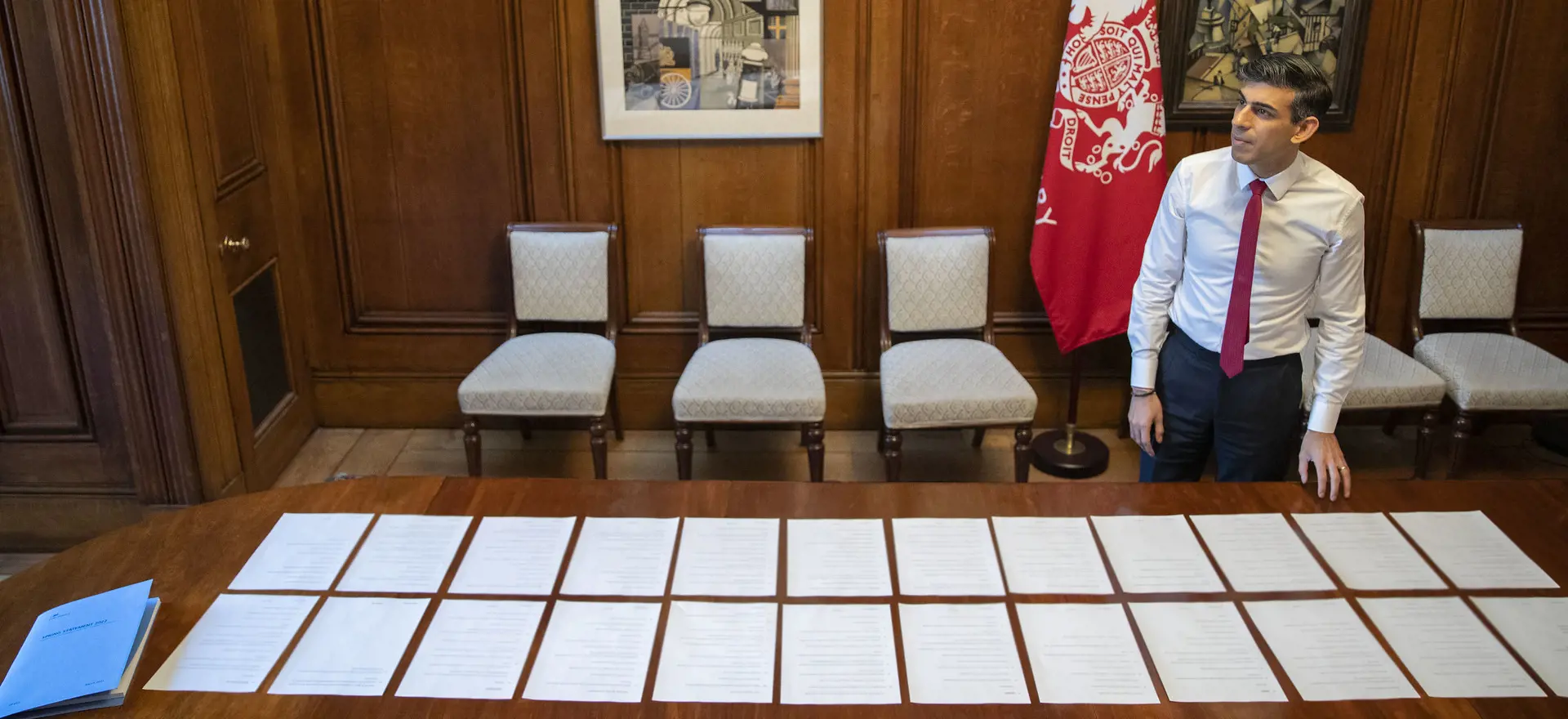

As Rishi Sunak presided over today’s Spring Statement, the government’s last fiscal event – the

Autumn Budget and Spending Review – felt like something not just from a different season, but a different era.

