The Prime Minister’s Conservative Party conference speech confirmed speculation that a change in direction is afoot on planning reform

[1]. Diminished is the thinking that led to the White Paper and the ‘mutant algorithm’. Ascendant is ‘levelling up’ and directing development to brownfield sites

[2]. The Daily Telegraph headlined its report of the speech with “

PM pledges no homes on green fields”

[3]However literally we should interpret the PM’s rhetoric

[4], the tilt towards brownfield and away from greenfield is worthy of exploration. It may be a response to the politics of the past twelve months, but it is not a new policy outlook, having echoes of the brownfield-first policy of the Labour Government in the late 1990s, that culminated in Planning Policy Guidance Note 3 (PPG3) in 2000.

The current BBC documentary series on New Labour tells the political story of that era

[5]. Unsurprisingly, its planning agenda is not centre stage, but might a review of PPG3 help frame consideration of the latest brownfield zeitgeist? This blog looks back at the genesis of PPG3, unpacks its core elements, and sketches out what happened to housing delivery.

Emergence of the policy

New Labour came to power in 1997 with a focus on urban renaissance, but it went with the grain of the agenda from the previous Government

[6] which had already suggested an “

aspirational target” of 60% of new homes on brownfield land

[7]. In 1998, Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) John Prescott published

Planning for the Communities of the Future[8]a policy statement which introduced the idea of ‘brownfield first’, described as:

“a sequential and phased approach to the development of all sites, which means there will be a general preference for building on previously-developed sites first, especially in urban areas”

This was not a ‘brownfield only’ policy:

“The principle of reusing previously-developed sites is, at first sight, the most sustainable option. However, reuse of land (and buildings) is only one aspect of sustainable development. Other aspects relate to the resource and energy implications, including reducing the need to travel. Not all previously-developed land is equally attractive to develop in sustainability terms. … Thus, in sustainability terms, some forms of greenfield development may be more attractive, such as extensions to urban areas in public transport corridors…

This suggests that criteria may be needed for deciding a sequence for development at regional, and particularly local, levels. This means using a more sophisticated approach to the choices of both the form and phasing of development, with the clear aim of creating more sustainable patterns of development.”

On how this related to meeting housing needs, Government was cognisant of affordability, but sought to downplay the idea of the 4.4m households by 2016 as a binding target, by introducing “plan, monitor and manage”. In his statement to Parliament, the DPM said:

"The dilemma is clear cut and affects us all - how to accommodate more households and, at the same time, protect our precious countryside, without rents, house prices or homelessness spiralling upwards. It is not just a matter of how many households but where they will live….

In order to achieve greater flexibility, we are determined to get away from a simplistic 'predict and provide' approach in housing, as we have done for road building. We will treat the household projections as guidance, not house building requirements. Moreover, we will allow for greater flexibility in adjusting regional and local plans to ensure local provision is meeting local need over time…” [9]

In 1999, the Government consulted on a draft of PPG3, which introduced the sequential approach. That summer, the Urban Task Force reported

[10].

PPG3: brownfield-first planning policy

PPG3 was published in March 2000

[11]. It comprised a number of core elements:

Housing targets were to be set at a regional level based on a “realistic and responsible approach to future housing provision, assessing both the need for housing and the capacity of the area to accommodate it” (No tilted balance then!). Growth was to be directed to “areas where previously-developed land is available … in preference to developing greenfield sites.”

Land supply was underpinned by a brownfield target of 60% “in order both to promote regeneration and minimise the amount of greenfield land being taken for development” with urban capacity studies used to identify the potential of brownfield land. In identifying sites for allocations “authorities should follow a search sequence, starting with the re-use of previously-developed land and buildings within urban areas identified by the urban housing capacity study, then urban extensions, and finally new development around nodes in good public transport corridors.”

Site selection was based on criteria in Paragraph 31 of the PPG3, but deliverability was not one of them. Brownfield sites were to be preferred to greenfield release unless they performed “so poorly” as to preclude their use for housing.

