Following the ongoing response to the effects of climate change and impact of COVID-19 pandemic, future large scale solar and onshore wind energy generation with battery storage has a key role to play, as the UK plans its way through the significant economic and environmental challenges it now faces.

The Committee on Climate Change, in its May 2020 letter to the

Prime Minister and First Ministers in

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland sets out key principles to rebuild the nation whilst delivering a stronger, cleaner and more resilient economy. Lord Deben the CCC Chairman said ‘

The COVID-19 crisis has shown the importance of planning well for the risks the country faces. Recovery means investing in new jobs, cleaner air and improved health. The actions needed to tackle climate change are central to rebuilding our economy. The Government must prioritise actions that reduce climate risks and avoid measures that lock-in higher emissions.’

The global pandemic landed on UK shores, in quick succession to two storms in February 2020: Chiara and Dennis which caused some of the worst floods seen in the UK for 200 years with widespread damage which according to insurers will exceed £363m, a fraction of the £300 billion that the Treasury predicts will cost the exchequer this year with Britain facing the worst recession it has seen for over 300 years.

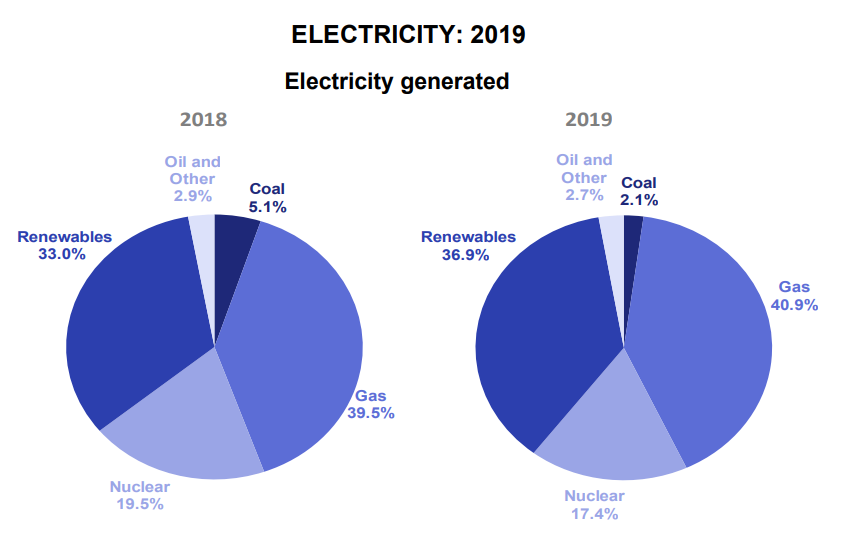

Renewables have overtaken fossil fuels as the main source of electricity in the UK for the first time after a notably windy season, and a slowdown in demand due to COVID-19. Solar, wind, biomass and hydropower accounted for 44.6 per cent of electricity supply between January and March 2020 (up 10% compared to 2019), as a result of increased capacity, (according to data from energy market analysts EnAppSys), exceeding UK fossil fuels by 36 per cent. Coal powered generation in the UK has fallen by an unprecedented 35% in the last month compared with the same period in 2019.

Source: UK Energy Press release. BEIS Press Release 26th March 2020

The UK is already committed to establishing a stronger low carbon based economy. In June 2019 the UK government passed legislation committing the UK to net zero greenhouse emissions by 2050, the first of the G7 industrialised nations to do so. To achieve this objective, the government will need increase the contribution of low carbon renewable energy sources to the UK’s electricity supply mix, in the main through an increase in solar; wind (both onshore and offshore), biomass and hydro power-based generation. Electricity generated from renewable sources has shown to be the only source resilient to the instability of these challenging times.

