Last month’s London Plan

Panel Report confirms what was widely suspected – that London’s future industrial land needs are probably higher than first thought, mainly because of growth in demand for storage and warehousing within and close to urban locations. Whilst the evidence indicates a modest reduction in the amount of land needed for manufacturing uses (c.170 ha), this is more than counterbalanced by predicted growth of land needed for distribution uses (c.280-400 ha), driven by a combination of London’s population growth and the shift to online retailing and e-fulfilment centres.

The draft Plan assumes achieving a 65% plot ratio average to accommodate the future balance of industrial needs. But evidence submitted to the Examination pointed to this being challenging (indeed, our

research last year across a sample of sites in Outer London found the current average ratio closer to 33%), and not necessarily applicable in all cases. This led the Panel to conclude,

“whilst this does not mean that the average of 65% could not be achieved in the future, it does suggest it may be challenging in some locations and for some types of development.” In other words, intensification of industrial land is not in itself likely to absorb the full level of industrial land needs identified, and in any event there is uncertainty about how deliverable this would be in practice.

To complicate matters, the pipeline of industrial land release is also now much greater than was originally assumed. In 2015 about 12% of existing industrial land, equating to 838ha, either had planning permission for non-industrial development or had been identified by boroughs has having potential for redevelopment, with no certainty that any industrial capacity would be retained. The 2017 SHLAA indicated that this figure had increased by 106ha to 944ha, implying that future losses of industrial land will probably be higher than was first thought – much to help meet the Plan’s housing requirements.

Furthermore, the Panel noted that the vacancy rate of existing industrial land and premises in most boroughs is less than 5% – referred to as “a reasonable benchmark to assume in an efficiently operating market” – so there’s not even much slack within the current land supply to provide more capacity (apart from a small number of east London boroughs where vacant supply is potentially higher).

Taken together, these factors led the Panel to report, “there is likely to be a need, in quantitative terms, for more industrial land to meet future demand over the plan period to 2041 than assumed in the Plan.” However, it’s not just a quantitative issue. Whilst existing industrial land supply may be distributed across property markets and in locations that are generally suitable for the types of industrial use that are expected, the Panel also identified that there will almost certainly be a need to meet new locational and site specific requirements of some businesses including in and around the CAZ and other accessible locations. So not only does London need more industrial land, but it needs to broaden the portfolio of sites and locations it has to offer.

In this context, the Panel concluded:

“We consider that the approach to meeting [industrial land] needs set out in E4 to E7 is aspirational but may not be realistic. This is for a number of reasons relating to the practicalities and viability of significant intensification of SIL and LSIS, the continuing pressure to redevelop non-designated sites for other uses, and the likely need for new sites in certain locations, including in and around the CAZ.”

There was significant debate about the policy detail at the hearing sessions in March, as we reported in an earlier

blog. Modifications are suggested to help the effectiveness of these policies E4 to E7 in the short to medium term, but the Panel is unequivocal that planning for medium to longer term industrial land needs should fall within the remit of the future strategic, London-wide Green Belt review that is recommended.