The phased release of sites was to be determined in local plans based on the sequential approach, with plans required only to identify land for the first five years (and no requirement for it to be deliverable, as now), with plans to be “

updated is reviewed and rolled forward at least every five years”. The only concession to deliverability was the where it said: “

it is essential that the operation of the development process is not prejudiced by unreal expectations of the developability of particular sites nor by planning authorities seeking to prioritise development sites in an arbitrary manner.” Guidance was produced to assist in this process.

[12]

Enforcement of the policy included the Town & Country Planning (Residential Development on Greenfield) Direction 2000, requiring local authorities to refer planning applications on greenfield sites of at least 5ha or 150 dwellings - including on existing local plan allocations - to the Secretary of State for him to decide whether he wanted to make the determine the application following a public inquiry. In the first ten months of PPG3, the Secretary of State had ‘called-in’ 20 greenfield housing applications under the Direction or as a departure, with a further nine pending a decision

[13].

What was the impact?

In 2003, Lichfields was commissioned by ODPM to carry out research on the implementation of PPG3

[14]. We found an inconsistent picture across the country as to how well the policy was being applied. Half of local authorities had reviewed their greenfield allocations, and most had either completed or were underway with urban capacity studies, but there was far slower progress on local plan preparation, with only 13% of local plans and 35% of structure plans adopted. A third of local authorities – particularly in the South East – had not begun preparing local policies (in effect they banked the restrictions on greenfield release as early as 1998 without putting in place a strategy to respond to housing needs).

The Study found that barriers to implementation of PPG3 included the slow pace of local plan production and lack of resources. Plus ça change.

A historic perspective on the brownfield-first policy is provided by Andrew Prichard, former manager of the Regional Planning Body in the East Midlands

[15]. He found:

- Regional Planning Guidance targets for housing provision aggregate to around 150,000 homes[16] but with a different regional distribution: numbers were higher in the North East, Yorkshire and Humber and the West Midlands. In the North West, the Government cut housing targets by 15% to reduce greenfield development. In the South East, the Government split the difference between the SERPLAN intentions and the conclusions of Professor Stephen Crow (Inspector) who had “demolished” them.

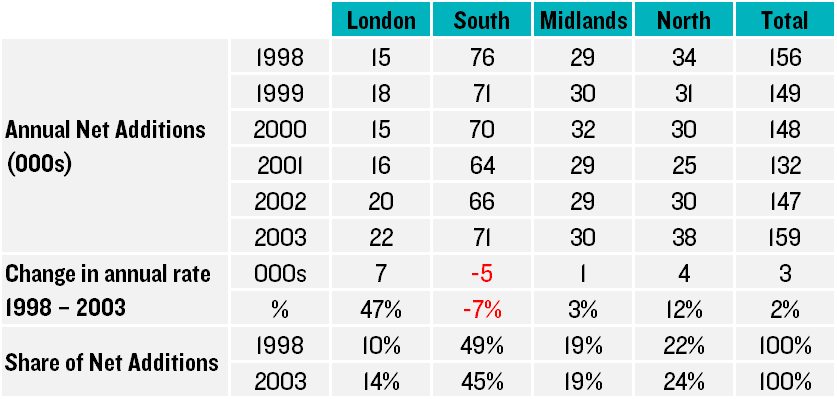

- The proportion of brownfield increased (CPRE reported it to be 67% by 2005). However, net housing additions fell from 156k per annum in 1998 to a low of just 132k in 2001 despite “increasing economic buoyancy”. House building was clearly not keeping up with household growth, with shortfalls of 90,000 homes alone in 2001 and 2002.

The figures for net housing additions 1998 – 2003 are shown in the Table below.

Source: DLUHC: Table 109 Dwelling stock: by tenure and region, from 1991 (figures may not sum due to rounding)

Whilst the rate of completions nationally had recovered by 2003, there was still a 7% reduction in the south, and national supply was historically low. London was the principal driver of increase.

Andrew Prichard comments:

“The extent to which PPG3 was responsible for the mismatch is of course difficult to fully establish. However, it represented a very significant shift in locational policy for developers and land owners and was strongly enforced by central Government. Research by Savills in 2004 indicated that the immediate effect of PPG3 was to ‘restrict greenfield availability rather than increase the availability or capability of development of brownfield sites’ – which in turn had implications for land prices and housing supply.”

