We have had the manifestos and the General Election looms. In light of the opinion polls, the prospect of a change in government brings with it an opportunity to address a long overdue reboot of the planning system’s function as an enabler of national and local economic growth.

Whilst economic growth and wealth creation feature centrally in manifestos, behind the political messaging stands a stark fiscal reality. The pandemic and cost-of-living crisis has led recent governments to spend and borrow on an unprecedented scale, and with the tax burden now higher (and rising) than at any time since 1950. But with the main political parties committed to reducing the ratio of public debt to GDP by the end of the next parliament, and promising no further increases in headline taxation levels, there is essentially only one option if debt levels are to be reduced and public services paid for – to turbo-charge the UK economy, and to do it quickly.

Much analysis and debate has been devoted to the subject of planning reform, particularly in the development of solutions aimed at significantly increasing housing delivery. However, the critical role that planning has in facilitating economic growth has been largely overlooked; yet business leaders are increasingly citing planning as holding back their investment.

[1] Indeed, the policy framework on planning for economic development has remained largely unchanged since the first iteration of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) was published in 2012. Produced by a Coalition Government grappling with huge economic problems and a budget deficit worth 5% of national income, the first NPPF was candid:

“the Government is committed to ensuring that the planning system does everything it can to support sustainable economic growth.”[2] (our emphasis)

But times move on – and several versions of the NPPF later – the sense of urgency which characterised that moment in time has arguably been lost. Furthermore, considerable changes have occurred in the economy, many of which have wide-ranging implications for commercial property market drivers, spatial planning and land-use requirements. These include the rapid growth in logistics, booming demand for data centres, gigafactories, creative industries and on-shoring of manufacturing and supply chains.

What are the barriers?

The broad nature of commercial real estate and the range of different industrial and service sectors which occupy it mean that it makes a significant contribution to the national economy. A recent report by Lichfields for the British Property Federation (BPF) estimated in 2023 this amounted to 2.5 million jobs, 5% of total UK economic output, and with £60 bn of capital investment annually.

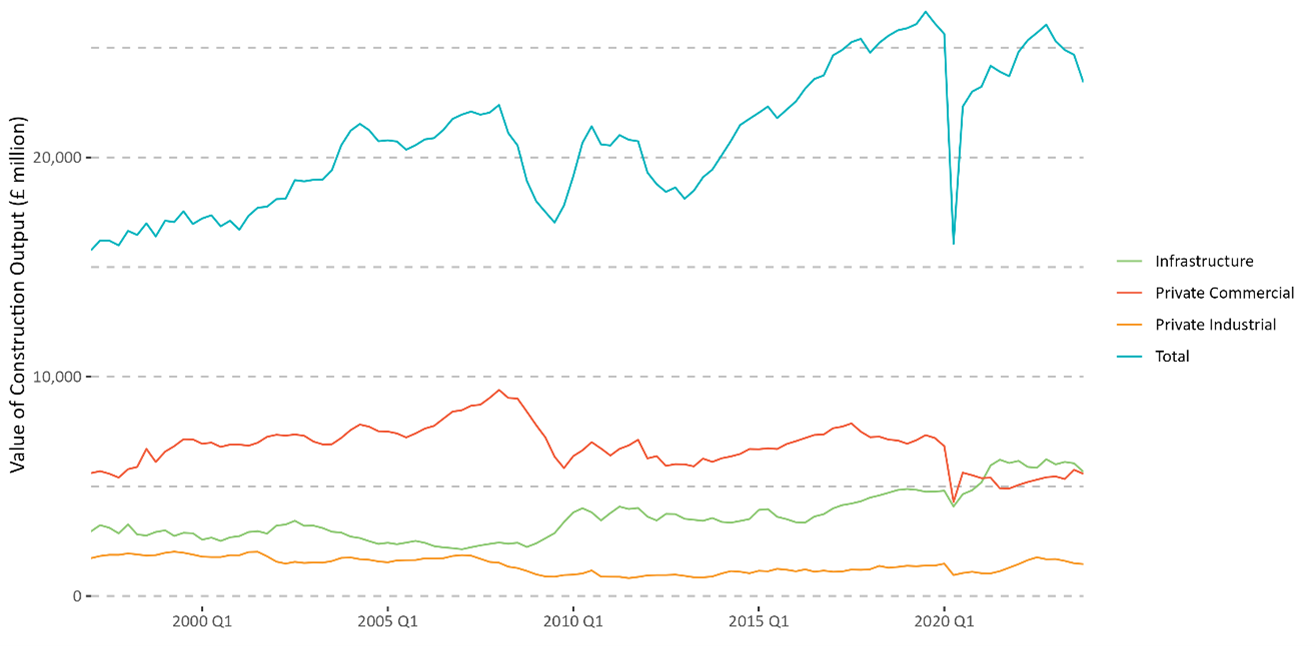

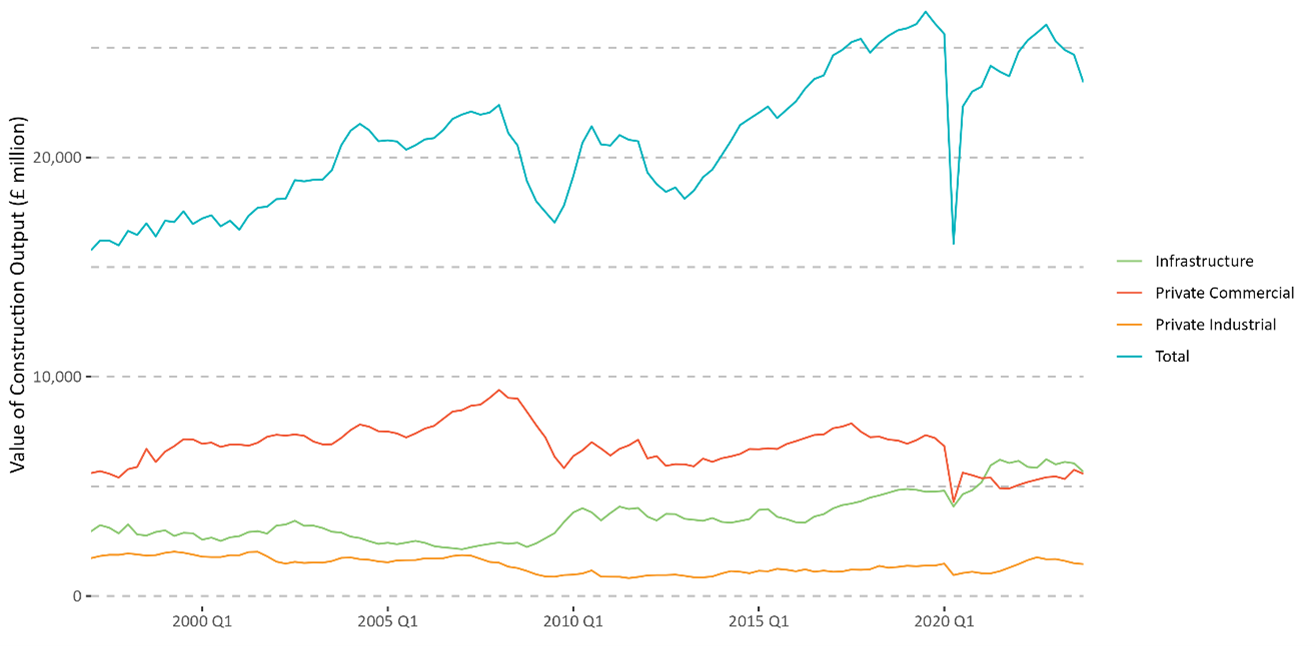

[3]The diversity of the sector means that, relative to some other property sectors (particularly housing), it can be more difficult to measure the impact of planning blockages or under-delivery. Rather the ‘opportunity cost’ is the business investment that is delayed or does not take place at all, and the jobs and economic activity that this could otherwise have created. For example, Figure 1 illustrates that construction output in the private commercial and industrial sectors has been subdued and over time has been flat-lining at best.

Figure 1: Value of Construction Output in England by Sector, 1997-2023

Source: ONS / Lichfields analysis. Note: seasonally adjusted, 2019 prices

At a time of rapid economic and technological change, and set against a competitive market for global investment, the planning system is arguably not sufficiently alive to economic and business needs in spatial and land-use terms. As a bare minimum, planning should perform an enabling role in supporting economic growth through the provision of market-suitable land for uses which support job creation and economic output. It also needs to be agile to respond to rapid economic changes which cannot always be anticipated in local plans which typically look 15 to 20 years ahead, and proactive to provide clear investment signals to businesses.

The absence of an informed and future-facing planning policy framework for economic growth has been compounded by a number of factors including:

-

The slow pace of local plan preparation, holding back the identification of market-suitable land for commercial development.

-

Out-of-date methodologies and guidance to inform planning practice have not kept pace with rapid changes in industry and business needs. For example, techniques used to predict land and property needs which must align with the needs of the new economy and embrace market signals.

-

The effective withdrawal of the national industrial strategy and linked local strategies means that there has not been a clear and consistent mandate to plan for economic sectors and clusters over the lifetime of most recent local plans.

-

A patchwork of place-based planning ‘freedoms’ such as Enterprise Zones, Freeports and Investment Zones have been variable in their application, duration and extent which may have impacted on their main aim of creating or accelerating net additional economic development. Some have been ‘off the shelf’ regeneration projects identified by local authorities rather than necessarily being business or economic need led.

-

The introduction and continued extension of permitted development rights (to residential uses) has gradually eroded controls of many commercial premises and caused some local pressure points on the availability and affordability of business premises at a time when businesses are facing many other cost pressures.

How to turbo-charge growth?

If the political ambitions to rapidly stimulate economic growth are to have any prospect of success, it is clear that some fundamental changes to planning, and linked policy initiatives, will be required to put the system on a growth footing.

We set out below five proposals for how this might happen:

-

Putting in place a clear and up-to-date national industrial strategy, something that Labour has already announced they will do should they form the next government. The merits of ‘top-down’ industrial strategies are often debated, but the reality is that the UK urgently needs a clear blueprint for how it will drive up productivity and meet the needs of priority economic sectors and clusters in different parts of the country.

-

Giving greater weight to economic development including making it a statutory function of local authorities – as the Institute for Economic Development (IED) has been calling for

[4] – and immediately putting in place a presumption in favour of development for economic uses where there is no up-to-date local plan in place. This would also go some way to ensuring a minimum level of resource and budget is provided for economic development functions within local authorities, at a time when many are facing tough budget choices.

-

Updating the NPPF to provide a clear mandate for plan-making and decision-taking on the weight to be attached to economic growth considerations. There is also a need to refresh associated guidance and methodologies so they are primed to support key sectors in line with the national industrial strategy, and allow more flexibility to respond to unforeseen opportunities such as large, bespoke inward investment demand such as the gigafactory facility in Somerset

[5].

-

Reflecting the operational characteristics of business markets, introduce more effective planning for functional economic market areas. For example, a new industrial strategy should provide the economic rationale for a series of new spatial economic development plans which would be driven by business needs and therefore be flexible in terms of geographic coverage (ranging from city-regions to cross-boundary partnerships).

-

Ensuring area-specific economic growth mechanisms are fit for purpose. Current and past governments have had a chequered history when it comes to designating locations for national and international inward investment. However, the principle of having a network of strategic sites across the country that are readily deliverable and attractive to the market remains a sound one. These could offer the flexibility to quickly respond to footloose investment in key sectors. Importantly, such sites need to be embedded in a clear economic rationale and equipped with the necessary infrastructure and delivery mechanisms to achieve their stated growth objectives.

These measures represent a starting point, but the urgent need for planning to play its part in unlocking economic growth cannot be understated. The central challenge for the incoming government is that UK economic growth has now been languishing below trend for some time, and has not achieved sustained annual growth in excess of 2.0% since the 2003-2007 period before the global financial crisis. While it will naturally take time for policy reform to translate into faster growth, it must be at the top of the next government’s in-tray whichever party wins the election.

VIEW MANIFESTO COMPARISON BLOG

[1] ‘Planning the number one growth issue’, CityAM, 17 June 2024

[2] National Planning Policy Statement, March 2012, https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20180608095821/https:/www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policy-framework--2

[3] UK Commercial Real Estate Economic Footprint, Lichfields for British Property Federation, May 2024 https://bpf.org.uk/media/7602/cl16688-01-bpf-economic-footprint-final.pdf

[4] ‘Grow Local, Grow National’, IED manifesto, November 2023, https://ied.co.uk/news_events/grow_local_grow_national_ied_launches_manifesto/

[5] Gravity welcomes Agratas Gigafactory as first site occupier (thisisgravity.co.uk)

Image credit: Matteo Roman via Pexels