So, the wait is over – the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework [GMSF] Publication Draft Plan was approved by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority [GMCA] on the 30th October 2020. Subject to approval by the 10 constituent authorities through November, the consultation on GMSF 2020 will begin on 1st December 2020 and will run for only 8 weeks, ending on 26th January 2021.

There is a lot to cover on the GMSF and Lichfields is drafting a series of blogs covering particular topics. For a general summary see Brian O'Connor's

GMSF in a nutshell blog. This Blog focuses on the perennially hot topic of housing.

The updated GMSF has been awaited with great anticipation amongst the development community. It will set out the approach to housing land across all ten Greater Manchester [GM] authorities for the next 17 years. In recent weeks leaked documents, local newspaper headlines and e-newsletters has further dampened expectations amongst the development sector, suggesting that the GMSF was intending to go no further than the bare minimum LHN figures, further reducing the need for Green Belt release.

For those that have not read in full the previous iterations, from a housing perspective, the GMSF 2020:

- sets out how Greater Manchester should develop up to the year 2037;

- identifies the amount of new housing development that will come forward across the GM 10 districts;

- identifies the main areas in which housing will be focused;

- allocates sites for housing outside of the urban area; and,

- defines a new Green Belt boundary for Greater Manchester.

The GMSF 2020 is full of fine words which set out aspirations for growth, delivery, and the role of Manchester as a city in a world stage, including meeting (just) identified needs for market and affordable housing.

The questions remain as to whether this rhetoric can be matched by substance (including the evidence base that underpins it). To what extent has the detail been driven by political influences, with a desire to protect Green Belt and limit housing numbers, hamstrung the GMSF 2020?

Scale of housing need

Policy GM-H 1 of the GMSF 2020 sets a minimum target of 179,078 net additional dwellings over the Plan period 2020-37 at an annual average of 10,534 dpa. This is below the previous revised draft GMSF target of 200,980 new homes over a slightly longer period of 2018-2037 (or 10,578 dwellings per annum (dpa)). Even this figure was reduced by 7% from the 2016 draft, which required the delivery of 227,200 new homes over a 20-year period (11,360 dpa).

The previous (lower) targets have been pursued in the knowledge that it would result in the City Region losing the £68m housing deal that was tied to the GMSF’s original target of 227,200 homes.

The latest 10,534 dpa target is based on the Government’s current standard methodology [SM] for calculating local housing need [LHN], which uses the 2014-based household projections with an affordability uplift. As an initial starting point, this is correct; albeit the governments consultation on a future alternative SM need to be remembered. However, this figure represents only the starting point for identifying housing need. The GMCA does not seem to have had appropriate regard to other issues that could justify a higher figure (even if it were only to discount them).

The Government is clear that the figure derived by the LHN target is intended to be a minimum; and provides Guidance that sets out the circumstances whereby a higher figure might be considered. This is because the standard method does not attempt to predict the impact that future national or local government policies e.g. Northern Powerhouse aspirations (they are Policy Off). Nor does it account for changing economic circumstances (e.g. arising from the Covid-19 pandemic), or other factors that might impact demographic behaviour.

The GMSF address this point very briefly in paragraph 1.33:

“Government has been very clear that deviation from the standard methodology can only be justified in ‘exceptional circumstances’. No exceptional circumstances have been identified to justify deviation from the standard methodology in GMSF 2020.”

However, no explanation or analysis is provided by the GMCA as to why this conclusion is valid, and it does not appear to have been tested at all in the accompanying Strategic Housing Market Assessment [SHMA]. This appears to be a major omission.

Section 8 of the accompanying GMSF 2020 Growth and Spatial Options Paper did assess 3 potential growth options against the GMSF Vision and the GMSF Strategic Objectives. The higher growth option considered the delivery of 227,000 new homes compared to the 179,090 derived from the LHN calculation.

