The energy industry experienced a year like no other in 2023 as record amounts of energy from renewable sources were generated in the UK. Research suggests that approximately 43% of the UK’s electricity was made up of solar, wind and biomass, a 3% increase from 2022 and the largest share of the fuel mix since 2016

[1]. The third quarter of 2023 saw an increase in this figure, attributing 44.5% of our electricity to renewable sources, making strong progress towards the governments targets to deliver a decarbonised power sector by 2035 and net zero by 2050

[2].

Energy crisis

Nevertheless, energy bills remain high as the majority of our power comes from non-renewable sources. The UK, partly due to its dependence on gas for heating and electricity generation, has been particularly exposed to the energy crisis sweeping across the world, importing approximately 50% of its gas from the international market

[3].

The increased demand of energy during the post-Covid reopening of economies coinciding with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has squeezed gas supplies in Europe and consequently caused a steep rise in the wholesale price of gas. To put a value to this, prices in July-September 2023 were approximately 60% higher than in winter 2021/22

[4]. However, energy prices would have been even higher if the government had not invested in renewable technologies over the last decade

[5].

The UK, the first major economy in the world to legislate a binding target to reach net zero emissions by 2050 currently ranks 13

th out of 120 countries on the Energy Transition Index 2023

[6]. Considered a consistent performer, the UK demonstrates

“a strong enabling environment for energy transition, particularly on dimensions such as education and human capital, infrastructure, and regulation and political commitment”

[7]. However, recent reform has resulted in some radical adjustments to the net zero agenda somewhat politicising the climate crisis in doing so. Moreover, the current strategy is heavily reliant on private investment to hit net zero by 2050, making policy consistency even more important.

Closing the gap

The NPPF states that the planning system should support the transition to a low carbon future (paragraph 157). Current guidance stipulates that;

“Increasing the amount of energy from renewable and low carbon technologies will help to make sure the UK has a secure energy supply, reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow down climate change and stimulate investment in new jobs and businesses”.

However, local politics often interfere with this national strategy as local level planning policies often omit the importance of location in the siting of these technologies, and instead stress the need to adapt to climate change and deliver a low carbon future without establishing a more detailed strategy about how this need can be met.

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) latest report ‘Renewables 2023’ stipulates that under existing policies and market conditions, global renewable capacity is forecast to reach 7 300 GW by 2028, falling short of the goal set at the COP28 climate change conference.

Aggravated by the slowness of the Local Plan review process, recent policy reform, and the threat of a government re-shuffle, community opposition is perceived as one of the largest obstacles to getting new projects approved

[8]. However, by overcoming current challenges, implementing existing policies more quickly and removing cumbersome administrative barriers, the gap can be closed

[9].