The Barker Review of Housing Supply Interim Report (2003) observed that:

“The sequential test introduced in PPG 3 requires local authorities to release land for housing development in an order of preference that prioritises brownfield sites. It is not the intention of the policy to restrict land supply but some local authorities appear to have overinterpreted it to the detriment of housing being delivered. Indeed research from ODPM supports this point, arguing that local planning authorities understand ‘brownfield first’ but also erroneously believe PPG3 says ‘greenfield never’.

The ‘prematurity of sites’ is often a reason for the refusal or delay of applications for housing developments. However, priority sites may not always be immediately available or suitable for development. In some local authorities, this policy is used to block development rather than actively manage the release of land.”[17]

A change in direction

By 2003, there was a shift. The DPM launched

Sustainable Communities: Building for the Future, with plans to

“tackle the housing shortage, especially in London and the wider South East by creating conditions in which private house builders will build more homes of the right type in the right places” [18]. This approach included the four new growth areas

[19].

Barker’s final report (2004) said the planning system should be more responsive to market signals

[20]. On the brownfield first policy, it recommended that:

“PPG3 should be revised to require local planning authorities to be realistic in considering whether sites are available, suitable and viable. Any site which is not available, suitable and viable should be disregarded for the purposes of the sequential test.”

In 2006, PPG3 was replaced by PPS3

[21]. This maintained the 60% brownfield target, but crucially brought back the requirement for a rolling five-year land supply of

deliverable sites and set a requirement for

developable land for years 6-10 and, where possible, 11-15. By 2008, housing supply was 40% above its 2003 level. This policy was carried forward into the NPPF (2012) alongside the presumption in favour of sustainable development. This dual approach – of allowing local authorities to select brownfield sites in preference to greenfield, but still ensure they have a portfolio of sites that will secure a sufficient supply of housing in reality – remains part of the current policy framework

[22].

Ten lessons for today

This canter through one aspect of New Labour history tells us something about the factors this Government should consider if it is genuinely contemplating a more overt brownfield-focused policy:

- Even at its zenith, PPG3 was never a brownfield only policy, even though some Councils sought to interpret it as such. Plan makers were able to choose to release greenfield land for housing.

- Such a policy (that takes effect as soon as there is an expectation of a change[23]) will result in an immediate reduction in new housing supply, with the greatest downward impact in the south of England, where affordability problems are greatest.

- A brownfield-based policy does not, in of itself, make brownfield land more deliverable for housing. Barker’s interim report found that 69% of all National Land Use Database brownfield sites were not suitable for housing development and over half of the suitable land was in an existing use.[24]

- There is no evidence there is enough brownfield land, in any region, to deliver anything close to 300,000 extra homes per annum[25]. CPRE’s annual review of brownfield land[26] identifies capacity for 1.3m homes (1.1m of which was on brownfield registers, and 0.6m already consented). Registers can be a helpful indicator of brownfield potential, but crucially a) local authorities’ assessments of site deliverability are not independently tested; and b) they measure capacity looking ahead 15 years. At best it would equate to less than 87,000 homes per annum. In the north of England, the brownfield register capacity equates to just 44% of the Standard Method over that period[27]. In London, the South and Midlands, it is less than a quarter. Relying on brownfield land alone is likely to reduce the supply of affordable housing rather than increase it.

- The CPRE analysis also highlights that brownfield capacity is not a silver bullet for putting more growth in the north. Of the 1.1m homes capacity on brownfield registers, 55% are in London and the South of England, compared to 45% in the midlands and the north (almost exactly in proportion to population).

- PPG3 relied on regional planning to do the hard work of strategic spatial choices. Unless the Government chooses to introduce a new strategic planning tier, attempts to skew housing targets towards brownfield areas, and to the north of England, will require a further recalibration of the Standard Method.