However, whilst the Paper concluded that the LHN Option 2 was its preferred option, this seems to be on the basis of balancing a range of a policy considerations concerning social, environmental and economic opportunities (hence the higher growth option is criticised for “

providing more land than is needed to meet GMs housing and employment needs could put more pressure on GM’s environment and could hinder activity in relation to climate change and air pollution”). This is a different (and subsequent) exercise

[1] from an exceptional circumstances test examining the deliverability of growth strategies, economic alignment or the impact of strategic infrastructure.

On the face of it, if exceptional circumstances to increase the housing target above the LHN do not apply to Greater Manchester, it is difficult to see where they would apply anywhere else in Northern England.

For example, as the GMSF itself states:

“The strength and strategic location of Greater Manchester puts it in an ideal place to act as the primary driver for the Northern Powerhouse... …Hence it will be important to deliver relatively high levels of growth within Greater Manchester for the wider benefit of the North.” [para 2.25]

If Greater Manchester, the key driver of the Northern Powerhouse, which is essential to the Government’s north/south “Levelling Up” agenda, cannot stir itself to accelerate housing delivery and construction above the bare minimum, then where else do we turn? In this context, aspirations for Greater Manchester to be a ‘top global city’ by the end of the plan period with similar economic indices as London and New York (para 2.19) ring hollow.

Similarly, the GSMF rightly acknowledges the considerable benefits of HS2:

“which will help to deliver a more integrated national economy, opening up much greater business opportunities to support UK growth… ensuring that people are well connected to the new homes and job opportunities that these investments offer” [paragraph 2.23]

This sounds an awful lot like the “

strategic infrastructure improvements that are likely to drive an increase in the homes needed locally” that Government clearly indicates

[2] should be one of the exceptional circumstances justifying a departure from the SM.

Spatial distribution

The Plan directs the bulk of housing towards what it considers to be the most sustainable areas – primarily brownfield sites within the city and town centres. The GMSF refers to the “Inner Area Regeneration of those parts of Manchester, Salford and Trafford surrounding the Core Growth Area. Together with the Core Growth Area, around 40% of overall housing supply is found here.” [para 1.24, bullet 1]. In practice, this means a wholesale redistribution of housing requirements from the southern districts to Manchester, Salford and the Northern parts of the conurbation. Regarding the latter, the GMSF aims to boost “the competitiveness of the northern districts – addressing the disparities by the provision of significant new employment opportunities and supporting infrastructure and a commitment that collectively the northern districts meet their own local housing need.” [para 1.24, bullet 3].

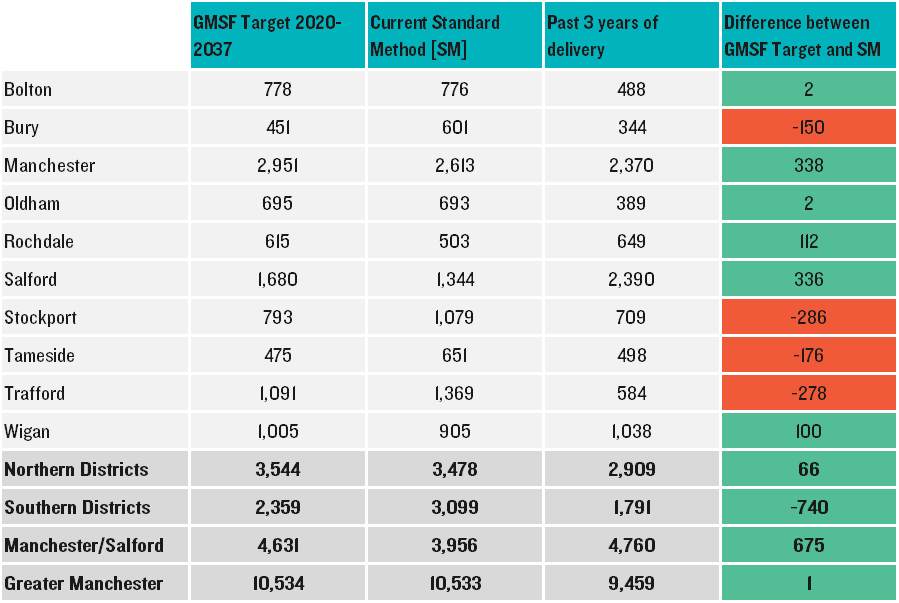

So what does this mean in practice? As before, the GMCA has not distributed housing need across the districts as per the SM, but has instead redistributed the housing allocations based on policy objectives. As summarised in Table 1.1, there are some very clear ‘winners and losers’ in the GMCA’s approach.

