There’s no doubt that Rishi Sunak’s relatively short tenure at No 11 Downing Street has been a challenge. At the time of

Budget 2020 (remember that?) in March last year, Sunak had been in the job for just three weeks – and within three of weeks of delivering his statement, the full impact of COVID-19 started to unfold as the country entered lockdown.

The ensuing recession – the deepest in the UK for 300 years – means we’ve heard much more regularly from the Chancellor over the past 12 months than might typically be the case, as various phases of the government’s support package have been rolled out, and then rolled out again, under the promise of “whatever it takes”.

But the resulting paradigm shift in the fiscal landscape can perhaps most easily be summed up as follows: in March 2020, the Chancellor set aside £12bn to provide support for public services, individuals and businesses whose finances have been affected by COVID-19; the actual cost so far has been around £280bn. Beyond the numbers, the pandemic has, naturally, also stalled much of the government’s wider economic policy agenda, such as the manifesto commitment to “levelling up” areas across the country. Many earlier announcements, such as the planned Comprehensive Spending Review, have also been pared back.

So it was against this backdrop that the Chancellor delivered his second

Budget this week, which he summed up as a

“moment of challenge and of change”. It had been widely trailed that the government would pursue a ‘spend now…but pay later’ approach when faced with the highest level of public borrowing since the Second World War; the effect of the further COVID-19 support measures announced will take the total bill to £407bn.

The Chancellor is taking a calculated risk that the economy will be on the mend and growing again at the point that various new tax rise measures start to bite over the next few years. In this respect, the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) brought some good news in their latest

outlook – GDP is now expected to grow by 4% in 2021 and to reach its pre-pandemic level by mid-2022, six months earlier than had previously been expected. The OBR warned, however, that they expect the economy to be 3% smaller in the medium term compared to its pre-COVID path – in part due to recent falls in net migration.

But the Chancellor wants more than an economic recovery that is set to autopilot, stating: “it’s not enough to have some general desire to grow the economy…we need a real commitment to create jobs where people are and change the economic geography of this country.” The tone was set for change, including addressing the challenges of long-term green growth and levelling-up. On the latter, Rishi Sunak is starting close to home – by confirming the move of 750 HM Treasury officials to Darlington as part of the “Treasury North” campus.

The Budget was accompanied by the publication of

Build Back Better: our plan for growth, a policy paper which sets out the government’s plans to support economic growth through investment in infrastructure, skills and innovation – it effectively provides a new framework that supersedes the

2017 Industrial Strategy as the central policy reference point. This paper also details a series of new funding arrangements, and confirmed that the long-awaited UK Shared Prosperity Fund will arrive in 2022 to replace European Union structural funds as they expire after 2022-23.