Much has clearly changed in the six months since last October; first, the Omicron variant prolonged the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic over the winter, and second, the war in Ukraine has created humanitarian and geo-political impacts with far-reaching economic consequences without parallel in recent times. The combined effect of these is borne out by the latest figures which show that the UK economy contracted again (briefly) in December 2021 as the Plan B restrictions weighed down on activity, and

forecasts published today by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) were revised down from 4.9% to 3.9% for 2022, and slowing further to 1.8% in 2023 as the post-pandemic ‘bounce back’ fades.

Notwithstanding these factors, so far business confidence has generally held up well and the labour market remains buoyant. Better weather, longer days and the absence of Covid restrictions also give reasons for optimism. Consumer sentiment is, however, showing some signs of faltering in response to the squeeze on real household disposable incomes, and there’s a widespread expectation that the housing market – so often a barometer for the wider economy as a whole – will cool off as the year progresses.

Inflation driven by rising prices for global energy and tradable goods (and the UK being a net importer of both) will create strong headwinds for the foreseeable future, and even the Bank of England recently

conceded there is little that monetary policy can do about this in the short term at least. There’s been some relative improvement in the public finances, but civil servants at HM Treasury know that fortunes can change quickly and servicing government debt is becoming more expensive.

So with things finally balanced, in recent weeks the Treasury’s official position has been that the

Spring Statement would be unapologetically

“policy light”. At the same time, Sunak has been busy managing expectations by reminding us that government spending alone can’t provide for all eventualities. But it was inevitable that demands would be made for the Chancellor to help cushion the impending cost of living crisis and to help bolster the economy in uncertain times – to which he responded with immediate measures announced to temporarily cut fuel duty, raise National Insurance thresholds from July, introducing zero VAT ratings for some energy efficiency measures and an increase in the Employment Allowance, amongst others. Finally, Sunak wanted to deliver on his political conviction to be seen as a tax-cutting chancellor by announcing a cut to the basic rate of income tax from 20% to 19% from April 2024. However, what savings all these measures will deliver for households in real terms remains to be seen, and the OBR has concluded that the net effect will still see an increase in taxes in the long-run.

It wasn’t particularly the time or backdrop to headline any new policy decisions on planning, housing or regional growth measures. There was, however, a re-statement of the government’s priorities to promote economic growth and increase living standards. These comprise tackling some of the fundamentals that have held back productivity levels:

- Capital — cutting and reforming taxes on business investment to encourage firms to invest in productivity-enhancing assets.

- People — encouraging businesses to offer more high-quality employee training and exploring whether the current tax system – including the operation of the Apprenticeship Levy – is doing enough to incentivise businesses to invest in the right kinds of training.

- Ideas — delivering increased public investment in R&D and doing more through the tax system to encourage greater private sector investment in R&D.

A broader question is where this now positions the government’s

“levelling up” agenda following the

White Paper published last month. With progress having been stalled by the pandemic, it is firmly set as a flagship policy across Whitehall and government wants to make a visible down payment on its promises to voters ahead of the next general election. While the Spring Statement confirmed the launch of the second round of the Levelling Up Fund (£4.8 billion for local infrastructure projects, of which £1.7 billion has already been allocated), there remains no extra spending available over and above what had already been set out in the Autumn Budget.

In an

interview to coincide with the conclusion of his six-month tenure as head of the government’s levelling up task force, Andy Haldane acknowledged that the impact of the rising living costs we are now seeing will fall disproportionately on those in the

“left behind” areas that the policy agenda is intended to help the most. But he remained clear that while achieving the 12 levelling up

“missions” will now be harder, particularly by 2030 as intended, it arguably makes the very rationale for delivering on the missions themselves even more important.

These missions will soon become enshrined in legislation, holding government to account on monitoring and delivering progress in the future. So while levelling up policy is not just confined to matters of more public spending – which must work in tandem with devolution of powers to local areas and other reforms – one suspects that this is something that future budgets and spending reviews will need to return to.

Image credit: @RishiSunak on Twitter