Stockport, Trafford and Tameside see a reduction of 740 dpa collectively, with both Tameside and Stockport seeing a reduction of around 27% based on the SM calculation.

This ‘need’ is predominantly redirected towards Salford and Manchester, which increase by 675 dpa. The redistribution to the northern districts is centred entirely around Rochdale and Wigan, with Bolton and Oldham essentially meeting their own needs. In fact, Bury’s target is a substantial 150 dpa below its SM-derived need, a fall of a quarter. This would seem to fly in the face of the GMCA’s goal of ensuring that higher levels of growth will be focused in northern Manchester and that they will “meet their own needs”.

Table 1.1 Distribution of Housing Need Across Greater Manchester

Source: GMCA (2020): GMSF Publication Draft 2020, Table 7.2 / Lichfields’ Analysis

The GMSF suggests that higher levels of housing growth being focused in the central and northern districts of Greater Manchester will assist in “achieving a more balanced pattern of growth across Greater Manchester and a better distribution of skilled workers to support local economies, helping to reduce disparities.” [para 7.15]

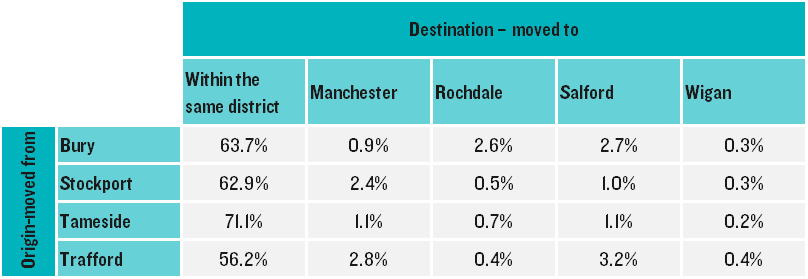

This of course assumes that people wishing to live in south Manchester would just as readily move to the Regional Centre, Wigan or Rochdale to meet their housing needs, when GMCA’s own evidence clearly demonstrates that GM is not a self-contained Housing Market Area. Table 2.1 of the GMCA’s SHMA Update 2020 makes it abundantly clear that none of the 4 districts that are poised to see a big reduction in their housing target, have a strong relationship with the 4 Central/northern districts that will take on board their shortfall. So, for example, 71 out of 100 house moves in Tameside took place within the same local area in the year to 2011, compared to only 3 out of every 100 moves being from Tameside to Manchester, Rochdale, Salford or Wigan. Wigan in particular has almost no inter-relationships with the other districts and appears to be a separate housing market in itself.

Table 1.2 Proportion of moves to Greater Manchester districts from England and Wales, 2011

Source: GMCA (2020): SHMA Update, Table 2.1

The effect of this will be felt by future generations with worsening affordability in the south as house prices continue to be driven up by suppressed supply. That supressed supply provides limited opportunity to provide more affordable housing. A virtuous circle creating a social and economic timebomb for future generations. Moving on to affordability specifically, this is rightly identified as a key issue:

“a key challenge and priority for Greater Manchester is to ensure that new housing comes forward at a price that potential occupiers can afford.” [para 7.21]

The Government is also acutely aware of the problems caused by housing affordability, and it is one of the key components of its SM for calculating housing need. Its current proposals for a new, nationally-determined and binding housing requirement “

would be focused on areas where affordability pressure is highest to stop land supply being a barrier to enough homes being built.”

[3] However, the GMSF 2020’s approach is to do precisely the opposite, redistributing housing need away from those areas with the most significant affordability problems and towards areas where housing is already comparatively affordable.

