Update 5 February 2024: The Government has published updated planning practice guidance on housing supply and delivery, including the following:

“Both the 5 year housing land supply and the 4 year housing land supply that authorities should demonstrate for decision making should consist of deliverable housing sites demonstrated against the authority’s five year housing land supply requirement, including the appropriate buffer."

__________________________________________________

The Government has finally published much anticipated changes to the National Planning Policy Framework (‘NPPF’) and related changes to the operation of ‘Five Year Land Supply’ (‘5YHLS’) and the ‘Housing Delivery Test’ (‘HDT’). See here to take a look at the changes yourself:

My blog last year (

Buffer the Land Supply Slayer) reviewed the then draft changes to 5YHLS and its ending struck a bit of a depressing tone: concluding that more Local Planning Authorities (‘LPAs’) would be able to demonstrate a 5YHLS but fewer homes would ultimately be built.

Reviewing the changes now adopted, the Government has not implemented its previous proposals in full. They have listened to concerns regarding the impacts of the proposals on housing supply however and, in doing so, have tried to strike a new balance between the push for plan-making while retaining some release valve for where plan-making fails. In summary, the changes are:

-

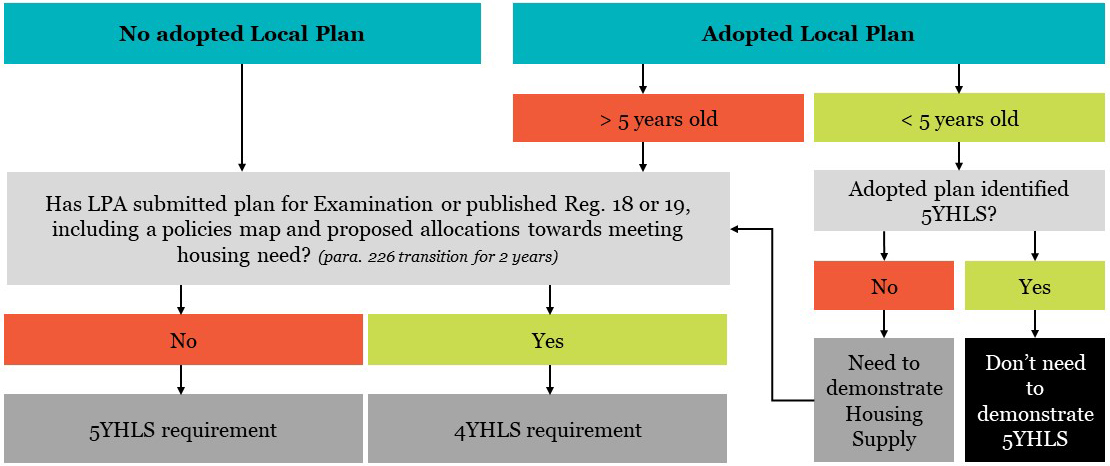

LPAs with a plan adopted in past 5 years (in most cases) don’t need to demonstrate a 5YHLS (some caveats apply to the determination of existing applications);

-

LPAs at the Reg.18 or Reg.19 stage (with caveats out the contents of relevant material) or with plans submitted for examination only need to demonstrate a 4-year supply;

-

5% and 10% buffers are gone but 20% buffers remain;

-

Oversupply will count towards 5YHLS in the future but how this works in to be determined;

-

The eligibility criteria for Annual Position Statements is now wider; and

-

Paragraph 14 has been beefed up to protect areas with made neighbourhood plans.

The below flowchart sets out how 5YHLS now operates and more detailed analysis of the changes and potential implications are set out below.

Have a plan adopted in past 5 years? Then be free of 5YHLS

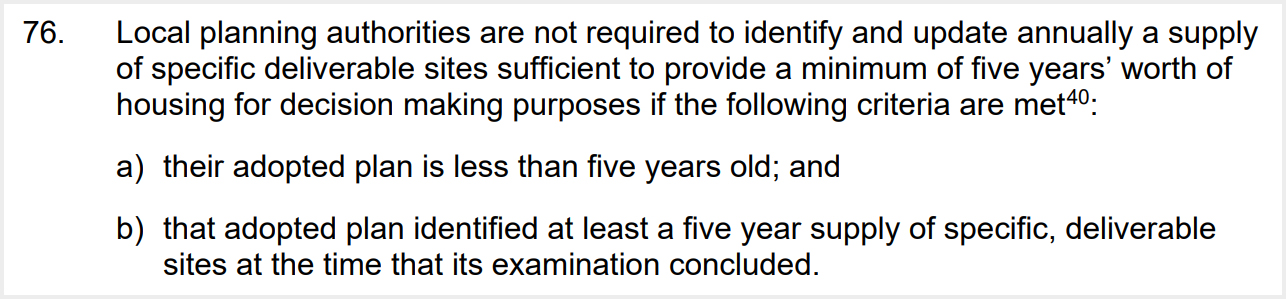

LPAs that have an ‘up-to-date’ plan are no longer required to identify and update annually a 5YHLS. Paragraph 76 of the Revised NPPF (Dec 2023) defines whether a plan is up-to-date as per the below extract:

This new policy means – as set out in the Government’s consultation response – the protection of Paragraph 76 only applies only to plans that have been examined by an Inspector in the past five-years. It does not apply to an LPA’s own Reg.10a review of its plan at the 5-year date. The provision is clearly aimed at pushing LPAs to maintain up-to-date and better plans (by virtue of them needing to be examined) to achieve sustainable development goals and provide sufficient housing (as per amended Para 1 of the new NPPF).

Our reading of part (b) of paragraph 76 is that spatial development strategies – i.e., London Plan – or other forms of plans that don’t identify allocations to meet a need won’t offer 5YHLS protections. Those without an up-to-date plan will continue to have to demonstrate a 5YHLS.

But….. (very important caveat)

The protections of paragraph 76 do not apply for the determination of applications that were submitted prior to 19 December 2023 (i.e. the Revised NPPFs publication date) in accordance with Paragraph 224, and footnotes 79 and 8.

If, on 18 December 2023, a LPA had an up-to-date local plan but was unable to demonstrate a 5YHLS, it cannot benefit from the paragraph 76 protection for pending applications and will need to apply the titled balance (but at the same time can account for wider changes to 5YHLS – as discussed below).

Two years of transition: 4-Year Supply for some

In much the same as the previous draft text, paragraph 226 of the Revised NPPF sets out that LPAs that meet certain criteria will only need to demonstrate a four-year (not five-year) supply; those criteria being:

-

LPAs with a plan submitted for examination; or,

-

LPAs with a Reg.18 or19 plan that includes both a policy map and proposed allocations to meet a requirement.

The above applies immediately and will do so until December 2025. What a ‘policy map’ is will likely be a point of debate in the short term (i.e. do a series of maps in a plan constitute a ‘policy map’?).

The question follows, how does one calculate a four-year supply?

Our reading of the text at paragraph 77 and 226 is that it is a four-year period test. So, you would only consider the supply expected to be built out over the next four years and compare that to the appropriate requirement for that same four-year period (potentially with a 20% buffer).

This is very different to testing whether over a five-year period an LPAs supply is more than four years’ worth which we do not consider to be an approach supported by policy. For example, the former paragraph 14 (c) of the NPPF (September 23) stated:

“14. In situations where the presumption (at paragraph 11d) applies to applications involving the provision of housing, the adverse impact of allowing development that conflicts with the neighbourhood plan is likely to significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits, provided all of the following apply:

[…]

- c) the local planning authority has at least a three year supply of deliverable housing sites (against its five year housing supply requirement, including the appropriate buffer as set out in paragraph 74);”

(our emphasis)

The revised NPPF however is not worded akin to the above. Paragraph 77 instead states that LPAs should identify “supply of specific deliverable sites sufficient to provide either a minimum of five years’ worth of housing, or a minimum of four years’ worth of housing if the provisions in paragraph 226 apply”.

The implication of the above it that over a five-year period an LPA might well have more than four years’ worth of supply (i.e. if the five-year requirement equates to 1,000 dwellings, they might have a deliverable supply of more than 800 units). However, many of those new homes might be on sites with outline permission or allocations that are expected to come on stream in ‘year 5’. Were the assessment to be focused solely on a four-year period, that ‘year 5’ supply would not be counted. Suddenly the could LPA get caught out and find itself unable to demonstrate the requisite requirement.

This is one to watch as we are not sure this is how the policy was intended to work.

Greater reliance on the HDT

The changes above mean that many LPAs will either only need to demonstrate a four-year supply (for the next two years) or will not need to demonstrate a 5YHLS at all (as their plan was adopted in the past five-years or will soon be). The question is then, how do we ensure the homes needed are actually built? The answer: the HDT.

The ultimate sanction of the HDT – the presumption of Para 11(d) being engaged where a measurement is below 75% – will apply to all LPAs regardless of when a plan is adopted or at what stage of plan-making an LPA is at. There is no ‘get out’ of this provision as was proposed in last year’s draft text (which related to how many homes had been granted permission in the same assessment period). Comparing the 2022 HDT with PINS data on ‘strategic plan progress’ there are c. 10 LPAs, at the time of writing, with an up-to-date plan but would fail on this measure.