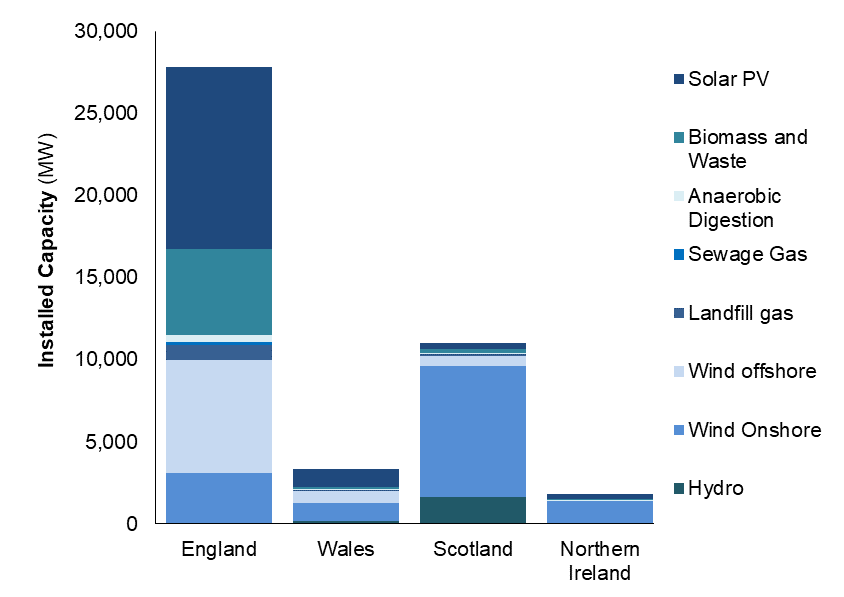

According to Government statistics, renewable energy capacity by the end of 2019 had increased across the UK to some 47.4 GW representing a growth of some 7% overall from the previous year. In England this was predominantly associated with the growth in offshore wind, with onshore wind and solar remaining static by comparison. In Scotland the majority of the increase was split between new onshore and new offshore capacity. Some two thirds of the increased capacity in Wales arose for onshore wind development. Almost all of Northern Ireland’s increase in renewable energy capacity arose for onshore wind installations. At the end of 2018, England accounted form 64% of the UK renewable energy capacity; Scotland’s share was 25%, Wales was 7.5% and Northern Ireland’s stood at 4.0%.

Renewable capacity and end of 2018 by technology and country

Source: National Statistics

In Scotland there is a commitment to meeting 100% of Scotland’s electricity demand from renewable sources by 2020, with a commitment to onshore wind as the lowest cost new build electricity generation in the UK.

To enable the move towards a stronger low carbon based economy, the UK government has provided assistance through subsidies to help the development and installation of new renewable infrastructure. In its latest form, the Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme was first introduced in 2014, with renewable projects competing for contracts in the first allocation round, which ran from October 2014 to March 2015. In February 2016, however, responding to pressures from landowning sectors, the then government made the decision that ‘Pot 1’ technologies such as solar and onshore wind would

no longer be able to eligible for compete in the CfD, leaving many large-scale solar and onshore wind assets on the drawing board following the removal of the Renewable Obligation scheme, which the CfD was intended to replace.

With the subsidy taken away, national planning policy in England reinforced the lockdown, by requiring that prospective wind proposal sites had to be identified in an area identified suitable for wind energy development within a local or neighbourhood plan; and, that following consultation, it would have to be demonstrated that the planning impacts identified by affected local communities had been fully addressed, and therefore the proposal had their backing. The effect of this policy in England, which still remains in place, was to give local people the final say in granting planning permission for wind energy development involving one or more wind turbines. The effect of this saw a marked reduction in onshore wind and large scale solar in England, but a continuation of such development in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Government had seen electricity generation from unconventional gas sources as a bridge to a carbon zero future, however, it ended support for this energy source in November 2019 following the publication of an Oil and Gas Authority report which concluded that it wasn’t possible with the current technology to accurately predict the probability of tremors associated with fracking. Separate proposals to change the planning process for fracking sites will not now be taken forwards.

With these factors in mind, a reported shift in voter attitude towards onshore wind power, the UK Government’s opposition to subsidising new onshore windfarms is now to be abandoned some four years after ministers scrapped support of new projects. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) announced in March 2020 that ahead of the Energy White Paper it would remove the block against onshore wind projects and large scale solar by allowing schemes to compete for subsidies alongside floating offshore wind projects, in a new auction scheme. The implications for the UK solar and onshore wind industry are immense.

Hugh McNeal, chief executive of RenewableUK, said: “The government is pressing ahead with action to meet our net zero emissions target quickly and at lowest cost to consumers and businesses”. “Backing cheap renewables is a clear example of the practical action to tackle climate change that the public is demanding, and this will speed up the transition to a net zero economy.”

With planning consent and technological lifetimes meaning that most existing onshore wind farms expected to last 25 years before needing to be decommissioned, or ‘re-powered’ with upgraded equipment, national and local planning policy in England will need to respond positively to facilitate the re-powering of existing onshore sites and granting planning permission for new facilities.

The Government’s Science and Technology Committee in its latest report August 2019, Clean Growth: Technologies for Meeting the UK’s Emission Reduction emphasised that ‘Although onshore wind power and large-scale solar power are low-cost and low-carbon, the deployment of new installations of these technologies has fallen drastically since 2015. The Government must ensure that there is strong policy support for new onshore wind power and large-scale solar power projects for which there is local support and projected cost-savings for consumers over the long-term. The Government should actively encourage and support local authorities to adopt planning practices that promote local support for such renewable energy projects.’

Notwithstanding the change in tack on subsidies for onshore wind, national planning policy (NPPF 2019, paragraph 154) presents a barrier to new onshore wind proposals in England. This policy barrier needs to be removed and replaced policy which aligns with the approach adopted throughout the rest of the UK. Extant planning practice guidance it is assumed will however continue to ensure that the need for renewable energy doesn’t veto the material planning concerns of local communities and the need to safeguard the environment.

With the Government’s commitment to move quickly to meet its net zero commitment by 2050 in place, it must ensure this potential is maximised throughout all of the UK. With the overwhelming majority of local authorities proclaiming a firm commitment to the campaign against climate change, a change in national policy approach will ensure local authority local development plans are in in alignment with the national consensus. Within the UK as a whole there has been progressive growth in renewable energy generation with the corresponding fall in energy generated from fossil fuel. For this momentum to be maintained in the months and years ahead, the government’s strategy for economic stability and recovery in meeting the challenges presented by Corvid 19 recovery need to ensure this does not lock in higher emissions.