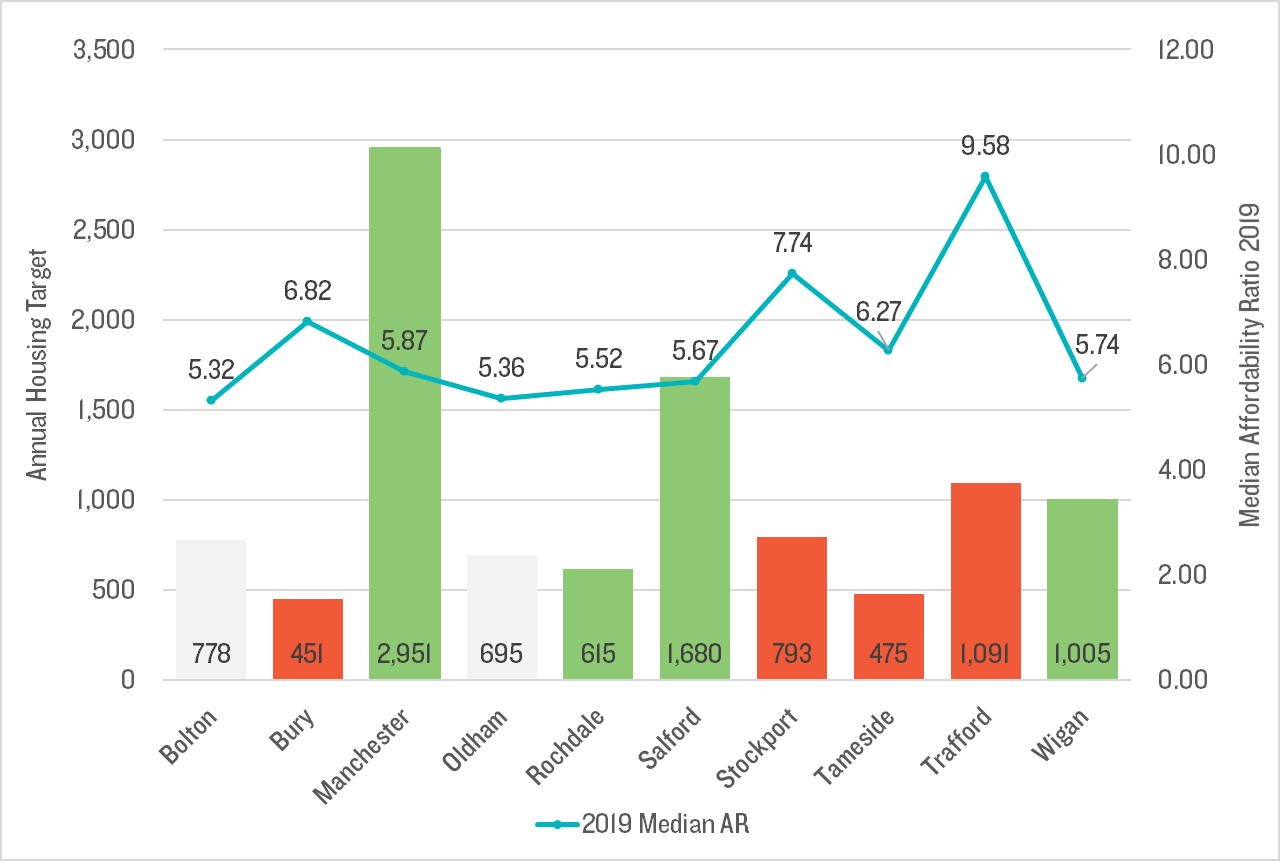

As we can see from Figure 1.3, the areas that are least affordable are also the areas that the GCMA considers should have the highest cuts in their housing targets. So, the 4 bars in the Figure below highlighted red (Bury, Stockport, Tameside and Trafford), which have GMSF targets below the SM identified need, are also the 4 districts that have the highest median affordability ratio (workplace-based).

Indeed, Trafford’s median affordability ratio is as high as 9.58, which is the highest of any district in the whole of northern England (comprising 72 districts). Observers may struggle to reconcile this with the rather complacent comment in paragraph 7.21 of the GMSF 2020 that: “Overall, Greater Manchester is a relatively affordable place to live on average compared to some other parts of the UK, particularly London and the South.”

Figure 1.3 Comparison of Affordability Ratios and proposed GMSF Housing Targets

Source: Lichfields / ONS. Green bar denotes a GMSF housing target that is above the SM need; a red bar denotes a GMSF target below the SM need; and a grey bar denotes that the two targets are broadly in alignment.

The type of homes to be provided

A key part of the overall strategy is to maximise the amount of development on brownfield sites in the most accessible locations and minimise the loss of greenfield and Green Belt land as far as possible. In this regard, the GMSF 2020 states that “in order to deliver the necessary densities, an increasing proportion of new dwellings will be in the form of apartments and town houses, continuing recent trends” [para 7.30]. The GMSF 2020 goes on to say that “there is scope to increase the number of families living in apartments, especially if higher density neighbourhoods can be made more inclusive for all age groups.” [para 7.31]

As a result, Table 7.3 of the GMSF 2020 identifies that 58% of all the residential land supply to 2037 comprises apartments. This is a huge amount and fails to address the significant need for family housing in GM. Whilst the delivery of apartments and the efficient use of space for housing are clearly important considerations, the current pandemic has thrown into sharp relief people’s basic desire for access to private outdoor areas, preferably a garden, and, increasingly, to live in a property that is going to give them the additional space that would allow them to work from home on a regular basis.

Furthermore, the Council’s own evidence suggests that high density schemes tend to be less viable and struggle to provide the supporting infrastructure (including affordable housing) necessary for sustainable communities. As set out in the GMCA’s GM Strategic Viability Report:

“in the city centres the higher density schemes, generally come forward with PRS and have little or no affordable housing due to viability concerns.” [page 52]

There is a lack of any explanation as to how education, health and recreation infrastructure could be provided in the City Centre to support such high-density apartment developments that will presumably have to accommodate large numbers of children.

Supply

Table 7.1 sets out that in numerical terms, the existing supply of potential housing sites identified in the districts' strategic housing land availability assessments [SHLAAs], small sites and empty properties is adequate to meet the overall identified need, and that the additional 24,472 GMSF 2020 Green Belt allocations would result in an overall supply of 208,925. This is 16.7% higher than the SM target over the 17 year plan period.

Whilst any flexibility in supply is welcome, there is considerable uncertainty over whether the 176,665 homes identified in these SHLAAs, plus another 7,788 of windfall allowances, will really come forward as planned. For example, from an initial review of the accompanying Housing Land supply tables, it appears that at least 64,000 units included in the Table (40% of the total) do not have any extant planning permission in place, nor are they allocated in an adopted Plan. It therefore seems ambitious to assume that all of these will come forward over the plan period.

The GMCA also seem to be suggesting that many of these sites are not viable at present, and will be difficult to deliver without substantial public sector intervention – “Many of these sites therefore face challenges which will need assistance to kick-start their delivery” [para 7.17].

The GMSF also argues that GM needs to identify a phasing trajectory which it considers is realistic and which will result in housing being delivered as planned over the life of the plan. This is due to the uncertainties over Covid-19, but also because “a significant proportion of the land supply in the early years of the plan is made up from sites within the urban area, the majority of which are on previously developed land. Many of these sites therefore face challenges which will need assistance to kick-start their delivery” [para 7.17].

The upshot of this is that the annual average delivery is reduced from 10,534 dpa to just 8,498 dpa in the first 5 years of the plan to 2025, with the shortfall being met at the back end of the plan period. As a result, and according to Table 7.2, this means that Tameside’s annual target for the first 5 years, which has already been arbitrarily reduced from 651 dpa to 475 dpa, actually falls to just 281 dpa between 2020-2025 – a 57% drop on its actual needs. Similarly, Trafford, which has an SM need of 1,369 dpa reduced to a GMSF annual target of 1,091 dpa, would only have to deliver 591 dpa for the first 5 years – a fall of 778 dpa on its actual need in the most unaffordable location in northern England. This will undoubtedly leave many households having to move elsewhere to meet their housing needs.