Introducing battery storage

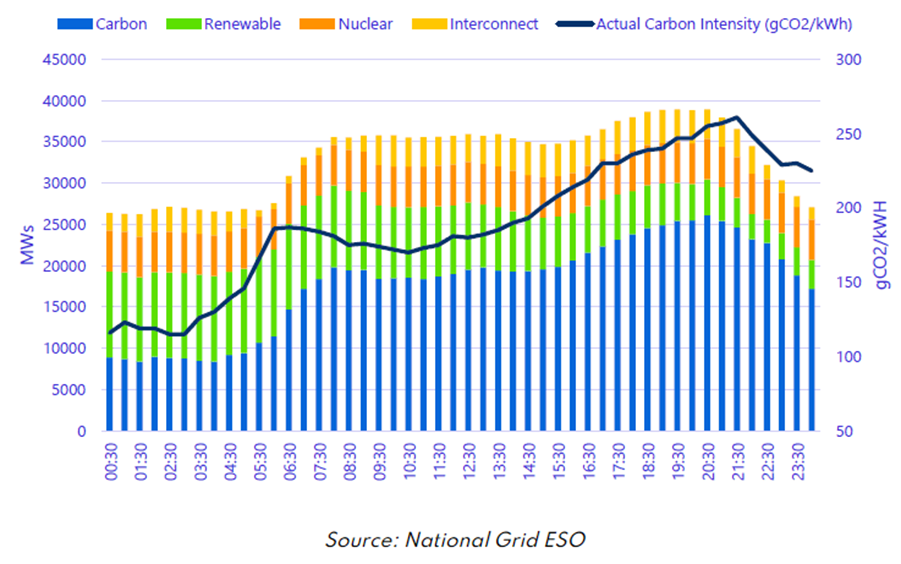

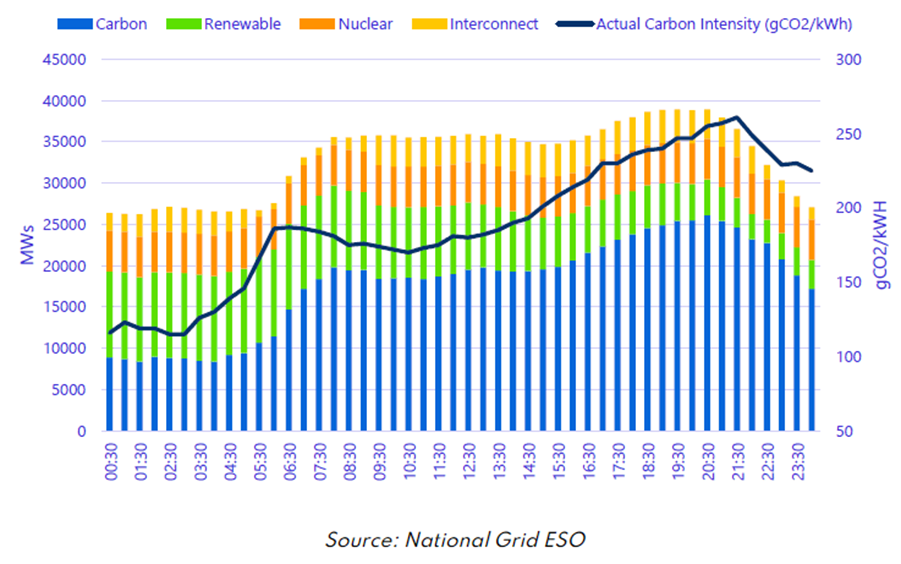

Because renewable sources like wind and solar power are intermittent by their nature, the ability to store intermittent power has become ever more important. The increasingly complex mix of generation methods employed, and the significant changes in overall demand at different times of day, means that the carbon intensity of grid power changes substantially at different times.

Typically, as shown in the figure above, electricity is less carbon-intensive overnight. By introducing Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) to the grid, low carbon energy can be stored and discharged during the day rather than using more carbon-intensive grid power. With transmission losses associated with the ‘transport’ of electricity, the closer the location to the substation, the more efficient and effective its contribution to satisfying local demand. However, as such facilities do not produce energy themselves, BESS applications fall into the ‘grey area’ of English planning policy, considered an enabler of a decentralised grid system rather than a facilitator.

For better or worse, the visual and other amenity perceptions of energy systems drive much of its policy debates. Unfortunately, the human impulse to often try to protect the status quo and resist change is impeding the UKs energy transformation and as such the industry needs to think ahead. The current planning system gives campaigners the leverage developers lack and despite these systems providing essential infrastructure, local opposition can be a key reason for planning applications failing.

Looking forward

To reach the UK’s 2050 net zero emissions targets a balance needs to be struck, including measures to reduce uncertainty to help the UK deliver a net zero energy system that is affordable and secure.

A market-wide strategy, including government targets, policy support and market reform is required to facilitate the significant growth in distributed flexibility

[10]. Furthermore, policy needs updating to reflect the ever-evolving advances in renewable technology and its locational requirements relative to grid connections. Also, more government engagement (at national and local levels) is needed to explain to communities the unprecedented climate change challenges that lie ahead, the scale of the effort needed to deliver essential renewable energy technologies, and the operational necessity for areas around existing and planned new substations (often in the countryside) to host renewables technologies and battery storage.

The scale of investment needed will depend on the degree to which the UK is able to make the most of flexible solutions and optimise the placement of generation and storage in relation to demand. A more strategic approach is needed to ensure Britain builds an energy system and electricity network that minimises consumer costs and disruption while maximising the efficiency of the grid.

Only through this kind of action can the UK deliver on its net-zero targets and reap the economic benefits of the clean-technology revolution.

[1] Electrical Review

[2] Gov.UK

[3] ONS

[4] The House of Commons Library

[5] Electrical Review

[6] The Energy Transition Index benchmarks countries on their current energy system performance and provides a forward-looking measure of transition readiness (World Economic Forum).

[7] World Economic Forum

[8] Connected Energy Solution

[9] International Energy Agency

[10] NGFES