lichfields Guide to Use Classes Order in England

[i] Via permitted development rights, changing to a use with a typically greater amenity impact to a use with a lesser amenity impact, but not back again, e.g. from A5 to A3, A2 or A1, or A3 to A2 or A1, but not A1 to A3 (now possible with prior approval) or A5[ii] Planning Reform: Supporting the high street and increasing the delivery of new homes[iii] According to the consultation “New opportunities for sustainable development and growth through the reuse of existing buildings” (DCLG, 2012), temporary flexible uses were intended to address concern that “some new business ideas are inhibited as seeking planning permission for change of use sometimes means a commercial opportunity is missed. Also some new businesses will only really be certain of their use class after being able to test the market and refine their business model”.[iv] Live tables on housing supply: net additional dwellings (November 2018 update)[v] Planning Practice Guidance regarding Local Development Orders