Affordable housing delivery

The viability point also has serious repercussions for the delivery of affordable housing in GM.

The GMSF recognizes that “Greater Manchester is facing a housing crisis...The increase in rough sleeping over recent years has been the most visible manifestation of this, but lying behind it is a much more extensive problem of many people being unable to access suitable housing at an affordable price and with certainty of tenure. Over 99,000 people are on the local authority housing waiting lists in Greater Manchester. A lack of appropriate housing options prevents some people from forming their own households, particularly younger adults, whilst those who can may have to cope with substandard or expensive accommodation.” [para 7.2]

This is an important point, and one that has doubtless led to the ‘aspiration’ to “deliver at least 50,000 additional affordable homes across Greater Manchester up to 2037, with at least 30,000 being for social rent or affordable rent”. [Policy GM-H-2]

However, to deliver 50,000 affordable homes out of a target of 179,090, this means that around 28% of all dwellings delivered will need to be for some form of social housing.

The GMCA’s GMSF Strategic Viability Report Stage 1 (September 2020) makes sobering reading in this regard. It states that: “When affordable housing is introduced to the typologies tested (up to 20% as a mix of affordable rent and shared ownership) most typologies were found to be viable within VA1 -VA3. However, typologies tested in VA4 and VA5, cannot afford to deliver any affordable housing using the current assumptions.”

So even in the higher value areas of southern GM, affordable housing was only tested at 20% of overall delivery. In the weaker housing market areas, which cover large swathes of northern GM, much of Manchester City and almost all of Tameside, no affordable housing is viable at all. Given that many of these areas are expected to accommodate the bulk of the GSMF’s housing sites, this conclusion cannot be reconciled with an ambition for 50,000 affordable homes – it appears fundamentally undeliverable based on the housing strategy at present.

The fact that apparently 144,221 dwellings will come forward on often complex previously developed land (Table 7.1) further weakens the GCMA’s viability argument.

Conclusion

Whilst we welcome the arrival of the latest draft of the GMSF following a substantial hiatus, there is much to be concerned about regarding its practical deliverability. Some components of the overall strategy, of seeking to improve affordability, making best use of brownfield land and providing greater flexibility in the housing land supply, are to be welcomed. Whilst we are of course living in unprecedented times with considerable uncertainty regarding the strength of the economy, how it will impact on the housing market in the short and long term, and how (and when) the development industry will fully recover. However, it has to be said that the strategy followed, of redirecting development to selected northern districts and particularly the Regional Centre in high density apartment blocks appears a very risky one that does not seem to align well with existing needs and an increased shift towards home-working in the outer suburbs.

The GMCA appear willing to forego GM’s leadership role at the heartbeat of the Northern Powerhouse just as they were prepared to lose the £68 million housing deal by targeting a lower housing target and less contentious levels of Green Belt release. As a result, we are faced with a situation that the least affordable parts of Greater Manchester will see levels of housing provision that are significantly below their actual need. Furthermore, that need will be pushed back to the later years of the plan, after 2030. Housing supply is shifted to the Regional Centre, Wigan and Rochdale, which have very limited relationships with Trafford, Stockport and Tameside. Family housing will be replaced with high density apartment blocks, often in some of the least viable parts of the conurbation, and much of it for PRS. This means that affordable housing targets cannot be met, nor community infrastructure delivered. It is difficult to see how this can be reconciled with the ambition expressed in the document for Greater Manchester to become a ‘global city’ on a par with London and New York.

[1] The exercise set out in the Growth and Spatial Options Paper forms a subsequent stage in the analysis after the exceptional circumstances test has been undertaken, as set out in the PPG (2a-010-20190220): “This will need to be assessed prior to, and separate from, considering how much of the overall need can be accommodated (and then translated into a housing requirement figure for the strategic policies in the plan).”[2] MHCLG: Planning Practice Guidance, Reference ID: 2a-010-20190220[3]MHCLG (August 2020): White Paper – Planning for the Future, paragraph 1.20