The Government’s latest retail sales figures show encouraging signs of recovery since lockdown, but what do the figures tell us about the future and the most likely “new norm”?

In the past consumer expenditure has grown consistently in real terms (over and above inflation) over the long term. This growth has fuelled the demand for new retail floorspace. Average retail expenditure per person in the UK grew by about 16% between 2009 to 2018 (Experian), despite the impact of the last recession i.e. 1.8% decline between 2009 and 2012. However, beyond this headline growth, home shopping accounts for much of this growth rather than in-store shopping. Expenditure growth per person attracted to traditional bricks and mortar retail was only 5% between 2009 to 2018, as a result demand for new retail floorspace has been sluggish during the last decade.

The short-term impact of the COVID-19 crisis is becoming clearer but the longer term structural implications are harder to predict. In the short term, operators have faced cash flow issues and increased costs arising from a slump in consumer demand and disruption to supply chains. Non-essential products, hospitality and leisure services have been hardest hit. Some retailers able to fulfil on-line orders/home delivery are benefiting at least in the short term from enforced changes in habits. There is likely to be a longer term structural shift to on-line shopping, reducing the demand for physical space within town centres. Following the COVID-19 furlough arrangements there is likely to be a spike in vacancies and some centres may struggle to fully recover. Some centres will need to explore opportunities beyond retail.

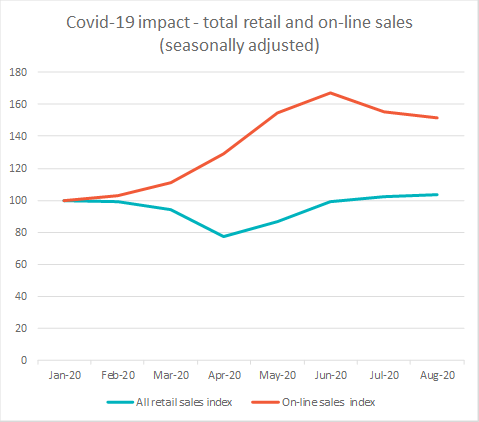

Office of National Statistic (ONS) monthly sales volume information for Great Britain indicates total retail sales volumes had recovered to previous levels of growth but the proportion of retail sales spent on-line is likely to represent a higher proportion of total sales, which will have an impact of traditional bricks and mortar retailing.

Retail sales volume fell by 22% in April 2020 during the start of lockdown. However, post lockdown sales during July and August recovered to pre-lockdown levels, with the August figure now 4% higher than the February figure. During lockdown on-line retail sales peaked in June at over 62% higher than pre-lockdown levels. On-line sales remain high at about 50% above normal levels.

Excluding on-line sales, the latest sales figures suggest bricks and mortar retail trade is still 6% down on pre-lockdown levels. This 6% reduction may not fully reflect the implications of the expected economic downturn, particularly after the furlough period ends in October. A challenging period for town centres and some operators over the next 3 to 5 years now seems likely, but these effects will not be evenly distributed.

The comparison goods (non-food) sector has been particularly affected with a 50% drop in sales from February to April, whilst the food sector experienced 10% growth in sales during March, in part due to panic buying at the start of the crisis. Food sales volumes have been consistently higher since February, benefiting from reduced trade in restaurants, cafés, pubs and bars.

The year to date sales figures (January to August) are down by -4.8%. Food stores achieved +4.4% growth compared with -18.2% reduction for non-food retail, with clothing and footwear the hardest hit at -30.1%. The continuation of these trends suggest higher order fashion shopping destinations could suffer most from the surge in on-line shopping. Lower order centres focusing on day-to-day essential items and services have, and should continue to recover more quickly.

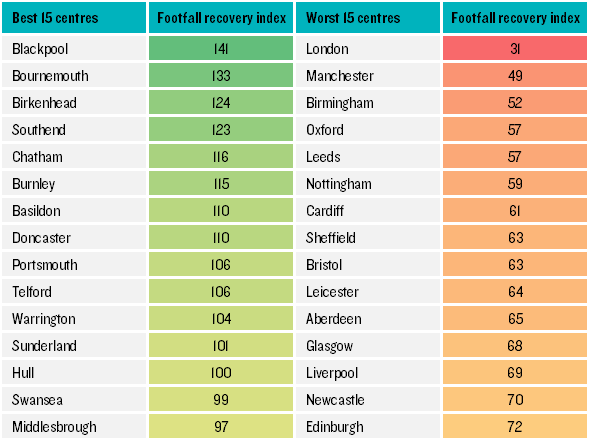

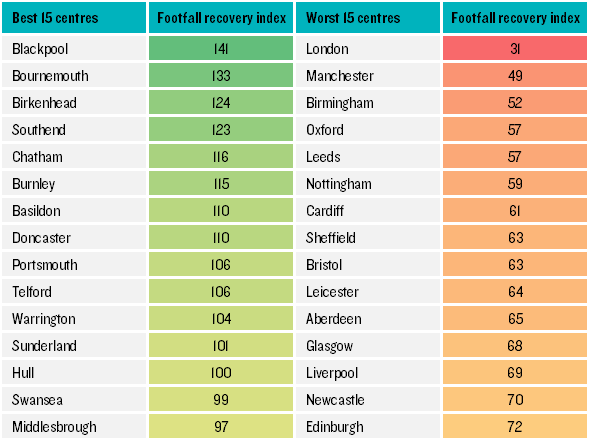

This trend is evident from the Centres for the Cities’ high street recovery tracker which monitors footfall and spend across cities and large towns. Large city centres have been slow to recover with many centres still 30% or more down on footfall and spend during the last week of August compared with pre-lockdown levels. The worst affected city centres in terms of footfall include: London (-69%), Manchester (-51%), Birmingham (-48%), Leeds (-43%) and Nottingham (-41%). These large centres have been the hardest hit due to increased home working and loss of international tourism. As a consequence of increased working from home, these headline figures for larger cities mask increased footfall within many local, district and town centres: which have seen a resurgence in footfall as people work and spend locally. Many satellite towns and seaside resorts have benefitted from home working, staycations and more customers shopping locally. The best performing towns include: Blackpool (+41%), Bournemouth (+33%), Birkenhead (+24%), Southend (+16%) and Chatham (+15%). This is likely due to the differing roles that high streets have in smaller towns. Where footfall has previously been driven by destination retail (for example the Bull ring in Birmingham or Oxford Street in London) or by office generated footfall, for example Leeds or the City of London, high streets have lost their customers during lockdown and the shift to working from home. In smaller towns, and local centres however there is evidence of customers returning, following the eat out to help out scheme and the benefits of being able to shop locally.

Source: Centres for Cities footfall data for 13 February – 1 September 2020

Some rebalancing from large to smaller centres will be welcomed in many areas, following the extended period of polarisation towards the most successful regional shopping destinations. This rebalancing could be sustained if, for example, increased home working continues. Town centres ability to retain market share and compete with on-line sales will be critical for the vitality and viability of town centres in the post-COVIDnorm. Town centres will need a coherent recovery strategy to have the best prospects of flourishing. Continued repurposing of retail space is inevitable due to the likely spike in vacancy rates and recent changes to the Use Class Order allowing more flexibility for changes of use.

Other blogs in this series: