Lichfields is currently monitoring the draft London Plan Examination in Public (EiP), which is scheduled to last until May 2019, and will report on relevant updates as part of a blog series. The fifth blog of the series focuses on the hearing sessions for draft policies E4 – E7 on land for industry, logistics and services, which took place on 19 March 2019.

As the focus of the draft London Plan Examination in Public turned towards the economy and how the Capital should best plan to meet its business needs, the session on land for industry, logistics and services was bound to attract interest. Not least because the draft London Plan policies to more carefully manage the release and re-use of designated industrial land represent one of the most significant changes in policy direction compared with the existing Plan, and because the topic has tangible implications for other sections of the new Plan (most significantly for accommodating housing requirements).

It was good to see a packed panel of representors, comprising a mix of London Boroughs, industrial/logistics developers and operators, and business representative organisations. This ensured an engaging debate, focused around 1) the need for industrial land in London and 2) how to meet the need for industrial land.

Planning effectively for industrial uses in London has become an increasingly complex issue. The backdrop to the Mayor’s proposed new policies is that too much industrial land has been lost to other uses in recent years, exceeding GLA monitoring benchmarks in the majority of Boroughs.

In response, the draft London Plan is determined to make better use of London’s remaining industrial capacity, taking a more stringent approach to future losses of industrial floorspace on policy-protected sites, through a ‘no net loss’ general principle and by assigning refreshed ‘retain’ and ‘release’ categories – and a new ‘provide’ category – to individual Boroughs to better guide the management of remaining industrial land. See Lichfields’ recent

Insight report where the key changes and implications are unpacked in further detail.

The overriding consensus during the hearing session was one of support for the principle of the Mayor’s proposed policies and, in particular, the rationale for protecting precious remaining industrial capacity in the Capital. On detailed matters however, there was a great deal of disagreement and debate over key assumptions that feature in the policies E4-E7, with many participants questioning the ability of the proposed policies to effectively deliver the Mayor’s objective.

In essence, the majority of discussion coalesced around the following key issues and concerns:

1. What are we actually planning for?

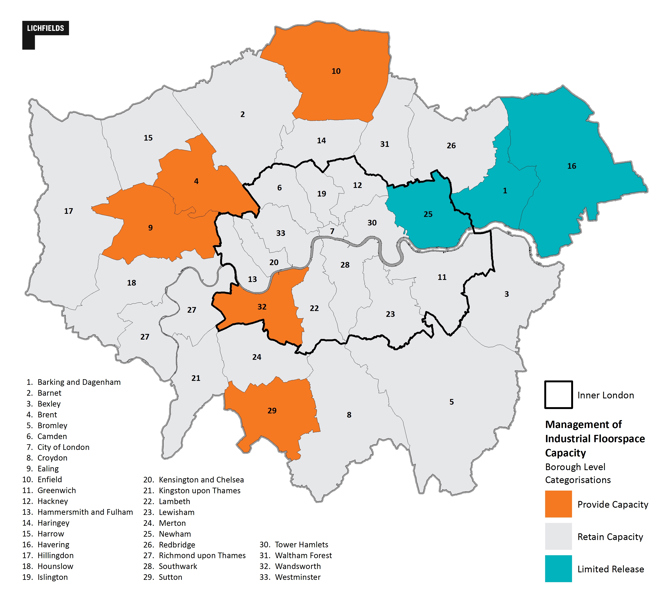

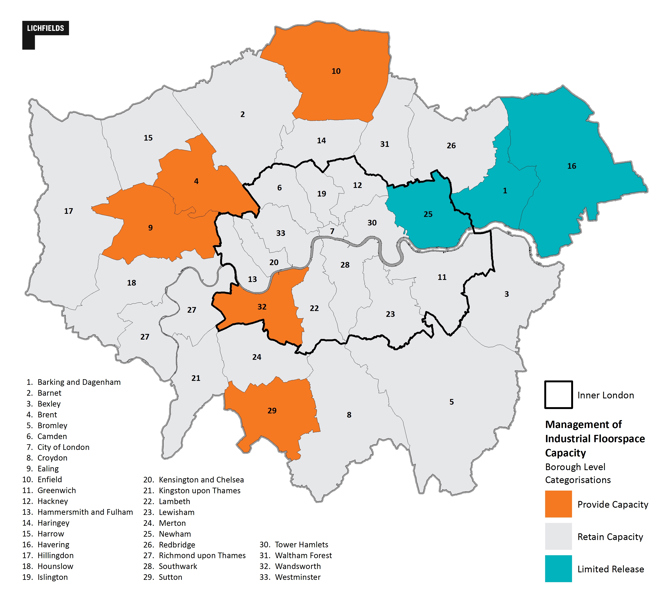

The draft London Plan does not present a specific requirement for industrial floorspace over the life of the Plan, nor set a target for industrial land provision. The GLA says this is intentional, as it does not wish to be “too prescriptive”; however, without an identified requirement, it remains difficult to decipher the overall quantum and scale of industrial space that is being planned for across the Capital – and within individual Boroughs – over the next 25 years. It also makes it tricky to establish a clear logic chain to arrive at the Mayor’s updated Borough-level categorisations for managing industrial capacity (see Figure 1 below). Much confusion was expressed over what the ‘provide capacity’, ‘retain capacity’ and ‘limited release’ categories actually mean in practice, and how they should be translated down into Borough-level development plans.

Figure 1: Managing industrial floorspace capacity – draft London Plan categorisations

Source: Lichfields analysis, drawing on draft London Plan (December 2017)

For instance, as a ‘provide capacity’ borough, Enfield is looking to its green belt for a possible release valve, albeit this is heavily protected by other plan policies (such as proposed policy G2). With industrial intensification failing to date but required by policy, they have had to accept the strong likelihood of under-delivering.

Complicating matters further is a complex supply-side situation, with an apparent lack of clarity over the scale and spatial distribution of ‘pipeline’ industrial land that has already been earmarked for release (for instance through Housing Zones and Opportunity Areas). The GLA acknowledged that a shortfall is highly likely (when demand is compared with supply) but appeared to struggle to quantify or clarify what this shortfall could look like.

2. Intensifying industrial space – is it commercially viable?

The hearing discussions moved onto the principle of intensification (i.e. achieving more intensive and efficient use of industrial land). This is identified by the draft London Plan (and re-iterated by GLA representatives during the session) as the only realistic mechanism or source of supply for accommodating future industrial needs within the Capital, in the absence of ‘new land’ being made available. The draft policies introduce a 65% plot ratio (i.e. ratio of floorspace to land) as a benchmark against which the principle of ‘no net loss’ will be measured. For designated sites to be redeveloped, there would be an expectation that existing on-site floorspace is replaced in full or at a 65% plot ratio – whichever is greater.

The intention may be to prevent developers from ‘gaining the system’, but representors unanimously argued that a 65% blanket ratio is too high, not commercially viable (at single storey level at least) and would act as a significant disincentive to occupiers redeveloping their space for whom a lower plot ratio is operationally critical. Various evidence was cited (including by logistics developer Segro) to suggest that current industrial plot ratios in London typically average more like 45% at best. Lichfields’ own analysis indicates that the current average plot ratio on designated industrial sites in Outer London is currently just 33%, with no sign that intensification is happening at any significant scale, based on industrial floorspace growth trends in Outer London during the past 15 years. Intensification, it was argued, should be recognised as a potentially useful ‘windfall’ source of capacity, but not the primary strategy for meeting future needs.

In response to these concerns, the Mayor has proposed a suggested change to Policy E4 to reflect the fact that some industrial uses require significant yard and servicing space, so that “in some instances, this may provide exceptional justification for a plot ratio that is lower than 65 per cent on development for industrial uses only”. A welcome flexibility, albeit the GLA is keen to retain its statement of intent.

Participants also pointed out the potential planning issues that could pose unintended consequences from industrial intensification, including pressure on roads/highways capacity and parking, unless the necessary infrastructure upgrades are implemented in parallel.

3. Non-designated sites – time to protect?

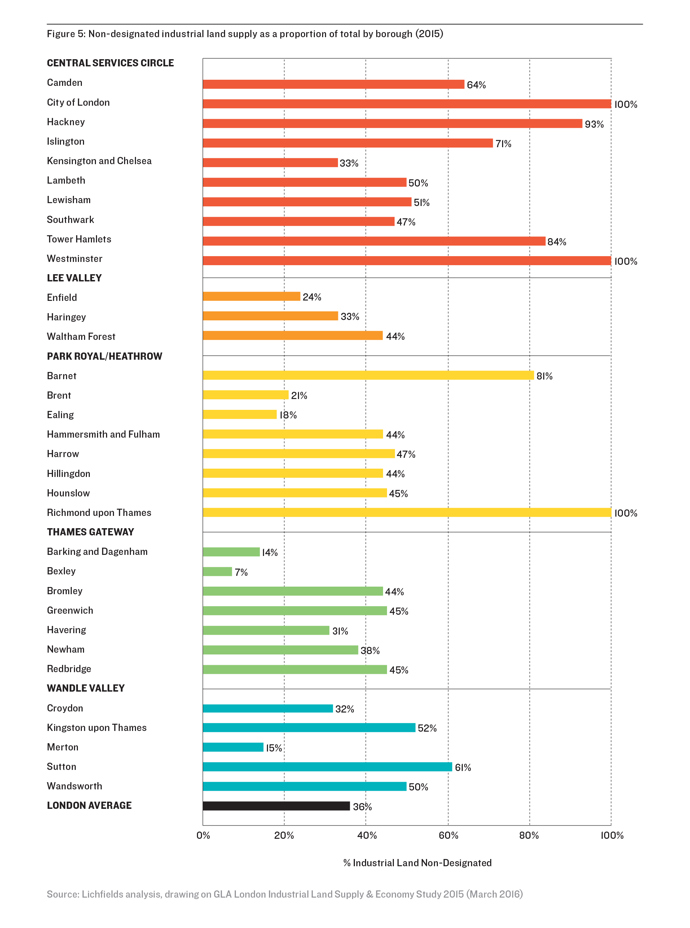

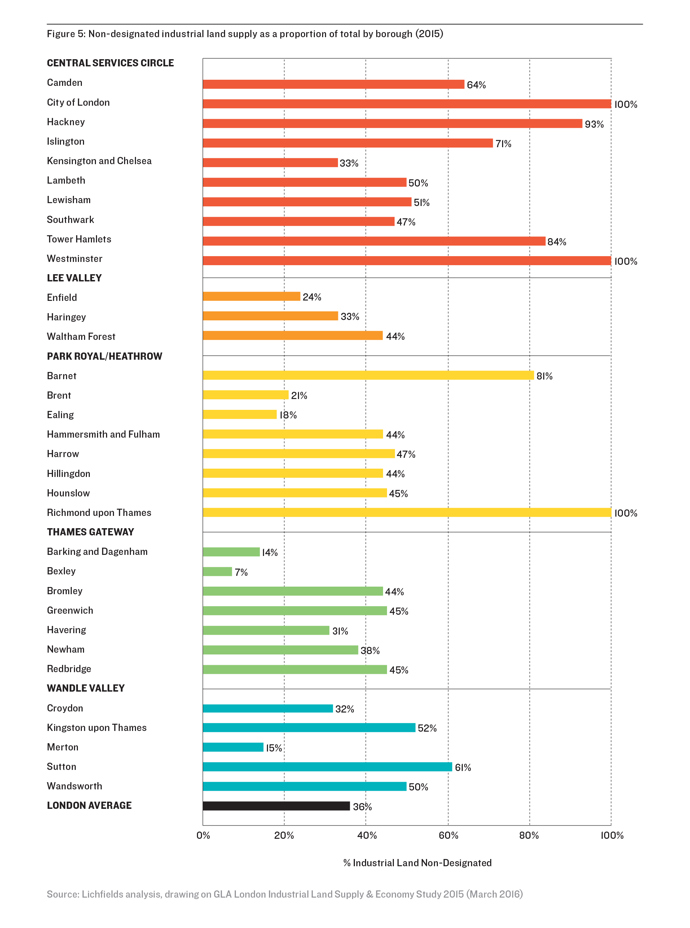

Alongside a more concerted effort to encourage more efficient use of existing sites, the draft London Plan’s shift in policy approach may also require London boroughs to re-visit and re-consider how much formal protection should be given to currently un-designated industrial sites. These make up more than a third of London’s industrial land (36%) and remain particularly susceptible to future release. Our recent analysis suggests that pressures are likely to be most acute in Central Services Circle Boroughs where the current level of protection is weakest (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Non-designated industrial land supply as a proportion of total by borough (2015)

Source: Lichfields analysis, drawing on GLA London Industrial Land Supply & Economy Study 2015 (March 2016)

The GLA were keen to stress that individual Boroughs are free to apply more specific protection to these non-designated sites through the local planning process, if they choose to, although various representors at the hearing session called for more strategic level protection, and clearer guidance, given the crucial role in cumulative terms they are expected to play in accommodating the Capital’s industrial activity going forward.

4. How will the bolder approach be monitored and enforced?

Another key area of concern discussed at the hearing session was the process of monitoring future change and progress against the draft London Plan’s stricter policies, and how this would work in practice.

The past two decades have shown that policies designed to protect and manage the Capital’s industrial land have proved less than effective. Accordingly, it is clear that a more stringent approach to future losses of industrial floorspace on policy-protected sites will necessitate a more sophisticated, regular and comprehensive system on the GLA’s part to monitor floorspace change; on an annual basis, on a site-by-site basis and by comparing against the updated ‘land release benchmarks’ and Borough-level categorisations.

Until further detail is shared by the GLA on precisely how the ‘no overall net loss’ principle will be monitored and enforced ‘in real time’, question marks will remain over just how effective the proposed London Plan’s bold new approach to planning for the Capital’s industrial land needs can be.

This all left little time to discuss some of the other pertinent issues raised by the Mayor’s proposed policies E4-E7, such as the practicalities of a masterplanning approach to Strategic Industrial Land/Locally Significant Industrial Sites intensification and consolidation, and the scope for ‘substituting’ some of London’s industrial capacity to locations in the wider South East where it offers mutual advantage and makes economic sense.

Overall, the challenge facing the Mayor to balance the various pressures of competing land uses and development needs across a thriving Capital was borne out particularly starkly in this hearing session. The Mayor seems resolute in ensuring that industrial land is no longer considered an ‘easy target’, but there appears to be some way to go to convince both individual boroughs and the development sector that his preferred approach will actually deliver.