Other 5YHLS changes:

Other than the above, the following is of note:

-

Buffers: 5% and 10% buffers are gone. But 20% buffers remain. The 20% buffer only applies where an LPA is not protected by paragraph 76 and scores below 85% in the latest HDT (paragraph 79);

-

Oversupply: One for the future, but the NPPF makes it clear that past ‘oversupply’ will be counted in an LPAs assessment of whether it can demonstrate a 5YHLS. However, how it is counted is unknown. Details of this will be published in future changes to Planning Practice Guidance (which do not accompany the NPPF at this time) (paragraph 77);

-

Monitoring supply: While some LPAs will not need to identify and annually update a 5YHLS, all LPAs should set out their deliverable land supply against an adopted housing requirement (paragraph 75); although critically, there is no incentive to do so or punishment for failing to do so. Notwithstanding, this means developers should still be able to calculate an LPAs 5YHLS supply – even if said LPA benefits from paragraph 76 – and demonstrate that there isn’t sufficient supply coming forward; adding weight to a housing case.

-

Annual position statements: Paragraph 78 now confirms that any LPA not covered by the provisions of Paragraph 76 can now submit an Annual Position Statement (‘APS’) to ‘confirm’ (i.e. fix) a 5YHLS. Under the previous NPPF, the eligibility criteria to prepare an APS greatly limited their use so this is a sensible change; and

-

Neighbourhood plan protections: The protections afforded by Paragraph 14 to areas with neighbourhood plans have been made stronger. It now applies to neighbourhood plans for five-years after being made (previously being two years).

Implications

Overall, it is clear that 5YHLS no longer has the teeth it once did (especially for the next few years), but neither is the wider system toothless when combined with the HDT. Considering the changes:

Incentivising plan making:

-

The protections afforded by paragraph 76 place a much greater emphasis on plans being consistently made and examined every five-years. This proposal – while risky (as we will come on to) – is far better than tying the benefits of paragraph 76 to having an up-to-date requirement (as was previously proposed). The former proposals were far too open to abuse while the new approach ties in a third-party examination of the supply.

-

The four-year transitional arrangement might also help some LPAs bridge the gap to allow adoption an up-to-date plan and in doing so protect them against speculative development (albeit that it might also hinder some as set out above). While a plan-making incentive this measure will have some negative impact on housing supply in the shorter term, but it may yield longer term supply benefits (assuming new plans actually plan for sufficient numbers of homes – a big ‘if’ in the context of other changes to the NPPF).

The risky bit: lagging indicators

-

Once plans are adopted and paragraph 76 applies, the HDT will be the only way to tell if they are actually delivering as intended. The HDT is a lagging indicator and shortfalls will take years to show up in it. At the same time, there is also no real incentive for LPAs protected by paragraph 76 to monitor supply annually to enable them to respond ahead of time to any shortfalls in deliverable supply.

-

This all inbuilds risk. The lag of the HDT combined with the long lead-in times to prepare applications in response to a failed HDT (<75%), get said application submitted and approved, and then build out that permission will mean shortfalls might not be addressed for a significant period of time.

-

Looking at this ‘glass half empty’, an LPA protected by paragraph 76 may coast for five-years and then be left with a considerable problem once it comes to review its plan if they are not monitoring effectively post adoption. This will be at a point where it’s too late to bring forward supply given known lead-in times.

Examining and preparing plans:

-

In this context, presumably local plan inspectors will need to examine a plans deliverable supply more intently knowing the supply might not be challengeable for some years to come and will really want to be sure it will actually be delivered.

-

Furthermore – and being quite ‘glass half full’ here – LPAs might be incentivised by the changes to paragraph 76 to take the tough choices on future supply (i.e. years 6-10 and beyond) now to help themselves in future plan reviews. If an LPA allocates sufficient supply in these periods or tees up work through policy to enable the identification of much longer-term supply (i.e. Garden Communities), then plan reviews should be a simple affair.

-

One would hope that if you really focus on years 6-10 and beyond, the five-year supply will eventually take care of itself at examination next time around.

Final thoughts

Overall, we are in a better position than we thought we were going to be this time last year. Things still are not really ‘great’ though.

It will remain to be seen though whether, given wider changes to policy now adopted and future changes to the planning system to come, LPAs plan for sufficient numbers of homes and in doing so allocate a sufficient mix of sites (in terms of size and timing of delivery) to ensure needs are met.

Lichfields will undertake more analysis on the revised NPPF in the coming weeks. Subscribe to our blog for updates.