More immediately, government launched a new

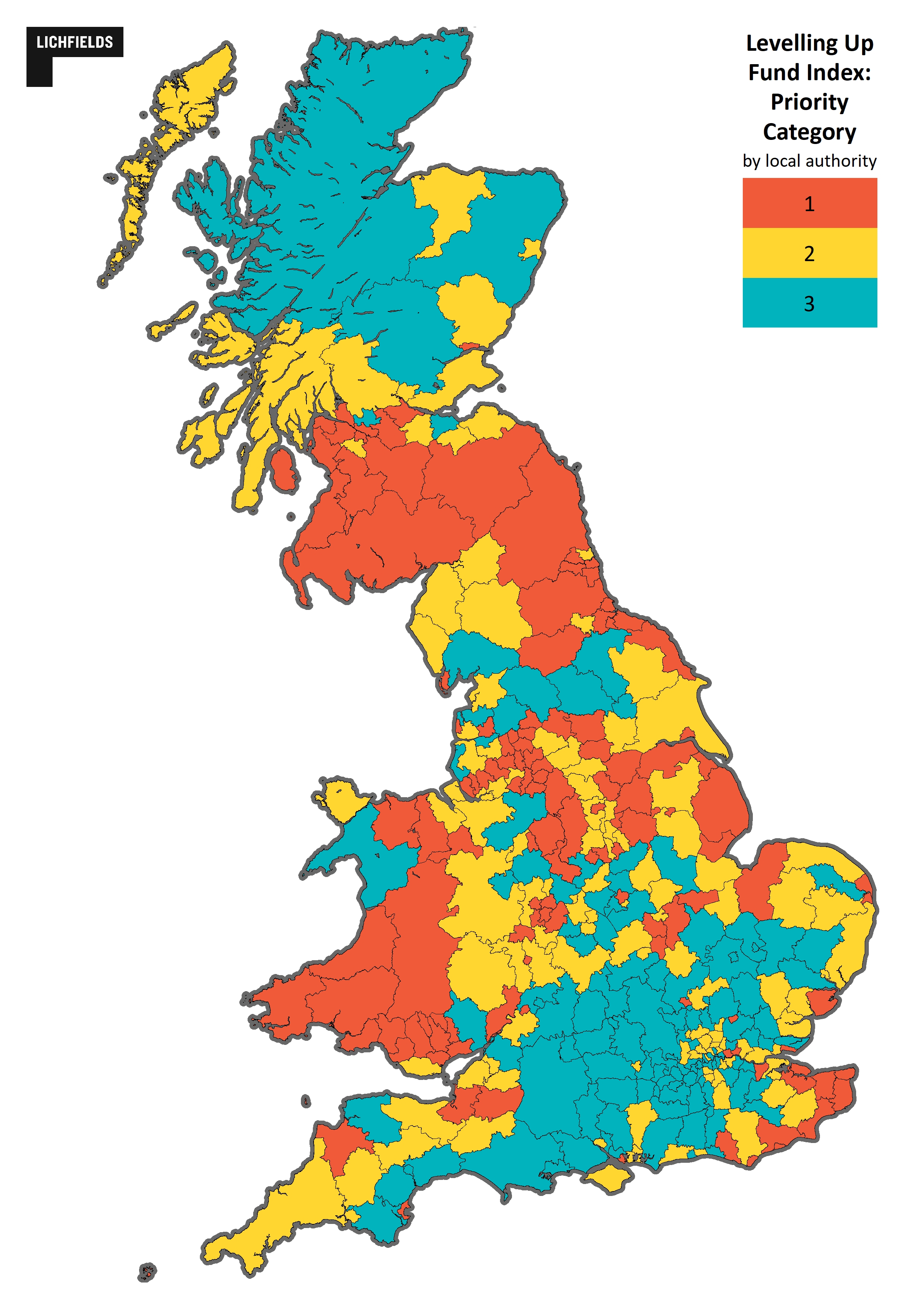

Levelling Up Fund worth £4.8bn until 2024-25, with a first round focused on local transport projects, town centre regeneration, and culture and heritage – the deadline for competitive submissions by local authorities is 18 June 2021. For this purpose, every local authority in the country has been placed into one of

three levels of priority group – as shown on the map below – with preference to be given to bids from higher priority areas based on their need for economic recovery and growth, need for improved transport connectivity and need for regeneration. The exact details of how government arrived at this prioritisation have not yet been released, and a number of criticisms have already been levelled at some of the categorisation reported in the media. Potential candidate projects for funding are expected to align with relevant Local Plans, Local Industrial Strategies or Local Transport Plans.

Other key announcements included:

- the creation of the first ever UK Infrastructure Bank to be headquartered in Leeds that will focus (at least initially) on investments to tackle climate change and support regional economic growth, and that will have a degree of operational independence from government;

- the latest round of confirmed Town Deal settlements for 45 towns nationally;

- the designation of eight Freeport locations[1] across the country which will be eligible for tax incentives to attract investment, easier customs processes and simplified planning measures;

- the terms of reference for a new study from the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) on how to maximise the benefits of infrastructure policy and investment for towns – with an emphasis on transport and digital – to report by September 2021; and

- a signal that there could be further change on the way for Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), as government indicated it would be looking at the future role of LEPs, including their geographies, over the coming months and will announce more detailed plans ahead of the summer recess.

Ultimately, this was a Budget very much defined by the long shadow of the pandemic on the state of the public finances, even at this moment when there is more confidence about the way ahead and an economy that can start to grow again. But it was also about the Chancellor attempting to kick start the government’s longer-term economic policy programme and delivering against its political commitments.

[1] East Midlands Airport, Felixstowe and Harwich, Humber, Liverpool City Region, Plymouth, Solent, Thames, Teesside.

Image credit: @rishisunakmp via Instagram