Boris Johnson has wasted no time in setting to work on his election pledge to increase investment in the North of England and Midlands, in a bid to boost economic growth and prosperity within some key first-time Tory constituencies.

As widely reported by the press over the Christmas break, it is understood that HM Treasury could make wholesale changes to the way in which public investment is allocated to key economic growth interventions across the country, with value for money and economic appraisal assessments (as guided by the Treasury’s ‘

Green Book’ guidance for nearly half a century) recast to focus explicitly on boosting economic wellbeing in the North and Midlands.

This could affect future national government investment decisions in a range of transport, infrastructure and business growth projects, shifting the focus away from national economic growth outcomes (and overall scale of economic benefit) towards reducing inequality and the ‘productivity gap’ between northern and southern England.

Further detail is expected in the Spring Budget – but on the face of it, these proposals could have a significant impact upon the spatial distribution of government resources and funding available to stimulate and encourage economic growth.

The economic (and political) rationale is clear. The UK’s ‘economic divide’ – the disparity between the least and most productive parts of the country – is growing according to the latest regional output

data released by ONS in December.

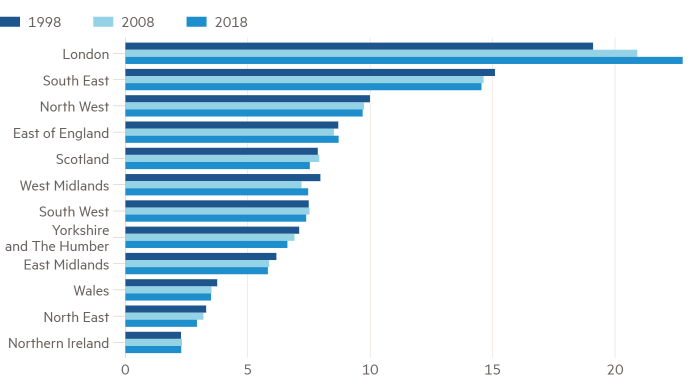

The data shows that the gap in productivity (measured in terms of economic output or GDP per person) between the UK’s richest region (London) and the poorest (North East) widened last year, and that London’s share of, or contribution to, the national economy has increased at the expense of other regions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of UK GDP at current prices

Source: Financial Times Online, based on data from ONS

The statistics underline the scale of the productivity challenge facing the new Conservative government, which prompted publication of the

UK Industrial Strategy just over two years ago. This calls for all parts of the country to boost their economic contribution to UK plc, by drawing on their distinctive economic strengths, competitive advantages and growth opportunities (as summarised in a

previous Lichfields blog).

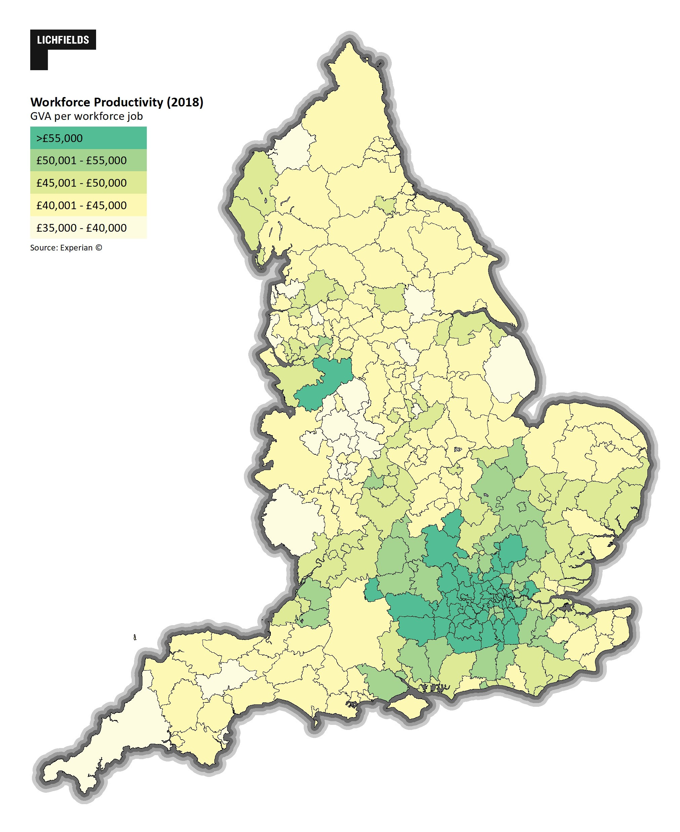

UK regional inequality is amongst the worst in the developed world and is a problem that successive governments have been grappling with for many years. Stark disparities in economic performance across the country, as shown in the map below, have become a familiar trend.

Figure 2: Workforce productivity by local authority in England (2018)

Source: Experian 2019 / Lichfields analysis

Rightly then, the issue has been attracting increasing political attention over recent months and years, reinforced by the work of independent initiatives such as the

UK2027 Commission, which calls for a long-term plan to tackle regional inequality and a national renewal fund along the lines of Germany’s East-West reunification strategy. Commission Chair Lord Kerslake’s keynote address at the recent Institute of Economic Development Conference referred to the UK being at a ‘turning point’. The Commission’s

First Report published last year described previous government action to tackle inequalities across the UK as underpowered ‘pea shooter’ and ‘sticking plaster’ policies – too little and too short-lived. The report argues that if we are really to shift the dial on spatial inequalities, what we require for the future will need to be, “structural, generational, interlocking and at scale”.

This begs the question: can the deliberate targeting of public investment away from London and the wider South East in itself help to bring about or instigate the structural shift needed? The proposals will no doubt be welcomed by many, but arguably need to be accompanied by a more holistic policy framework that is clear about how each part of the UK can play a complementary role in driving forward productivity improvements and genuinely inclusive growth.

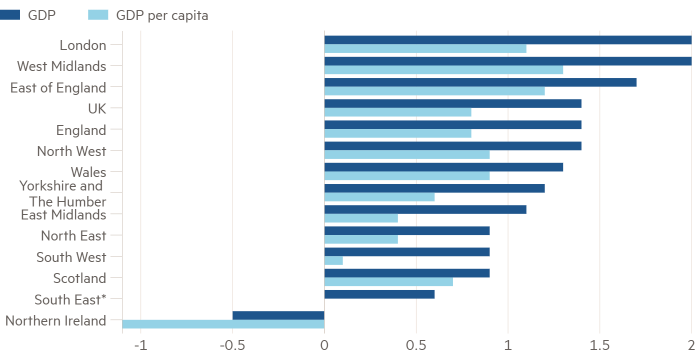

Indeed, the latest ONS output statistics identify some concerning trends within parts of the country that have traditionally performed well, such as the South East region which recorded zero per capita growth last year (Figure 3). The South West also recorded sluggish levels of growth, while the West Midlands (an area that could benefit from this ‘rebalancing’ investment) outstripped London in terms of per capita growth. There are also significant disparities within regions that can be obscured through use of broad regional measures, for example the presence of deprived coastal communities in the South East. As ever, there are clearly some spatial nuances at play.

Figure 3: Annual % change in output by region (2018)

Source: Financial Times Online, based on data from ONS

We can expect a lot more coverage and comment on this topic between now and the Spring Budget, where the devil may well be in the detail.