- Directing housing targets to urban areas does not itself drive up the supply of brownfield land. The December 2020 changes to the Standard Method added 35% to the housing need figure for the 20 largest cities, but it is already clear there is no realistic prospect of this being met; plan makers in London, Leicester, Southampton, Bradford are among those already stating they do not have the land capacity to meet the inflated figure[28].

- The practical limitations to the flow of brownfield development help explain why, throughout the life of PPG3, net housing additions hovered around half the 300,000 figure. The subsequent coupling of a brownfield focus with a parallel requirement to have a realistic supply of land (in PPS3 and now in the NPPF) coincided with an increase in supply.

- It impacts on mix too. An overzealous drive for brownfield leads to high density flatted development in town and city centres. This may not be undesirable itself, but the rationing of land release means this can come at the expense of family homes with gardens, which may be what is most needed to make some cities attractive to families.

- The growth in brownfield development that occurred in the second half of the 2000s coincided with a boom in buy-to-let mortgages[29] and a major public sector funding of housing-led regeneration programmes. Looking at the situation today, one would need to understand whether equivalent market drivers exist to accompany any change in policy, and bridge the gap between rhetoric and real-world delivery.

[1] Conference speech text here[2] In this blog ‘brownfield’ is used as shorthand for previously developed land (or PDL).[3] Daily Telegraph article here (£)[4] Welywn Hatfield Council has interpreted it very literally and put its delayed (very delayed) local plan on hold – see here.[5] Blair & Brown: The New Labour Revolution available on BBC iPlayer[6] For example the 1995 White Paper: Our Future Homes – Opportunity, Choice, Responsibility included proposals for “the planning system and public investment to encourage more development in existing urban areas and less on greenfield sites” and the aim to “build half of all new homes on re-used sites”,[7] In its 1996 Green Paper – Household Growth: Where Shall We Live – which looked at how to address the 4.4m additional households expected between 1991 and 2016.[8] Available here[9] Available on Hansard Volume 307, debated Monday 23rd February 1998[10] The Urban Task Force was chaired by Lord Rogers. Its Mission Statement was “The Urban Task Force will identify causes of urban decline in England and recommend practical solutions to bring people back into our cities, towns and urban neighbourhoods. It will establish a new vision for urban regeneration founded on the principles of design excellence, social well-being and environmental responsibility within a viable economic and legislative framework.”[11] The 2000 PPG3 is available here[12] Planning To Deliver - The Managed Release Of Housing Sites: Towards Better Practice available here[13] Written Answer in Hansard[14] PPG3 Implementation Study (2003) available here. This blog author was part of the research team.[15] In Chapter 3 of the English Regional Planning 2000-10, edited by Corinne Swain, Tim Marshall, and Tony Baden[16] Broadly equivalent to the 3.8m extra households set out in the 1996-based household projections.[17] The Interim Report of the Barker Review is available here[18] Available here[19] Thames Gateway; Milton Keynes/South Midlands; Ashford; London - Stansted – Cambridge. These flowed from recommendations of Professor Crow’s report on the South East Plan.[20] The Final Report of the Barker Review is available here[21] PPS3 (2006) is available here[22] For example, see paragraph 120 of the current NPPF which sits alongside paragraph 68[23] As evidenced by Welywyn Hatfield’s pre-emptive pause of its Local Plan following the PM’s Conference speech[24] See para 9.9 of the Interim Report: 32% was subject to flood risk or in the Green Belt; and 58% was in weak housing markets (which would impact on values capable of overcoming inevitable abnormal costs). Just 31% was in neither category, but most of it was already in use, leaving just 11% available for development. Add on to this, some of the 11% would have site-specific constraints. [25] This was clear from the NLUD data, as this 2014 Lichfields publication showed[26] CPRE – Recycling our Land: The State of Brownfield Report 2000. Available here[27] Based on the Standard Method as calculated at December 2020 to correlate with the CPRE Brownfield Register base date.[28] Examples are in this Inside Housing article[29] Reported as representing 30% of all house purchase mortgages by 2008 (Sprigings N, 2008, “Buy-to-let and the wider housing market” People, Place & Policy Online 2(2) 76–87).