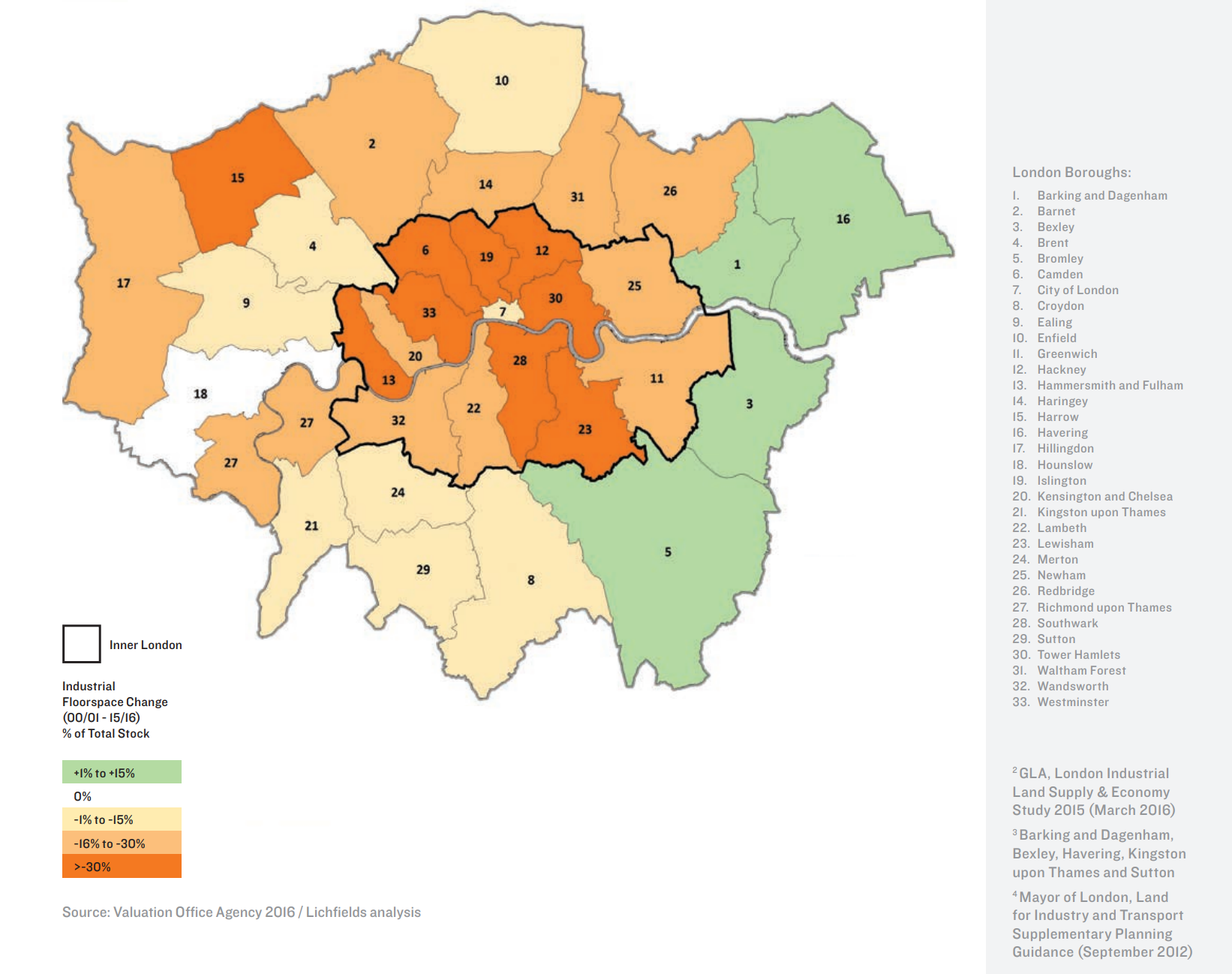

The context for this is that in the 15 years since the first London Plan was adopted, there has been a general presumption in favour of industrial land release across London within specified benchmarks. However those benchmarks were significantly exceeded, with the end result being far greater release of industrial land than was ever anticipated (Figure 1). The effect of this has been not only to reduce London’s industrial capacity beyond what structural trends allowed for, but also to narrow the range of industrial locations (particularly within inner London) available to accommodate the wide range of business uses that can exist on industrial sites.

Figure 1: Change in London’s industrial floorspace supply (2000-2016)

In response, the draft Plan proposes a far more stringent approach to better guide the management of remaining industrial capacity, but relies heavily on intensification and co-location of industrial uses (plus introduces – but doesn’t really articulate in any detail – the concept of ‘substitution’ whereby industrial needs could be met outside of London). However, the Panel was evidently not convinced that the capital’s current and likely future demand-supply balance for industrial land could be met solely in this way, and indicates a bolder approach is called for in the longer-term. The risk is that the issue simply ends up in the long grass, whilst in the meantime a buoyant industrial market adds more pressure. It will be interesting to see how the Mayor responds.

See our other blogs in this series:

Lichfields will publish further analysis on the London Plan Panel Report and its implications in due course.

Click here to subscribe for updates.