The Spring Budget this year felt curiously low key given the continuing speculation (including by some Labour frontbenchers) that an election could be called as early as May. In reality, much of the coverage focused on the absence of any pre-election ‘big bang’ announcement or ‘giveaways’ as had been called for by many Conservative MPs, notwithstanding the second successive cut to National Insurance and further support for families – this time child benefit.

The backdrop provided by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) showed that the overall economic and fiscal outlook is similar to the position at the time of the Autumn Statement in November. While growth has disappointed since then – the so-called ‘technical’ recession – a steeper fall in inflation and interest rates should support a stronger recovery and enable a faster recovery in living standards. Even so, the OBR sees the medium-term economic outlook as remaining challenging.

Despite the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt framing it as a budget for long term growth, this was not a ‘fiscal event’ that centred around planning reform, or signature investments in housing, transport or the built environment to any great extent. Alongside a pitch to the electorate for

economic credibility, much of the Chancellor’s speech was given over to celebrating the allocation of funds to projects and places, perhaps somewhat inevitably in an election year. In this context, it seems that the Government’s focus was on something of a policy ‘spring clean’ – such as allocating funds to projects, publishing new devolution framework agreements, as well as launching and concluding consultations that provide details for ongoing reforms – rather than any bold new policy announcements. Over 40 documents were published alongside the main Budget report.

There were elements that were specifically focussed on development, for example the abolition of multiple dwellings stamp duty relief, and a reduction in the rate of capital gains paid by landlords and second-home owners on home sales, which the BPF has already

warned could hit the build to rent sector. The Budget set out more on the specific ambitions for regeneration and growth across

Leeds,

Cambridge and certain sites in London. Also, a consultation was launched on the proposed design of a new accelerated planning service for commercial projects in England and a review led by Charles Banner KC in to

speeding up the delivery of Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPS).

In place of big investments, the Chancellor focused on the reform of public spending, namely improving efficiencies and productivity in the public sector. The Institute for Fiscal Studies

noted that public services were again facing significant funding cuts in all but health and education sectors, but there is room in the Budget for support to industry investment in skills for local planners. Additionally, digitisation in planning – a key long term goal of this Government – is further fleshed out with a commitment to ‘Piloting the use of AI solutions’ in local plan making a move that is cautiously

welcomed by the RTPI. These are part of a range of reforms aimed at reducing the amount of time public sector workers spend on ‘unnecessary administrative tasks’.

Investment Zones, introduced by former Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng, as part of his ill-fated September 2022 Growth Plan survive albeit now ‘refocussed’ as had been previously announced. The Chancellor used the Budget to highlight the Zones and 12 Freeports already created and setting out the several tax reliefs and business rate retentions that will be offered to the eight IZs across England and four in Wales and Scotland. The Government has announced details on how funding for the English Investment Zones (originally announced in 2023) is to be spent in combined authority’s which have Mayors. There is notably no ‘new money’ attached to this, and the OBR identify it as a policy risk to their forecasts due to it being ‘not yet firm policy’. It therefore remains to be seen what impact the creation of IZs will actually have.

The Government also announced “trailblazer” devolution deals for the North East, as well as deeper deals for the

Greater Manchester and West Midlands Combined Authorities, including a commitment to implement a single funding settlement at the next Spending Review. These single settlements will include central funding falling under five thematic policy areas (‘themes’): local growth and place; local transport; housing and regeneration; adult skills; and buildings’ retrofit.

This is undoubtedly a significant devolutionary move with long term ramifications for these areas. However, with these powers, difficult decisions will also be devolved. The focus on public sector productivity, a looming reduction in public spending, and an ever-increasing demand for public services, all puts significant long term pressure on any discretionary and non-statutory expenditure by local or combined authorities.

In many ways, this Budget continued the Government’s messaging that local areas are being handed the responsibilities to resolve their own financial circumstances. Whilst this is not ‘news’ to those in local planning authorities, the Budget is another reminder that the challenge to local authority financing is a significant threat. A week ago, a

survey of senior council figures found 51% warn their councils are likely to ‘go bust’ in the next parliament unless local government funding is reformed

[1]. It is in this context that the current shift towards devolving powers, without the ability to raise local funds or the prospect of more central government funding support, will leave many local and combined authorities facing tough choices.

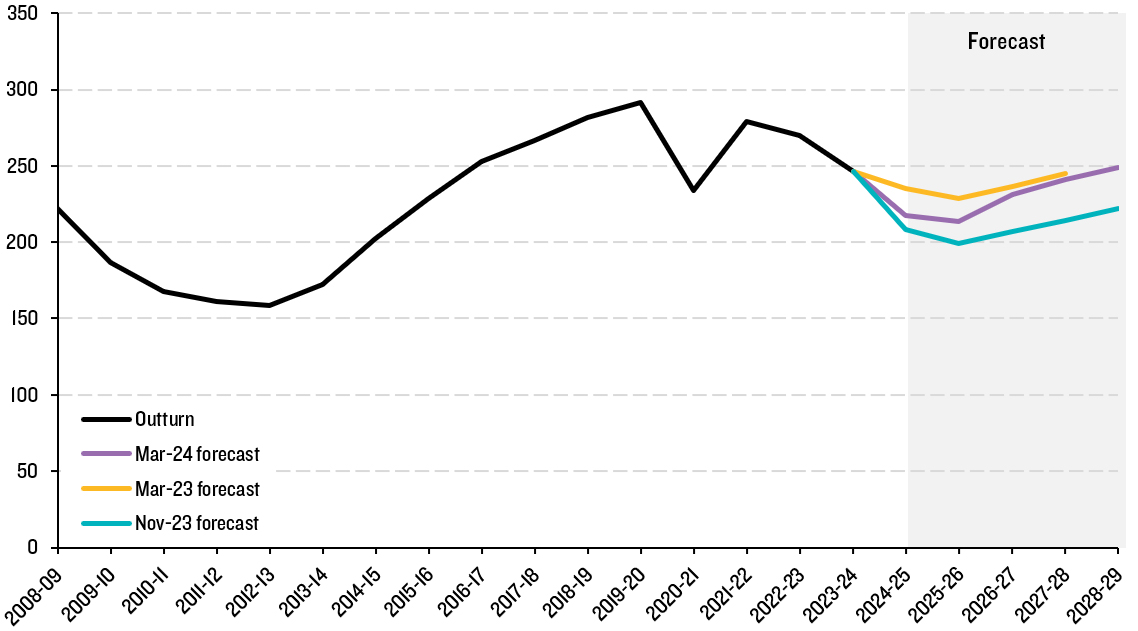

Perhaps one of the most encouraging elements of yesterday’s Budget were improved housebuilding forecasts provided by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). In their latest forecasts for housebuilding, the OBR still expect a major drop in housebuilding activity in the period to 2025/26 to just 213,000 homes per annum, almost a third below what is needed. However, this is a sizeable improvement from November’s projections, with housebuilding forecast to reach 250,000 by 2028/29 (Figure 1).

Fig 1 OBR forecasts of Housebuilding over the last three fiscal events (Net Additional Dwellings)

While it has only been four months since the Autumn Statement, these forecasts reflect greater optimism that inflation and interest rate rises might have peaked. But they also serve as a reminder of the non-policy affects on the housing market that will likely continue to have a large effect on housebuilding rates. The CMA’s Housebuilding market study

final report published last week found:

“The number of houses being built and their affordability are propelled by two key drivers: the nature and operation of the planning system and the limited amount of housing being built outside the speculative approach (such as affordable housing, self-build, and build-to-rent)."

With this in mind, housebuilding rates are likely to be affected by planning reform and policy for the foreseeable future. It remains to be seen whether the OBR forecasts might have to be revisited in light of the negative impacts of the December 2023 NPPF reforms, as indicated by

previous Lichfields analysis.

Taken overall, there were few surprises from the Spring Budget and certainly no ‘rabbits out of the hat’ moments. That was to be expected given it follows an Autumn Statement that was only four months ago, and while the OBR had confirmed a slight improvement in the near term outlook there was really no major change. Added to that was the fact that the Chancellor had limited room for manoeuvre given borrowing is still projected to fall over next five years – with tax as a share of GDP rising to near to a post-war high, debt interest costs falling, and per person spending on public services effectively being held constant in real terms (based on current government plans at least). Yet this low key Budget still contained plenty of signposting on future policy, funding and devolution, and Lichfields will be appraising the implications of these in more detail.

[1] 51% of senior council figures warn their councils are likely to go bust in the next parliament unless local government funding is reformed.